Just. Wow.

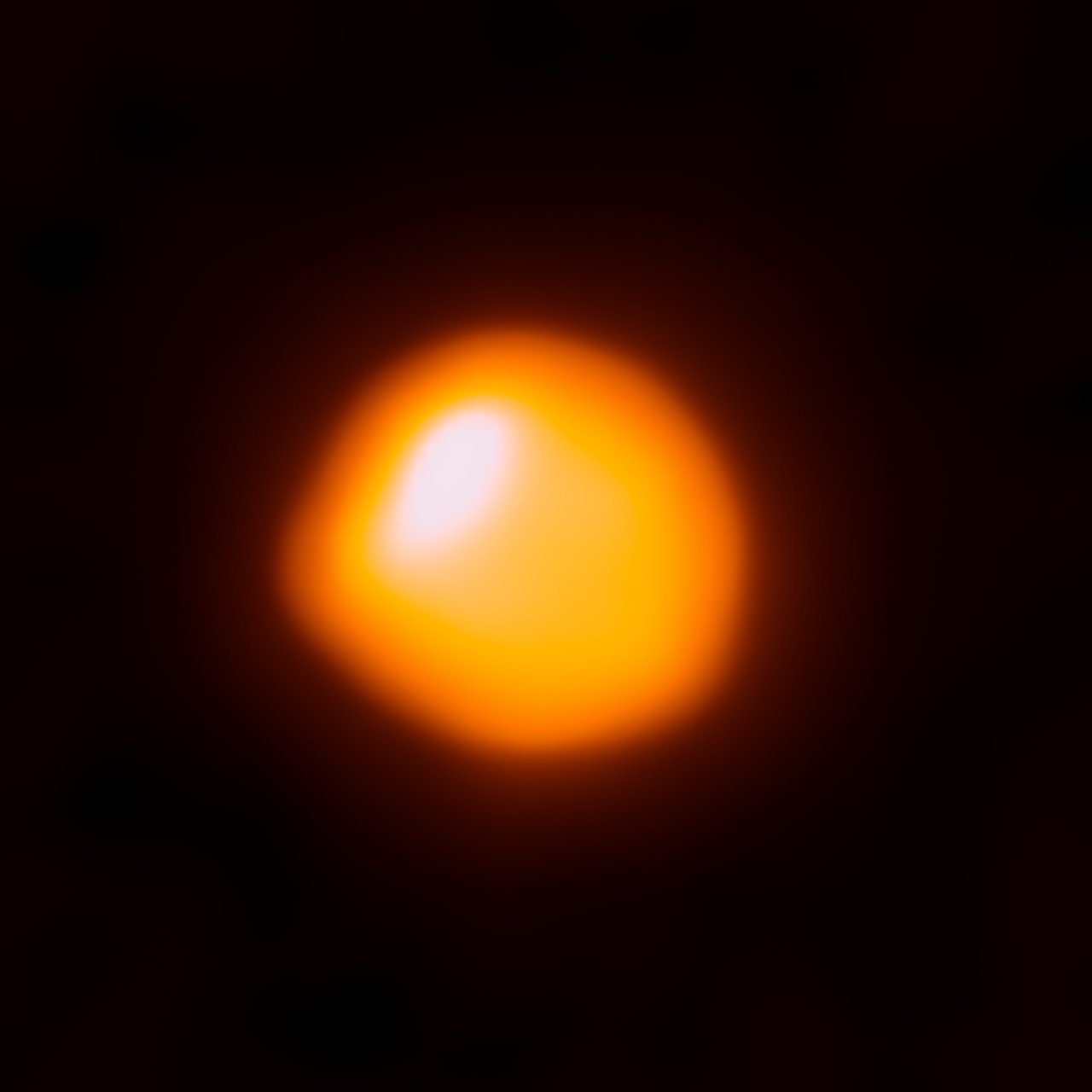

An angry monster lurks in the shoulder of the Hunter. We’re talking about the red giant star Betelgeuse, also known as Alpha Orionis in the constellation Orion. Recently, the Atacama Large Millimeter Array (ALMA) gave us an amazing view of Betelgeuse, one of the very few stars that is large enough to be resolved as anything more than a point of light.

