Perhaps the most important question we can possible ask is, “are we alone in the Universe?”.

And so far, the answer has been, “I don’t know”. I mean, it’s a huge Universe, with hundreds of billions of stars in the Milky Way, and now we learn there are trillions of galaxies in the Universe.

Is there life closer to home? What about in the Solar System? There are a few existing places we could look for life close to home. Really any place in the Solar System where there’s liquid water. Wherever we find water on Earth, we find life, so it make sense to search for places with liquid water in the Solar System.

I know, I know, life could take all kinds of wonderful forms. Enlightened beings of pure energy, living among us right now. Or maybe space whales on Titan that swim through lakes of ammonia. Beep boop silicon robot lifeforms that calculate the wasted potential of our lives.

Sure, we could search for those things, and we will. Later. We haven’t even got this basic problem done yet. Earth water life? Check! Other water life? No idea.

It turns out, water’s everywhere in the Solar System. In comets and asteroids, on the icy moons of Jupiter and Saturn, especially Europa or Enceladus. Or you could look for life on Mars.

Mars is similar to Earth in many ways, however, it’s smaller, has less gravity, a thinner atmosphere. And unfortunately, it’s bone dry. There are vast polar caps of water ice, but they’re frozen solid. There appears to be briny liquid water underneath the surface, and it occasionally spurts out onto the surface. Because it’s close and relatively easy to explore, it’s been the place scientists have gone looking for past or current life.

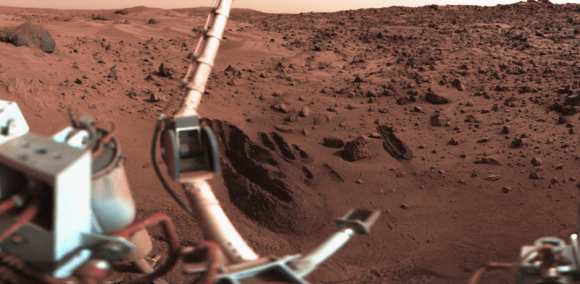

Researchers tried to answer the question with NASA’s twin Viking Landers, which touched down in 1976. The landers were both equipped with three biology experiments. The researchers weren’t kidding around, they were going to nail this question: is there life on Mars?

In the first experiment, they took soil samples from Mars, mixed in a liquid solution with organic and inorganic compounds, and then measured what chemicals were released. In a second experiment, they put Earth organic compounds into Martian soil, and saw carbon dioxide released. In the third experiment, they heated Martian soil and saw organic material come out of the soil.

Three experiments, and stuff happened in all three. Stuff! Pretty exciting, right? Unfortunately, there were equally plausible non-biological explanations for each of the results. The astrobiology community wasn’t convinced, and they still fight in brutal cage matches to this day. It was ambitious, but inconclusive. The worst kind of conclusive.

Researchers found more inconclusive evidence in 1994. Ugh, there’s that word again. They were studying a meteorite that fell in Antarctica, but came from Mars, based on gas samples taken from inside the rock.

They thought they found evidence of fossilized bacterial life inside the meteorite. But again, there were too many explanations for how the life could have gotten in there from here on Earth. Life found a way… to burrow into a rock from Mars.

NASA learned a powerful lesson from this experience. If they were going to prove life on Mars, they had to go about it carefully and conclusively, building up evidence that had no controversy.

The Spirit and Opportunity Rovers were an example of building up this case cautiously. They were sent to Mars in 2004 to find evidence of water. Not water today, but water in the ancient past. Old water Over the course of several years of exploration, both rovers turned up multiple lines of evidence there was water on the surface of Mars in the ancient past.

They found concretions, tiny pebbles containing iron-rich hematite that forms on Earth in water. They found the mineral gypsum; again, something that’s deposited by water on Earth.

NASA’s Curiosity Rover took this analysis to the next level, arriving in 2012 and searching for evidence that water was on Mars for vast periods of time; long enough for Martian life to evolve.

Once again, Curiosity found multiple lines of evidence that water acted on the surface of Mars. It found an ancient streambed near its landing site, and drilled into rock that showed the region was habitable for long periods of time.

In 2014, NASA turned the focus of its rovers from looking for evidence of water to searching for past evidence of life.

Curiosity found one of the most interesting targets: a strange strange rock formations while it was passing through an ancient riverbed on Mars. While it was examining the Gillespie Lake outcrop in Yellowknife Bay, it photographed sedimentary rock that looks very similar to deposits we see here on Earth. They’re caused by the fossilized mats of bacteria colonies that lived billions of years ago.

Not life today, but life when Mars was warmer and wetter. Still, fossilized life on Mars is better than no life at all. But there might still be life on Mars, right now, today. The best evidence is not on its surface, but in its atmosphere. Several spacecraft have detected trace amounts of methane in the Martian atmosphere.

Methane is a chemical that breaks down quickly in sunlight. If you farted on Mars, the methane from your farts would dissipate in a few hundred years. If spacecraft have detected this methane in the atmosphere, that means there’s some source replenishing those sneaky squeakers. It could be volcanic activity, but it might also be life. There could be microbes hanging on, in the last few places with liquid water, producing methane as a byproduct.

