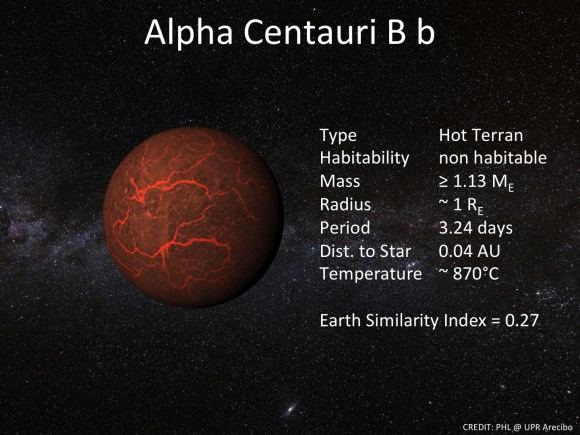

Following last Friday’s press release from the International Astronomical Union (IAU) concerning the naming of extrasolar planets, a heated debate has arisen over two separate but related issues. One is the “official” vs. “popular” names of astronomical objects (and the IAU’s jurisdiction over them) and the other is Uwingu’s intentions in their exoplanet naming contests.

We’re going to talk about the latter first, as this seems to be where much of the contention lies.

As has been reflected in our articles, Universe Today feels that Uwingu has always been upfront that the names chosen in their exoplanet naming contests were never meant to be “officially” recognized by the IAU, but instead are a way to engage the public and to create non-governmental funding for space research. As we said in our article on Nov. 7, 2012 about the first contest that creates a “baby book” of exoplanet names:

The names won’t be officially approved by the International Astronomical Union, but (Alan) Stern said they will be are similar to the names given to features on Mars by the mission science teams (such as the “Jake Matijevic” rock recently analyzed by the Curiosity rover) that everyone ends up using. This also solves the problem of how to come up with names, a task that the IAU has yet to discuss.

Please read these articles on Time and New Scientist which explicitly quote Uwingu CEO Alan Stern as saying the names generated by Uwingu’s contest will not be officially recognized by the IAU, but are a way to get the public involved and excited about exoplanets.

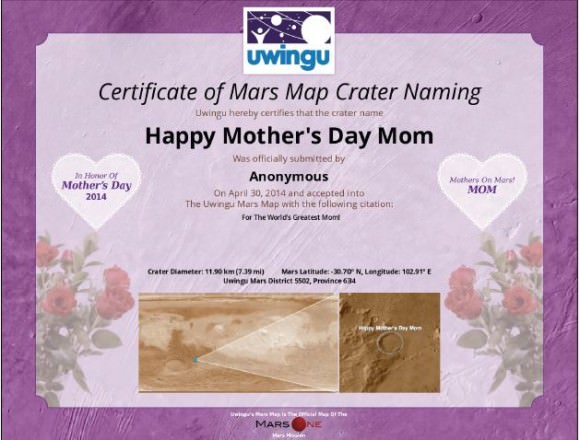

Anyone who implies that Uwingu is like the ‘name a star’ scams, or that they are out to make money to line their own pockets is completely misreading Uwingu’s website and completely missing the point. The profits go towards science research and education. So far Uwingu has given approximately $5,500 to several projects: Astronomers Without Borders, the Galileo Teacher Training Program, the Purdue Multiethnic Training Program, and the Allen Telescope Array for SETI.

Additionally, as the Uwingu Twitter feed confirmed, “No one at Uwingu has ever been paid, we have all worked for free from the start.”

The IAU’s statement on Friday infers that Uwingu is trying to sell “the rights to name exoplanets” and today Uwingu issued a statement that says the IAU’s press release “significantly mischaracterized Uwingu’s People’s Choice contest and Uwingu itself.”

As astronomer Carolyn Collins Petersen wrote on her Spacewriter’s Ramblings blog, nowhere on Uwingu’s website does it say that you’re buying the right to name a planet, as seems to be suggested by the IAU press release.

“If you donate a few dollars, you get to suggest a name,” she wrote. “You donate a few cents and you can vote for the coolest names. The coolest names win prizes. The money goes to research and education.”

