[/caption]

It seems oddly appropriate to be writing about astrophysical jets on Thanksgiving Day, when the New York football Jets will be featured on television. In the most recent issue of Science, Carlos Carrasco-Gonzalez and collaborators write about how their observations of radio emissions from young stellar objects (YSOs) shed light one of the unsolved problems in astrophysics; what are the mechanisms that form the streams of plasma known as polar jets? Although we are still early in the game, Carrasco-Gonzalez et al have moved us closer to the goal line with their discovery.

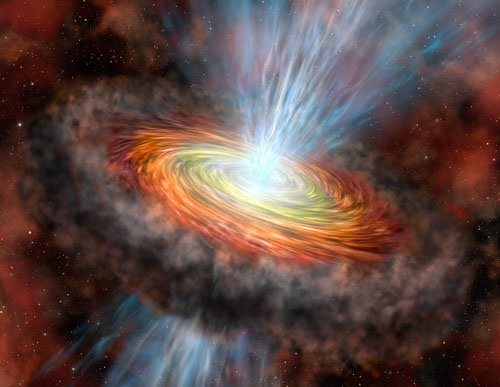

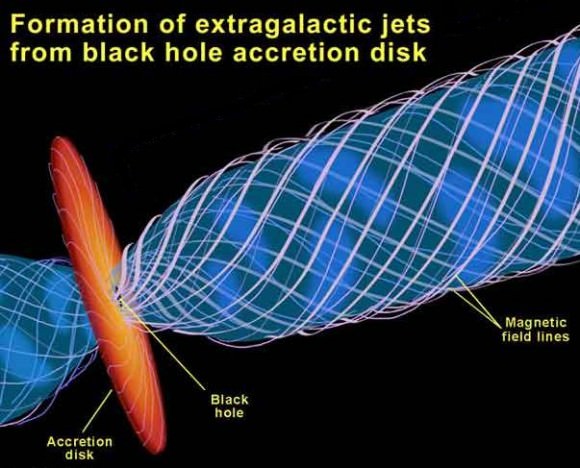

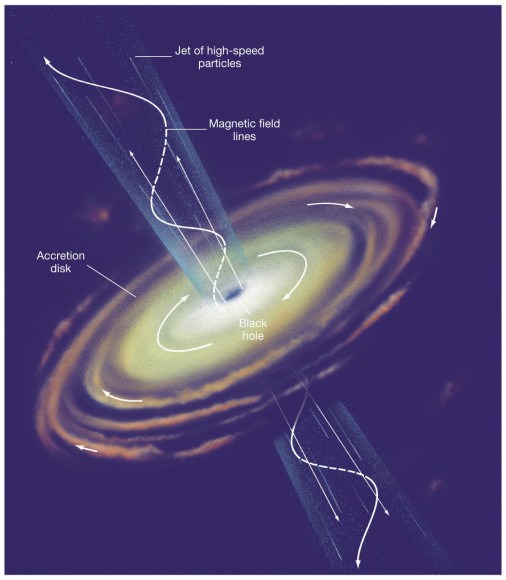

Astronomers see polar jets in many places in the Universe. The largest polar jets are those seen in active galaxies such as quasars. They are also found in gamma-ray bursters, cataclysmic variable stars, X-ray binaries and protostars in the process of becoming main sequence stars. All these objects have several features in common: a central gravitational source, such as a black hole or white dwarf, an accretion disk, diffuse matter orbiting around the central mass, and a strong magnetic field.

When matter is emitted at speeds approaching the speed of light, these jets are called relativistic jets. These are normally the jets produced by supermassive black holes in active galaxies. These jets emit energy in the form of radio waves produced by electrons as they spiral around magnetic fields, a process called synchrotron emission. Extremely distant active galactic nuclei (AGN) have been mapped out in great detail using radio interferometers like the Very Large Array in New Mexico. These emissions can be used to estimate the direction and intensity of AGNs magnetic fields, but other basic information, such as the velocity and amount of mass loss, are not well known.

On the other hand, astronomers know a great deal about the polar jets emitted by young stars through the emission lines in their spectra. The density, temperature and radial velocity of nearby stellar jets can be measured very well. The only thing missing from the recipe is the strength of the magnetic field. Ironically, this is the one thing that we can measure well in distant AGN. It seemed unlikely that stellar jets would produce synchrotron emissions since the temperatures in these jets are usually only a few thousand degrees. The exciting news from Carrasco-Gonzalez et al is that jets from young stars do emit synchrotron radiation, which allowed them to measure the strength and direction of the magnetic field in the massive Herbig-Haro object, HH 80-81, a protostar 10 times as massive and 17,000 times more luminous than our Sun.

Finally obtaining data related to the intensity and orientation of the magnetic field lines in YSO’s and their similarity to the characteristics of AGN suggests we may be that much closer to understanding the common origin of all astrophysical jets. Yet another thing to be thankful for on this day.