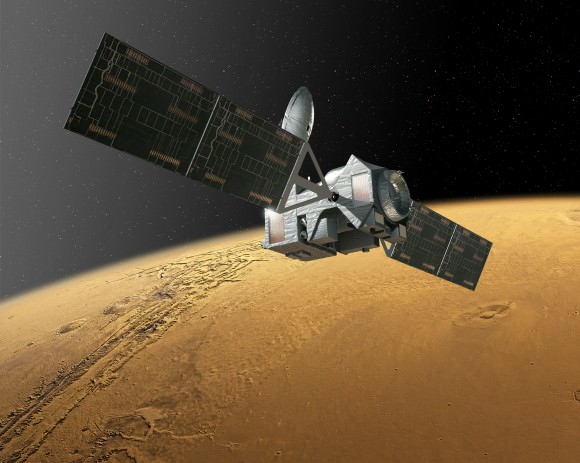

The European ExoMars orbiter just arrived at Mars, and its main job is sniff the Martian atmosphere and get to the bottom of this question.

Are there trace elements mixed in with the methane that means its volcanic in origin? Or did life create it? And if there’s life, where is it located? ExoMars should help us target a location for future study.

NASA is following up Curiosity with a twin rover designed to search for life. The Mars 2020 Rover will be a mobile astrobiology laboratory, capable of scooping up material from the surface of Mars and digesting it, scientifically speaking. It’ll search for the chemicals and structures produced by past life on Mars. It’ll also collect samples for a future sample return mission.

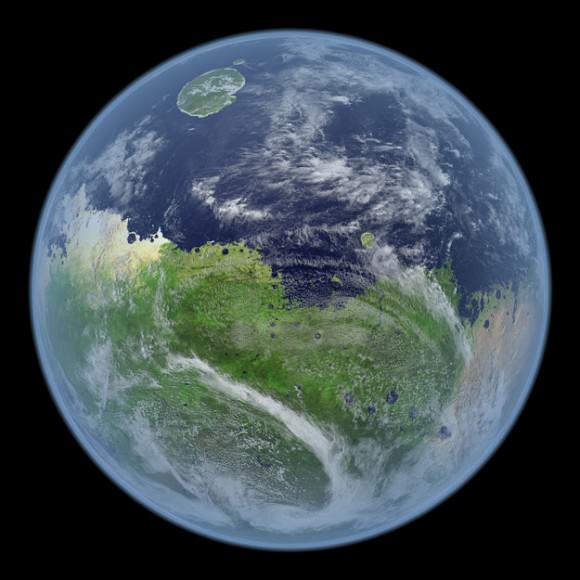

Even if we do discover if there’s life on Mars, it’s entirely possible that we and Martian life are actually related by a common ancestor, that split off billions of years ago. In fact, some astrobiologists think that Mars is a better place for life to have gotten started.

Not the dry husk of a Red Planet that we know today, but a much wetter, warmer version that we now know existed billions of years ago. When the surface of Mars was warm enough for liquid water to form oceans, lakes and rivers. And we now know it was like this for millions of years.

While Earth was still reeling from an early impact by the massive planet that crashed into it, forming the Moon, life on Mars could have gotten started early.

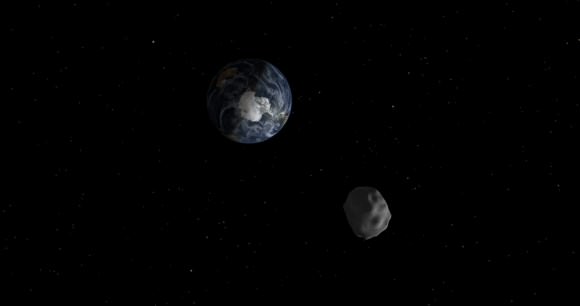

But how could we actually be related? The idea of Panspermia says that life could travel naturally from world to world in the Solar System, purely through the asteroid strikes that were regularly pounding everything in the early days.

Imagine an asteroid smashing into a world like Mars. In the lower gravity of Mars, debris from the impact could be launched into an escape trajectory, free to travel through the Solar System.

We know that bacteria can survive almost indefinitely, freeze dried, and protected from radiation within chunks of space rock. So it’s possible they could make the journey from Mars to Earth, crossing the orbit of our planet.

Even more amazingly, the meteorites that enter the Earth’s atmosphere would protect some of the bacterial inhabitants inside. As the Earth’s atmosphere is thick enough to slow down the descent of the space rocks, the tiny bacterialnauts could survive the entire journey from Mars, through space, to Earth.

If we do find life on Mars, how will we know it’s actually related to us? If Martian life has the similar DNA structure to Earth life, it’s probably related. In fact, we could probably trace the life back to determine the common ancestor, and even figure out when the tiny lifeforms make the journey.

If we do find life on Mars, which is related to us, that just means that life got around the Solar System. It doesn’t help us answer the bigger question about whether there’s life in the larger Universe. In fact, until we actually get a probe out to nearby stars, or receive signals from them, we might never know.

An even more amazing possibility is that it’s not related. That life on Mars arose completely independently. One clue that scientists will be looking for is the way the Martian life’s instructions are encoded. Here on Earth, all life follows “left-handed chirality” for the amino acid building blocks that make up DNA and RNA. But if right-handed amino acids are being used by Martian life, that would mean a completely independent origin of life.

Of course, if the life doesn’t use amino acids or DNA at all, then all bets are off. It’ll be truly alien, using a chemistry that we don’t understand at all.

There are many who believe that Mars isn’t the best place in the Solar System to search for life, that there are other places, like Europa or Enceladus, where there’s a vast amount of liquid water to be explored.

But Mars is close, it’s got a surface you can land on. We know there’s liquid water beneath the surface, and there was water there for a long time in the past. We’ve got the rovers, orbiters and landers on the planet and in the works to get to the bottom of this question. It’s an exciting time to be part of this search.