Located 650 light years distant, Betelgeuse is destined to live fast, and die young. The star is only eight million years old – young as stars go. Consider, for instance, our own Sun, which has been shining as a Main Sequence star for more than 500 times longer at 4.6 billion years – and already, the star is destined to go supernova at anytime in the next few thousand years or so, again, in a cosmic blink of an eye.

An estimated 12 times as massive as Sol, Betelgeuse is perhaps a staggering 6 AU or half a billion miles in diameter; plop it down in the center of our solar system, and the star might extend out past the orbit of Jupiter.

As with many astronomical images, the wow factor comes from knowing just what you’re seeing. The orange blob in the image is the hot roiling chromosphere of Betelgeuse, as viewed via ALMA at sub-millimeter wavelengths. Though massive, the star only appears 50 milliarcseconds across as seen from the Earth. To give you some idea just how small a milliarcsecond is, there’s a thousand of them in an arc second, and 60 arc seconds in an arc minute. The average Full Moon is 30 arc minutes across, or 1.8 million milliarcseconds in apparent diameter. Betelgeuse has one of the largest apparent diameters of any star in our night sky, exceeded only by R Doradus at 57 milliarcseconds.

The apparent diameter of Betelgeuse was first measured by Albert Michelson using the Mount Wilson 100-inch in 1920, who obtained an initial value of 240 million miles in diameter, about half the present accepted value, not a bad first attempt.

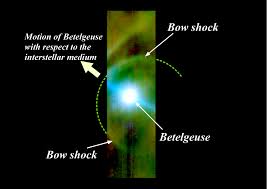

You can see hints of an asymmetrical bubble roiling across the surface of Betelgeuse in the ALMA image. Betelgeuse rotates once every 8.4 years. What’s going on under that uneasy surface? Infrared surveys show that the star is enveloped in an enormous bow-shock, a powder-keg of a star that will one day provide the Earth with an amazing light show.

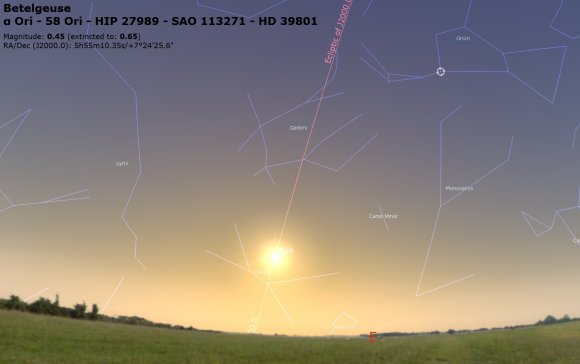

Thankfully, Betelgeuse is well out of the supernova “kill zone” of 25 to 100 light years (depending on the study). Along with Spica at 250 light years distant in the constellation Virgo, both are prime nearby supernovae candidates that will on day give astronomers a chance to study the anatomy of a supernova explosion up close. Riding high to the south in the northern hemisphere nighttime sky in the wintertime, +0.5 magnitude Betelgeuse would most likely flare up to negative magnitudes and would easily be visible in the daytime if it popped off in the Spring or Fall. This time of year in June would be the worst, as Alpha Orionis only lies 15 degrees from the Sun!

Of course, this cosmic spectacle could kick off tomorrow… or thousands of years from now. Maybe, the light of Betelgeuse gone supernova is already on its way now, traversing the 650 light years of open space. Ironically, the last naked eye supernova in our galaxy – Kepler’s Star in the constellation Ophiuchus in 1604 – kicked off just before Galileo first turned his crude telescope towards the heavens in 1610.

You could say we’re due.