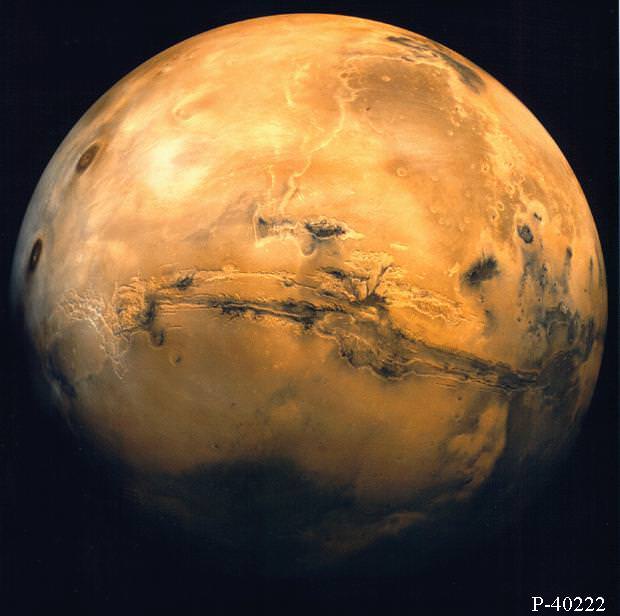

Mars is not exactly a friendly place for life as we know it. While temperatures at the equator can reach as high as a balmy 35 °C (95 °F) in the summer at midday, the average temperature on the surface is -63 °C (-82 °F), and can reach as low as -143 °C (-226 °F) during winter in the polar regions. Its atmospheric pressure is about one-half of one percent of Earth’s, and the surface is exposed to a considerable amount of radiation.

Until now, no one was certain if microorganisms could survive in this extreme environment. But thanks to a new study by a team of researchers from the Lomonosov Moscow State University (LMSU), we may now be able to place constraints on what kinds of conditions microorganisms can withstand. This study could therefore have significant implications in the hunt for life elsewhere in the Solar System, and maybe even beyond!

The study, titled “100 kGy gamma-affected microbial communities within the ancient Arctic permafrost under simulated Martian conditions“, recently appeared in the scientific journal Extremophiles. The research team, which was led by Vladimir S. Cheptsov of LMSU, included members from the Russian Academy of Sciences, St. Petersburg State Polytechnical University, the Kurchatov Institute and Ural Federal University.

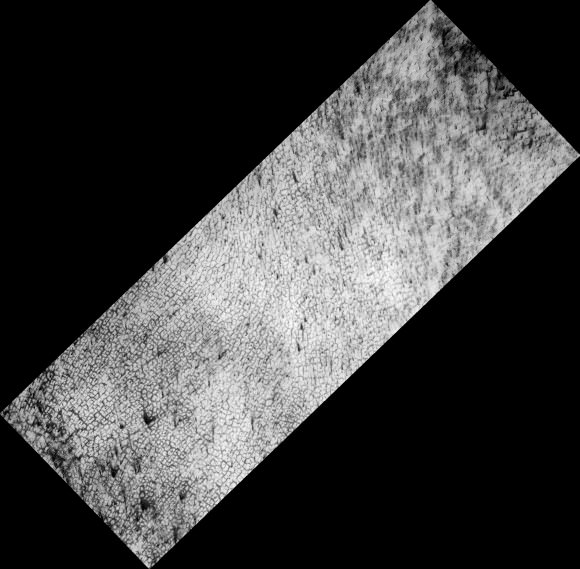

For the sake of their study, the research team hypothesized that temperature and pressure conditions would not be the mitigating factors, but rather radiation. As such, they conducted tests where microbial communities contained within simulated Martian regolith were then irradiated. The simulated regolith consisted of sedimentary rocks that contained permafrost, which were then subjected to low temperature and low pressure conditions.

As Vladimir S. Cheptsov, a post-graduate student at the Lomonosov MSU Department of Soil Biology and a co-author on the paper, explained in a LMSU press statement:

“We have studied the joint impact of a number of physical factors (gamma radiation, low pressure, low temperature) on the microbial communities within ancient Arctic permafrost. We also studied a unique nature-made object—the ancient permafrost that has not melted for about 2 million years. In a nutshell, we have conducted a simulation experiment that covered the conditions of cryo-conservation in Martian regolith. It is also important that in this paper, we studied the effect of high doses (100 kGy) of gamma radiation on prokaryotes’ vitality, while in previous studies no living prokaryotes were ever found after doses higher than 80 kGy.”

To simulate Martian conditions, the team used an original constant climate chamber, which maintained the low temperature and atmospheric pressure. They then exposed the microorganisms to varying levels of gamma radiation. What they found was that the microbial communities showed high resistance to the temperature and pressure conditions in the simulated Martian environment.

However, after they began irradiating the microbes, they noticed several differences between the irradiated sample and the control sample. Whereas the total count of prokaryotic cells and the number of metabolically active bacterial cells remained consistent with control levels, the number of irradiated bacteria decreased by two orders of magnitude while the number of metabolically active cells of archaea also decreased threefold.

The team also noticed that within the exposed sample of permafrost, there was a high biodiversity of bacteria, and this bacteria underwent a significant structural change after it was irradiated. For instance, populations of actinobacteria like Arthrobacter – a common genus found in soil – were not present in the control samples, but became predominant in the bacterial communities that were exposed.

In short, these results indicated that microorganisms on Mars are more survivable than previously thought. In addition to being able to survive the cold temperatures and low atmospheric pressure, they are also capable of surviving the kinds of radiation conditions that are common on the surface. As Cheptsov explained:

“The results of the study indicate the possibility of prolonged cryo-conservation of viable microorganisms in the Martian regolith. The intensity of ionizing radiation on the surface of Mars is 0.05-0.076 Gy/year and decreases with depth. Taking into account the intensity of radiation in the Mars regolith, the data obtained makes it possible to assume that hypothetical Mars ecosystems could be conserved in an anabiotic state in the surface layer of regolith (protected from UV rays) for at least 1.3 million years, at a depth of two meters for no less than 3.3 million years, and at a depth of five meters for at least 20 million years. The data obtained can also be applied to assess the possibility of detecting viable microorganisms on other objects of the solar system and within small bodies in outer space.”

This study was significant for multiple reasons. On the one hand, the authors were able to prove for the first time that prokaryote bacteria can survive radiation does in excess of 80 kGy – something which was previously thought to be impossible. They also demonstrated that despite its tough conditions, microorganisms could still be alive on Mars today, preserved in its permafrost and soil.

The study also demonstrates the importance of considering both extraterrestrial and cosmic factors when considering where and under what conditions living organisms can survive. Last, but not least, this study has done something no previous study has, which is define the limits of radiation resistance for microorganisms on Mars – specifically within regolith and at various depths.

This information will be invaluable for future missions to Mars and other locations in the Solar System, and perhaps even with the study of exoplanets. Knowing the kind of conditions in which life will thrive will help us to determine where to look for signs of it. And when preparing missions to other words, it will also let scientists know what locations to avoid so that contamination of indigenous ecosystems can be prevented.

Further Reading: Lomonsonov Moscow State University, Extremophiles