And Stern has said the time has come where exoplanets should be named: “The IAU has had ten years to do something about this and they haven’t done anything,” he told Universe Today previously. “What we’re doing might be controversial, but that’s OK. It’s time to step up to the plate and do something.”

And many agree with his point that since the public is obviuosly intrigued and interested in exoplanets, they should be involved in the naming process, if only to suggest names. And as we’ve said before, since the IAU has said it will be difficult to come up with names since there are now hundreds of known explanets, Uwingu’s projects fits the bill of what is needed.

Also from Uwingu’s statement today:

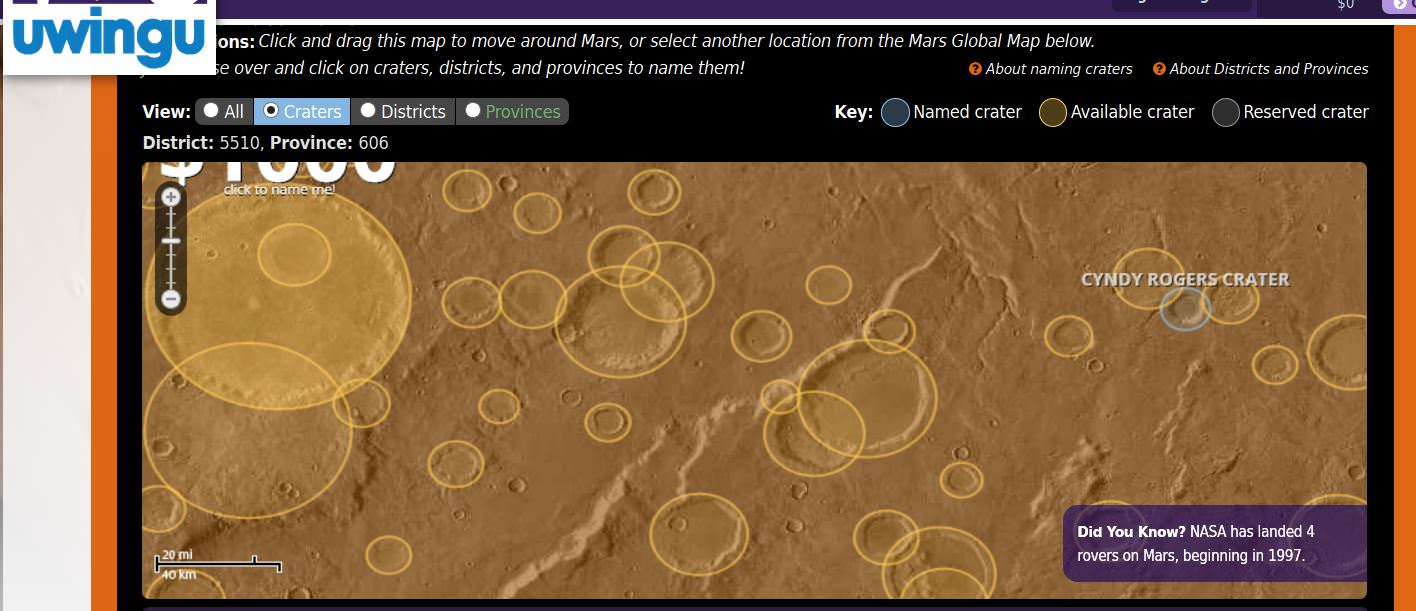

Uwingu affirms the IAU’s right to create naming systems for astronomers. But we know that the IAU has no purview — informal or official — to control popular naming of bodies in the sky or features on them, just as geographers have no purview to control people’s naming of features along hiking trails. People clearly enjoy connecting to the sky and having an input to common-use naming. We will continue to stand up for the public’s rights in this regard, and look forward to raising more grant funds for space researchers and educators this way.

Over the weekend, the debate raged on the various social media outlets, and astronomer Jason Wright wrote a blog post that called out the IAU’s statement, saying it couldn’t be the official IAU policy, because “IAU policy is determined by democratic vote of its commissions and General Assembly. Neither has endorsed any nomenclature for planets, much less the assertions of the press release.”

