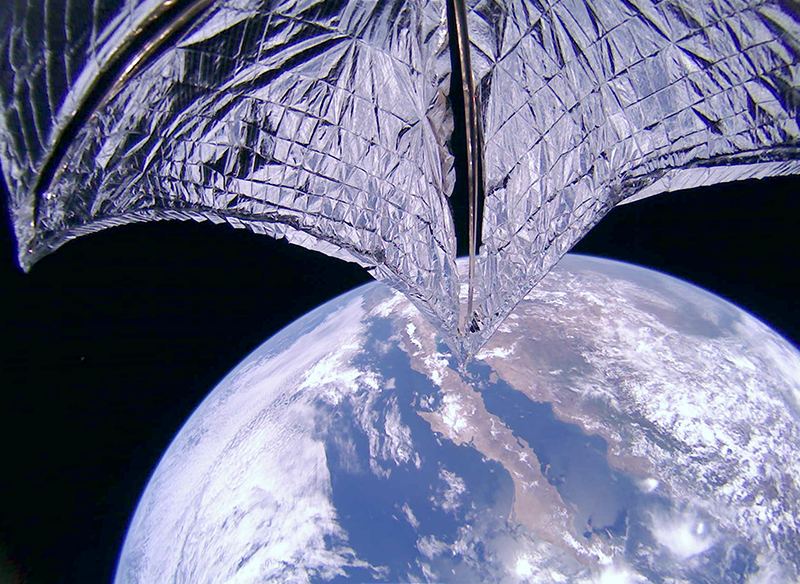

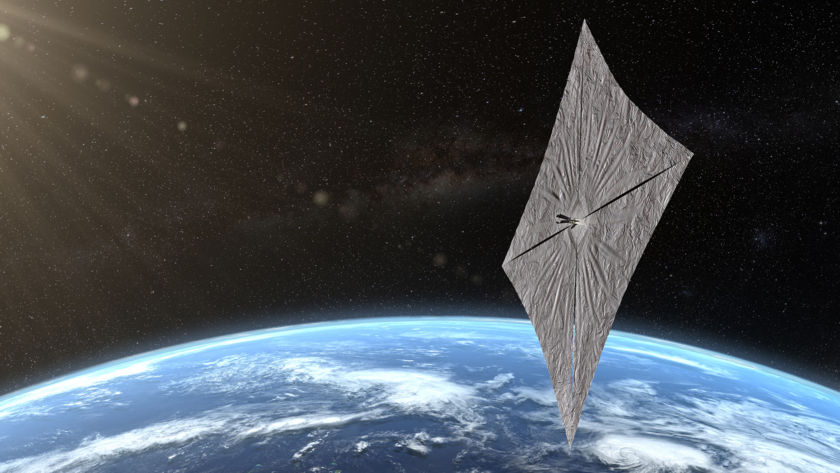

The Planetary Society’s crowdfunded solar-sailing CubeSat, LightSail 2, launched on June 25th 2019, and two years later the mission is still going strong. A pioneering technology demonstration of solar sail capability, LightSail 2 uses the gentle push of photons from the Sun to maneuver and adjust its orbital trajectory. Within months of its launch, LightSail 2 had already been declared a success, breaking new ground and expanding the possibilities for future spacecraft propulsion systems. Since then, it’s gone on to test the limits of solar sailing in an ongoing extended mission.

Continue reading “LightSail 2 Has Now Been in Space for 2 Years, and Should Last Even Longer Before Re-Entering the Atmosphere”Planetary Society Deploys LightSail 2’s Solar Sail. What Does The Future Hold For Solar Sails?

