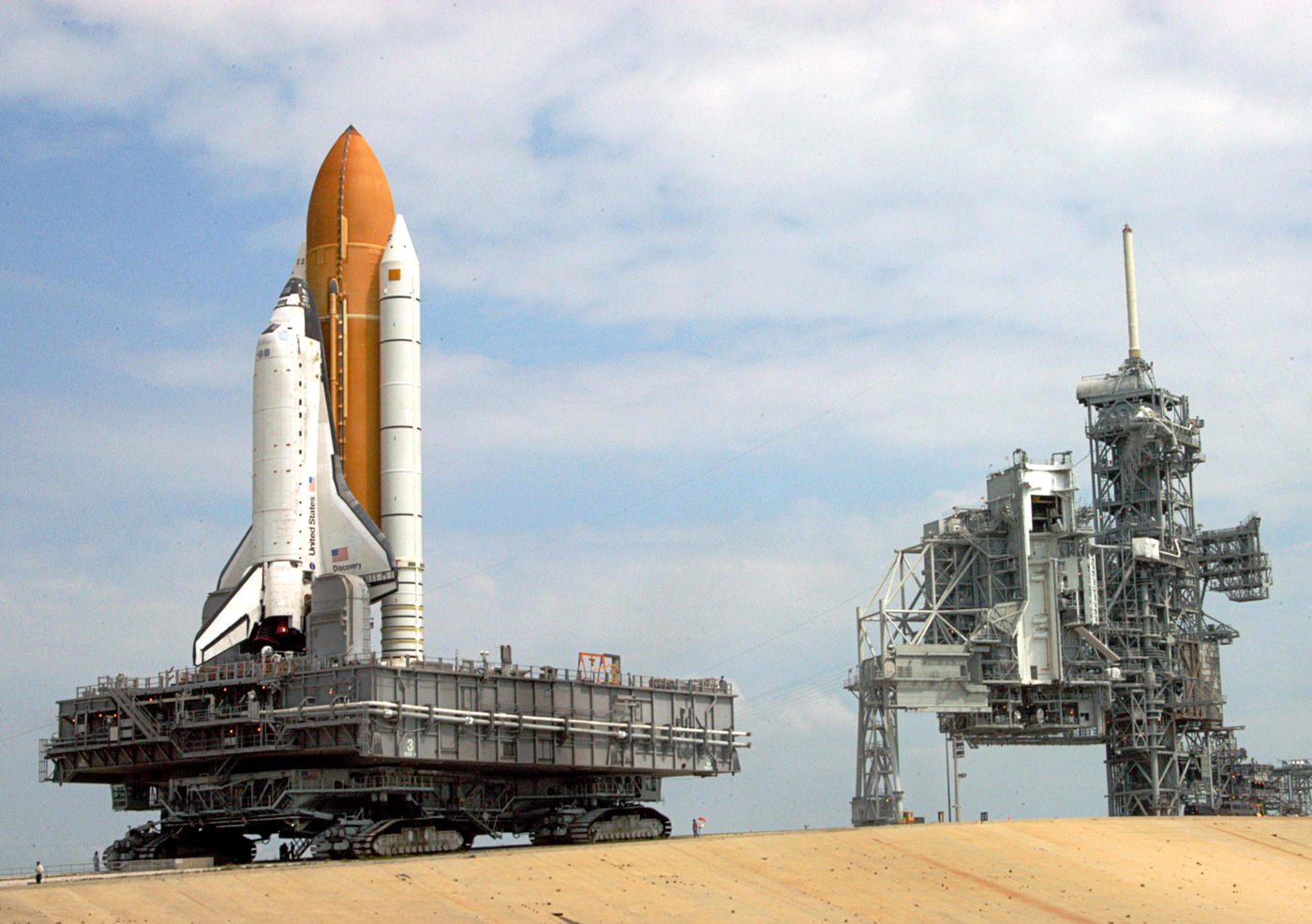

Shuttle Discovery riding one of KSC’s crawler-transporters to Launch Pad 39B in June 2005 (NASA)

One of NASA’s two iconic crawler-transporters — the 2,750-ton monster vehicles that have delivered rockets from Saturns to Shuttles to launch pads at Kennedy Space Center for nearly half a century — is getting an upgrade in preparation for NASA’s new future in space flight.

131 feet long, 113 feet wide and with a breakneck top speed of 2 mph (they’re strong, not fast!) NASA’s colossal crawler-transporters are the only machines capable of hauling fully-fueled rockets the size of office buildings safely between the Vehicle Assembly Building and the launch pads at Kennedy Space Center. Each 3.5-mile one-way trip takes around 6 hours.

131 feet long, 113 feet wide and with a breakneck top speed of 2 mph (they’re strong, not fast!) NASA’s colossal crawler-transporters are the only machines capable of hauling fully-fueled rockets the size of office buildings safely between the Vehicle Assembly Building and the launch pads at Kennedy Space Center. Each 3.5-mile one-way trip takes around 6 hours.

Now that the shuttles are retired and each in or destined for its permanent occupation as a relic of human spaceflight, the crawler-transporters have not been doing much crawling or transporting down the 130-foot-wide, Tennessee river-rock-coated lanes at KSC… but that’s soon to change.

According to an article posted Sept. 5 on TransportationNation.org, crawler 2 (CT-2) is getting a 6-million-pound upgrade, bringing its carrying capacity from 12 million pounds to 18 million. This will allow the vehicle to bear the weight of a new generation of heavy-lift rockets, including NASA’s Space Launch System (SLS).

Read: SLS: NASA’s Next Big Thing

In addition to carrying capacity CT-2 will also be getting new brakes, exhausts, hydraulics and computer systems.

Part of a $2 billion plan to upgrade Kennedy Space Center for a future with both NASA and commercial spaceflight partners, the crawler will have two of its onboard power engines replaced — but the original generators that power its eight enormous tread belts will remain, having been thoroughly inspected and deemed to be “in pristine condition” according to the article by Matthew Peddie.

When constructed in the early 1960s, the crawler-transporters were the largest tracked vehicles ever made and cost $14 million — that’s about $100 million today. But were they to be built from scratch now they’d likely cost even more, as the US “is no longer the industrial powerhouse it was in the 1960s.”

Still, it’s good to know that these hardworking behemoths will keep bringing rockets to the pad, even after the shuttles have been permanently parked.

“When they built the crawler, they overbuilt it, and that’s a great thing because it’s able to last all these years. I think it’s a great machine that could last another 50 years if it needed to,” said Bob Myers, systems engineer for the crawler.

You can see some really great full panoramas of the CT-2 at the NASATech website, where photographer John O’Connor took three different panoramic views while the transporter was inside the Vehicle Assembly Building at KSC in Highbay 1. There’s even a pan close-up of the giant cleats that move the transporter.

Read the full article on TransportationNation.org here, and find out more about the crawler-transporters here and here.

Since the Apollo years the transporters have traveled an accumulated 2,526 miles, about the same distance as a one-way highway trip from KSC to Los Angeles.

Inset image: the Apollo 11 Saturn V, tower and mobile launch platform atop the crawler-transporter during rollout on May 20, 1969. (NASA) Bottom image: NASA Administrator Charles Bolden on the site of the CT-2 upgrade in August 2012. Each of the crawler’s 456 tread shoes weighs about one ton. (NASA)