[/caption]

Last week, scientists announced findings based on data from the SPICAM spectrometer onboard ESA’s Mars Express spacecraft. The findings reported in Science by Maltagliati et al (2011), reveal that the Martian atmosphere is supersaturated with water vapor. According to the research team, the discovery provides new information which will help scientists better understand the water cycle and atmospheric history of Mars.

What processes are at work to allow large amounts of water vapor in the Martian atmosphere?

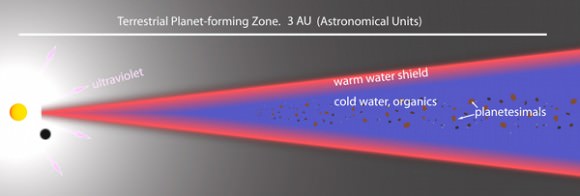

The animated sequence to the left shows the water cycle of the Martian atmosphere in action:

The animated sequence to the left shows the water cycle of the Martian atmosphere in action:

When the polar caps of Mars (which contain frozen Water and CO2) are warmed by the Sun during spring and summer, the water sublimates and is released into the atmosphere.

Atmospheric winds transport the water vapor molecules to higher altitudes. When the water molecules combine with dust molecules, clouds are formed. If there isn’t much dust in the atmosphere, the rate of condensation is reduced, which leaves water vapor in the atmosphere, creating a supersaturated state.

Water vapor may also be transported by wind to the southern hemisphere or may be carried high in the atmosphere.In the upper atmosphere the water vapor can be affected by photodissociation in which solar radiation (white arrows) splits the water molecules into hydrogen and oxygen atoms, which then escape into space.

Scientists had generally assumed that supersaturation cannot exist in the cold Martian atmosphere, believing that any water vapor in excess of saturation instantly froze. Data from SPICAM revealed that supersaturation takes place at altitudes of up to 50 km above the surface when Mars is at its farthest point from the Sun.

Based on the SPICAM data, scientists have learned that there is more water vapor in the Martian atmosphere than previously believed. While the amount of water in Mars’ atmosphere is about 10,000 times less water vapor than that of Earth, previous models have underestimated the amount of water in the Martian atmosphere at altitudes of 20-50km, as the data suggests 10 to 100 times more water than expected at said altitudes.

“The vertical distribution of water vapour is a key factor in the study of Mars’ hydrological cycle, and the old paradigm that it is mainly controlled by saturation physics now needs to be revised,” said Luca Maltagliati, one of the authors of the paper. “Our finding has major implications for understanding the planet’s global climate and the transport of water from one hemisphere to the other.”

“The data suggest that much more water vapour is being carried high enough in the atmosphere to be affected by photodissociation,” added Franck Montmessin, Principal Investigator for SPICAM and co-author of the paper.

“Solar radiation can split the water molecules into oxygen and hydrogen atoms, which can then escape into space. This has implications for the rate at which water has been lost from the planet and for the long-term evolution of the Martian surface and atmosphere.”

However, water vapour is a very dynamic trace gas, and one of the most seasonally variable atmospheric constituents on Mars.

Source: ESA/Mars Express Mission Updates