One-one thou… That’s how long it takes for the International Space Station, traveling at over 17,000 mph (27,300 kph), to cross the face of the Full Moon. Only about a half second! To see it with your own eyes, you need to know exactly when and where to look. Full Moon is best, since it’s the biggest the moon can appear, but anything from a half-moon up and up will do.

The photo above was made by superimposing 13 separate images of the ISS passing in front of the Moon into one. Once the team knew when the pass would happen, they used a digital camera to fire a burst of exposures, capturing multiple moments of the silhouetted spacecraft.

The ISS transits the Full Moon in May 2016

The ISS is the largest structure in orbit, spanning the size of a football field, but at 250 miles (400 km) altitude, it only appears as big as a modest lunar crater. While taking a photo sequence demands careful planning, seeing a pass is bit easier. As you’d suspect, the chances of the space station lining up exactly with a small target like the Moon from any particular location is small. But the ISS Transit Finder makes the job simple.

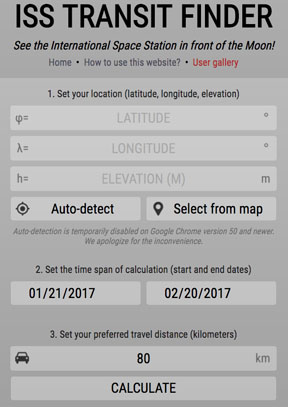

Click on the link and fill in your local latitude, longitude and altitude or select from the Google maps link shown. You can always find your precise latitude and longitude at NASA’s Latitude/Longitude Finder and altitude at Google Maps Find Altitude. Next, set the time span of your Moon transit search (up to one month from the current date) and then how far you’re willing to drive to see the ISS fly in front of the Moon.

When you click Calculate, you’ll get a list of events with little diagrams showing where the ISS will pass in relation to the Moon and sun (yes, the calculator also does solar disk crossings!) from your location. Notice that most of the passes will be near misses. However, if you click on the Show on Map link, you’ll get a ground track of exactly where you will need to travel to see it squarely cross Moon or Sun. Times shown are your local time, not Universal or UT.

The map also includes Recalculate for this location link. Clicking that will show you a sketch of the ISS’ predicted path across the Moon from the centerline location along with other details. I checked my city, and while there are no lunar transits for the next month, there’s a very nice solar one visible just a few miles from my home on Feb. 8. Remember to use a safe solar filter if you plan on viewing one of these!

While you might attempt to see a transit of the ISS in binoculars, your best bet is with a telescope. Nothing fancy required, just about any size will do so long as it magnifies at least 30x to 40x. Timing is crucial. Like an occultation, when the moon hides a background star in an instant, you want to be on time and 100% present.

Make sure you’re set up and focused on the moon or sun (with filter) at least 5 minutes beforehand. Keep your cellphone handy. I’ve found the time displayed at least on my phone to be accurate. One minute before the anticipated transit, glue your eye to the eyepiece, relax and wait for the flyby. Expect something like a bird in silhouette to make a swift dash across the moon’s face. The video above will help you anticipate what to expect.

Even if you never go to the trouble of identifying a “direct hit”, you can still use the transit finder to compile a list of cool lunar close approaches that would make for great photos with just a camera and tripod.

The Transit Finder isn’t the only way to predict ISS flybys. Some observers also use the excellent satellite site, CalSky. Once you tell it your location, select the Lunar/Solar Disk Crossings and Occultations link for lots of information including times, diagrams of crossings, ground tracks and more.

I use Stellarium (above) to make nifty simulated paths and show me where the Moon will be in the sky at the time of the transit. When you’ve downloaded the free program, get the latest satellite orbital elements this way:

* Move you cursor to the lower left of the window and select the Configuration box

* Click the Plugins tab and scroll down to Satellites and click Configure and then Update

* Hover the cursor at the bottom of the screen for a visual menu. Slide over to the satellite icon and click it once for Satellite hints. The ISS will now be active.

* Set the clock and location (lower left again) for the precise time and location, then do a search for the Moon, and you’ll see the ISS path.

There you have it — lots of options. Or you can simply use the Transit Finder and call it a day! I hope you’ll soon be in the right place at the right time to see the space station pass in front of the Moon. Checking my usual haunts, I see that the space station will be returning next weekend (Jan. 27) to begin an approximately 3-week run of easily viewable evening passes.