Wright added that he contacted a member of Commission 53 (the IAU committee that will discuss the future of exoplanet naming) “and learned that they were not consulted for or even informed of this press release before it went out, and that the commission has not established a naming process since it met in Beijing in 2012.”

As far as the difference between “official” and “common” names, the IAU said in their press release that a “clear and systematic system for naming these objects is vital. Any naming system is a scientific issue that must also work across different languages and cultures in order to support collaborative worldwide research and avoid confusion.”

However, many people have pointed out that other sciences — like biology – have scientific names and common names that are both used and there doesn’t appear to be rampant confusion over this.

But stars can have several names as well, as astronomer Stuart Lowe wrote in his Astroblog, “Currently stars can have one proper name but also be in many different catalogues with different IDs.”

Uwingu pointed out in their statement that the star Polaris (its well-known common name!) is also known as the North Star, Alpha Ursae Minoris, HD 8890, HIP 11767, SAO 308, ADS 1477, FK5 907, and over a dozen more designations.

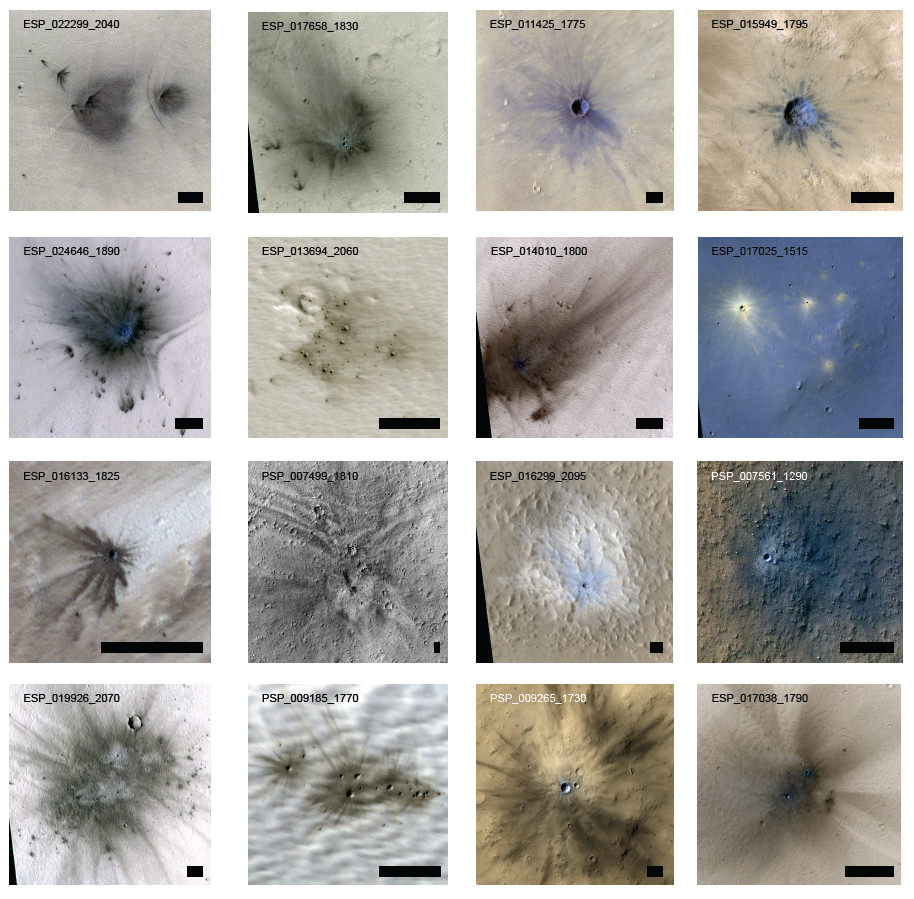

