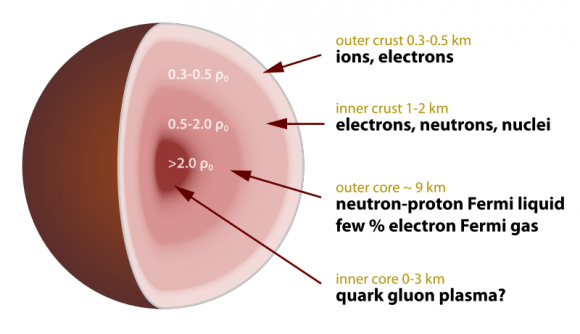

Neutron stars are famous for combining a very high-density with a very small radius. As the remnants of massive stars that have undergone gravitational collapse, the interior of a neutron star is compressed to the point where they have similar pressure conditions to atomic nuclei. Basically, they become so dense that they experience the same amount of internal pressure as the equivalent of 2.6 to 4.1 quadrillion Suns!

In spite of that, neutron stars have nothing on protons, according to a recent study by scientists at the Department of Energy’s Thomas Jefferson National Accelerator Facility. After conducting the first measurement of the mechanical properties of subatomic particles, the scientific team determined that near the center of a proton, the pressure is about 10 times greater than the pressure in the heart of a neutron star.

The study which describes the team’s findings, titled “The pressure distribution inside the proton“, recently appeared in the scientific journal Nature. The study was led by Volker Burkert, a nuclear physicist at the Thomas Jefferson National Accelerator Facility (TJNAF), and co-authored by

Basically , they found that the pressure conditions at the center of a proton were 100 decillion pascals – about 10 times the pressure at the heart of a neutron star. However, they also found that pressure inside the particle is not uniform, and drops off as the distance from the center increases. As Volker Burkert, the Jefferson Lab Hall B Leader, explained:

“We found an extremely high outward-directed pressure from the center of the proton, and a much lower and more extended inward-directed pressure near the proton’s periphery… Our results also shed light on the distribution of the strong force inside the proton. We are providing a way of visualizing the magnitude and distribution of the strong force inside the proton. This opens up an entirely new direction in nuclear and particle physics that can be explored in the future.”

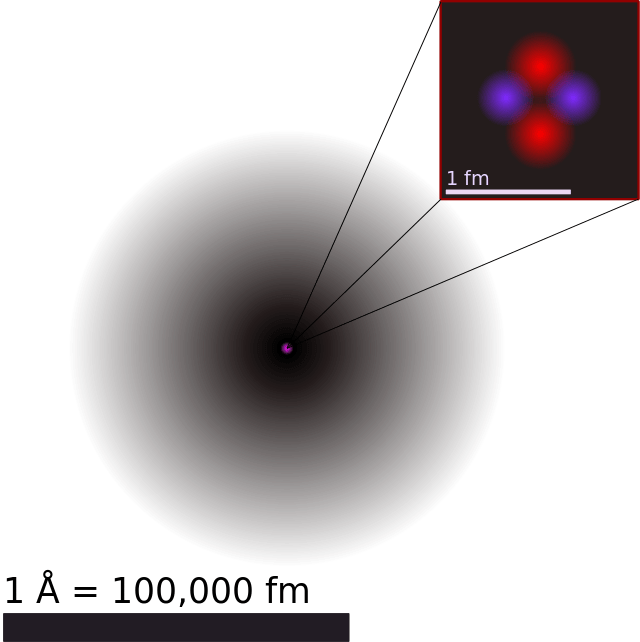

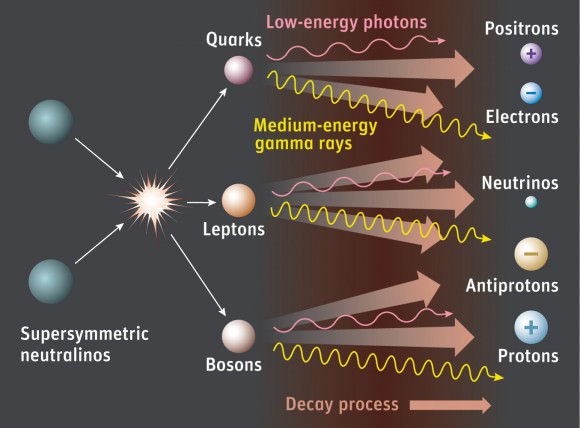

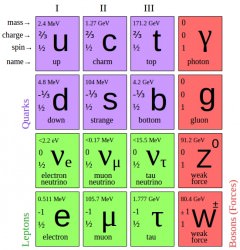

Protons are composed of three quarks that are bound together by the strong nuclear force, one of the four fundamental forces that government the Universe – the other being electromagnetism, gravity and weak nuclear forces. Whereas electromagnetism and gravity produce the effects that govern matter on the larger scales, weak and strong nuclear forces govern matter at the subatomic level.

