NASA’s Earth Observatory is a vital part of the space agency’s mission to advance our understanding of Earth, its climate, and the ways in which it is similar and different from the other Solar Planets. For decades, the EO has been monitoring Earth from space in order to map it’s surface, track it’s weather patterns, measure changes in our environment, and monitor major geological events.

For instance, Mount Sinabung – a stratovolcano located on the island of Sumatra in Indonesia – became sporadically active in 2010 after centuries of being dormant. But on February 19th, 2018, it erupted violently, spewing ash at least 5 to 7 kilometers (16,000 to 23,000 feet) into the air over Indonesia. Just a few hours later, Terra and other NASA Earth Observatory satellites captured the eruption from orbit.

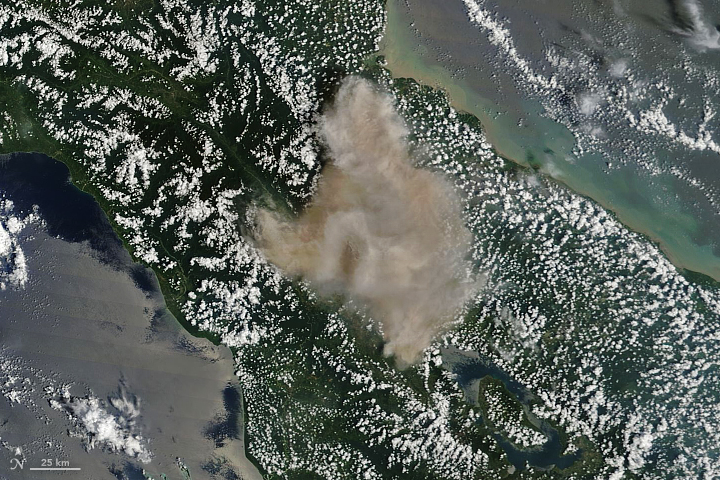

The images were taken with Terra’s Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS), which recorded a natural-color image of the eruption at 11:10 am local time (04:10 Universal Time). This was just hours after the eruption began and managed to illustrate what was being reported by sources on the ground. According to multiple reports from the Associated Press, the scene was one of carnage.

According to eye-witness accounts, the erupting lava dome obliterated a chunk of the peak as it erupted. This was followed by plumes of hot gas and ash riding down the volcano’s summit and spreading out in a 5-kilometer (3 mile) diameter. Ash falls were widespread, covering entire villages in the area and leading to airline pilots being issued the highest of alerts for the region.

In fact, ash falls were recorded as far as away as the town of Lhokseumawe – located some 260 km (160 mi) to the north. To address the threat to public health, the Indonesian government advised people to stay indoors due to poor air quality, and officials were dispatched to Sumatra to hand out face masks. Due to its composition and its particulate nature, volcanic ash is a severe health hazard.

On the one hand, it contains sulfur dioxide (SO²), which can irritate the human nose and throat when inhaled. The gas also reacts with water vapor in the atmosphere to produce acid rain, causing damage to vegetation and drinking water. It can also react with other gases in the atmosphere to form aerosol particles that can create thick hazes and even lead to global cooling.

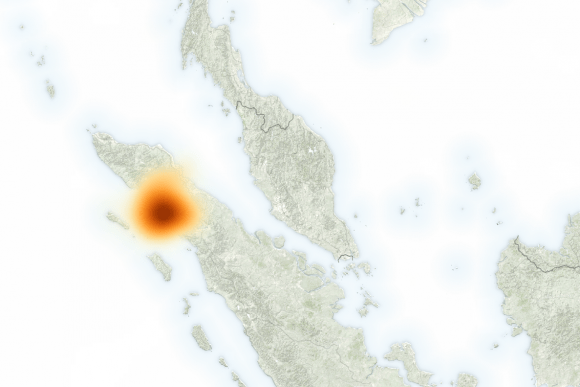

These levels were recorded by the Suomi-NPP satellite using its Ozone Mapper Profiler Suite (OMPS). The image below shows what SO² concentrations were like at 1:20 p.m. local time (06:20 Universal Time) on February 19th, several hours after the eruption. The maximum concentrations of SO² reached 140 Dobson Units in the immediate vicinity of the mountain.

Erik Klemetti, a volcanologist, was on hand to witness the event. As he explained in an article for Discovery Magazine:

“On February 19, 2018, the volcano decided to change its tune and unleashed a massive explosion that potentially reached at least 23,000 and possibly to up 55,000 feet (~16.5 kilometers), making it the largest eruption since the volcano became active again in 2013.”

Klemetti also cited a report that was recently filed by the Darwin Volcanic Ash Advisory Center – part of the Australian Government’s Bureau of Meteorology. According to this report, the ash will drift to the west and fall into the Indian Ocean, rather than continuing to rain down on Sumatra. Other sensors on NASA satellites have also been monitoring Mount Sinabung since its erupted.

This includes the Cloud-Aerosol Lidar and Infrared Pathfinder Satellite Observation (CALIPSO), an environmental satellite operated jointly by NASA and France’s Centre National d’Etudes Spatiales (CNES). Data from this satellite indicated that some debris and gas released by the eruption has risen as high as 15 to 18 km (mi) into the atmosphere.

In addition, data from the Aura satellite‘s Ozone Monitoring Instrument (OMI) recently indicated rising levels of SO² around Sinabung, which could mean that fresh magma is approaching the surface. As i concluded:

“This could just be a one-off blast from the volcano and it will return to its previous level of activity, but it is startling to say the least. Sinabung is still a massive humanitarian crisis, with tens of thousands of people unable to return to their homes for years. Some towns have even been rebuilt further from the volcano as it has shown no signs of ending this eruptive period.”

Be sure to check out this video of the eruption, courtesy of New Zealand Volcanologist Dr. Janine Krippner:

Further Reading: NASA Earth Observatory