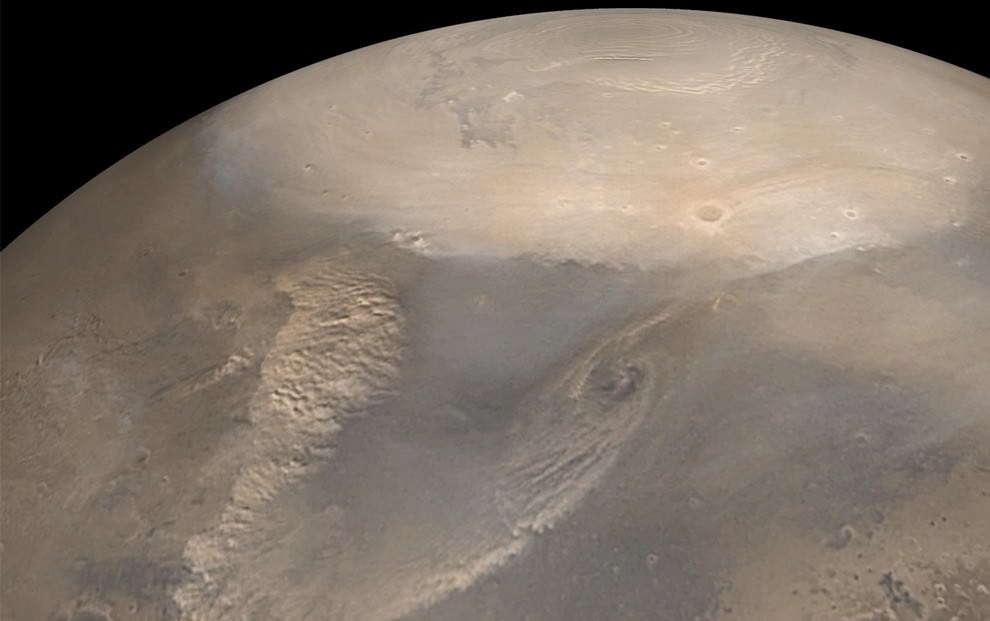

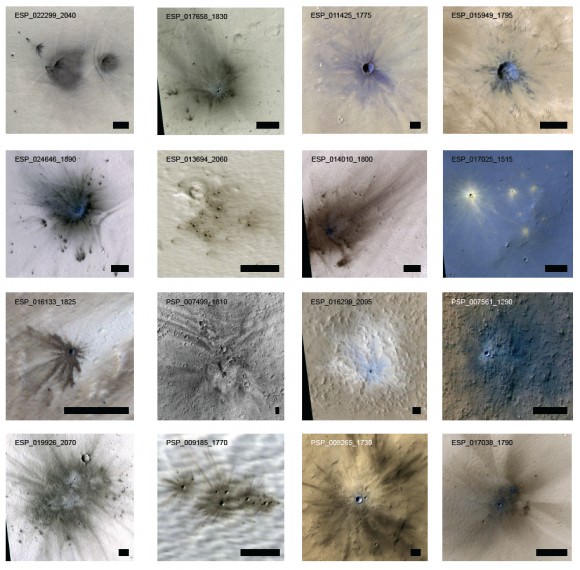

Uwingu also noted how non-scientific, informal names are prevalent in astronomy. Our own Milky Way galaxy is a great example, and “there are many instances where astronomers name things without going through the IAU’s internal process. There are many of features on Mars, ranging from mountains to individual rocks, with names applied by Mars-mission scientists and never adopted by, or even considered by, the IAU. And Apollo astronauts did not seek IAU permission before naming features at their landing sites or from orbit.”

Also, recent press releases reflect where astronomical objects were given names by astronomers without any IAU process such as Supernova Wilson, Galaxy cluster “El Gordo,” and the “Black Eye Galaxy.” “None drew attention from the IAU,” Uwingu said.

Planetary scientist and educator David Grinspoon (who is on Uwingu’s board of advisors) probably summed it up best in a comment he posted on Universe Today: “IAU maintains names for astronomers and that’s fine, but they do not own the sky. Planets are PLACES not just astronomical research objects, and if informal names for these places proliferate, outside of some self-appointed professional “authority”, and the public at large is more engaged in the exoplanet revolution, that is a very good thing indeed.”