Previously, scientists thought that it was impossible to obtain detailed information about subatomic particles. However, the researchers were able to obtain results by pairing two theoretical frameworks with existing data, which consisted of modelling systems that rely on electromagnetism and gravity. The first model concerns generalized parton distributions (GDP) while the second involve gravitational form factors.

Patron modelling refers to modeling subatomic entities (like quarks) inside protons and neutrons, which allows scientist to create 3D images of a proton’s or neutron’s structure (as probed by the electromagnetic force). The second model describes the scattering of subatomic particles by classical gravitational fields, which describes the mechanical structure of protons when probed via the gravitational force.

As noted, scientists previously thought that this was impossible due to the extreme weakness of the gravitational interaction. However, recent theoretical work has indicated that it could be possible to determine the mechanical structure of a proton using electromagnetic probes as a substitute for gravitational probes. According to Latifa Elouadrhiri – a Jefferson Lab staff scientist and co-author on the paper – that is what their team set out to prove.

“This is the beauty of it. You have this map that you think you will never get,” she said. “But here we are, filling it in with this electromagnetic probe.”

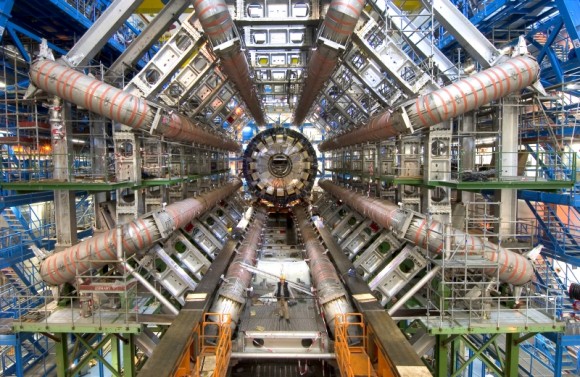

For the sake of their study, the team used the DOE’s Continuous Electron Beam Accelerator Facility at the TJNAF to create a beam of electrons. These were then directed into the nuclei of atoms where they interacted electromagnetically with the quarks inside protons via a process called deeply virtual Compton scattering (DVCS). In this process, an electron exchanges a virtual photon with a quark, transferring energy to the quark and proton.

Shortly thereafter, the proton releases this energy by emitting another photon while remaining intact. Through this process, the team was able to produced detailed information of the mechanics going on in inside the protons they probed. As Francois-Xavier Girod, a Jefferson Lab staff scientist and co-author on the paper, explained the process:

“There’s a photon coming in and a photon coming out. And the pair of photons both are spin-1. That gives us the same information as exchanging one graviton particle with spin-2. So now, one can basically do the same thing that we have done in electromagnetic processes — but relative to the gravitational form factors, which represent the mechanical structure of the proton.”

The next step, according to the research team, will be to apply the technique to even more precise data that will soon be released. This will reduce uncertainties in the current analysis and allow the team to reveal other mechanical properties inside protons – like the internal shear forces and the proton’s mechanical radius. These results, and those the team hope to reveal in the future, are sure to be of interest to other physicists.

“We are providing a way of visualizing the magnitude and distribution of the strong force inside the proton,” said Burkert. “This opens up an entirely new direction in nuclear and particle physics that can be explored in the future.”

Perhaps, just perhaps, it will bring us closer to understanding how the four fundamental forces of the Universe interact. While scientists understand how electromagnetism and weak and strong nuclear forces interact with each other (as described by Quantum Mechanics), they are still unsure how these interact with gravity (as described by General Relativity).

If and when the four forces can be unified in a Theory of Everything (ToE), one of the last and greatest hurdles to a complete understanding of the Universe will finally be removed.

Further Reading: Jefferson Lab, Cosmos Magazine, Nature