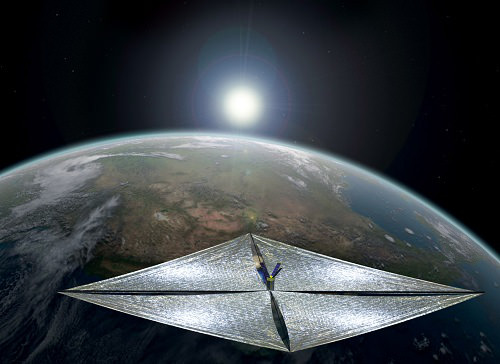

Where you can travel in space depends on how much propellant you’ve got on board your rocket and how efficiently you can use it. But there’s a source of free propellant right here in the Solar System – the Sun – which is streaming out photons in all directions. You just need to catch them.

And right now, the Planetary Society’s new LightSail 2 spacecraft is testing out just how well it’ll work.

Continue reading “Planetary Society Deploys LightSail 2’s Solar Sail. What Does The Future Hold For Solar Sails?”Planetary Society’s Light Sail 2 is Set to Launch on a Falcon Heavy Rocket Next Month

The Planetary Society is going to launch their LightSail 2 CubeSat next month. LightSail 2 is a test mission designed to study the feasibility of using sunlight for propulsion. The small satellite will use the pressure of sunlight on its solar sails to propel its way to a higher orbit.

Continue reading “Planetary Society’s Light Sail 2 is Set to Launch on a Falcon Heavy Rocket Next Month”Weekly Space Hangout: Nov 21, 2018: Bruce Betts’ “Astronomy for Kids”

Hosts:

Fraser Cain (universetoday.com / @fcain)

Dr. Paul M. Sutter (pmsutter.com / @PaulMattSutter)

Dr. Kimberly Cartier (KimberlyCartier.org / @AstroKimCartier )

Dr. Morgan Rehnberg (MorganRehnberg.com / @MorganRehnberg & ChartYourWorld.org)

This week, we are joined by Dr. Bruce Betts, Chief Scientist and LightSail Program Manager for The Planetary Society. Prior to working on the LightSail program, Dr. Betts managed a number of flight instrument projects at the Planetary Society, including silica glass DVDs on the Mars Exploration Rovers and Phoenix lander, the LIFE biology experiment that flew on the Russian Phobos sample return mission, and he led a NASA grant studying microrovers assisting human exploration. Dr. Betts new children’s book, “”Astronomy for Kids: How to Observe Outer Space with a Telescope, Binoculars, or Just Your Eyes!”” is now available in time for holiday gift giving.

Prior to joining the Planetary Society, Dr. Betts, a planetary scientist, studied planetary surfaces, including Mars, the Moon, and Jupiter’s moons, using infrared and other data, during his time at San Juan Institute/Planetary Science Institute. Additionally, Dr. Betts spent three years at NASA headquarters managing planetary instrument development programs to design spacecraft science instruments.

You can learn more about Dr. Betts by visiting http://www.planetary.org/about/staff/bruce-betts.html.

If you want to learn about his new book and how to order it, visit http://www.planetary.org/blogs/bruce-betts/astronomy-for-kids.html

Announcements:

Want to support CosmoQuest? Here are specific ways you can help:

* Donate! (Streamlabs link) https://streamlabs.com/cosmoquestx

* Buy stuff from our Redbubble https://www.redbubble.com/people/cosmoquestx

* Volunteer for our Hangout-a-thon either to promote, provide a giveaway, or to come on as a guest https://goo.gl/forms/XSm1yi0PKOM166m12

* Help us find sponsors by sharing our program and fundraising efforts through your networks

* Become a Patreon of Astronomy Cast https://www.patreon.com/astronomycast

* Sponsor 365 Days of Astronomy http://bit.ly/sponsor365DoA

* A combination of the above!

If you would like to join the Weekly Space Hangout Crew, visit their site here and sign up. They’re a great team who can help you join our online discussions!

If you’d like to join Dr. Paul Sutter and Dr. Pamela Gay on their Cosmic Stories in the SouthWest Tour in August 2019, you can find the information at astrotours.co/southwest.

We record the Weekly Space Hangout every Wednesday at 5:00 pm Pacific / 8:00 pm Eastern. You can watch us live on Universe Today, or the Weekly Space Hangout YouTube page – Please subscribe!

The Weekly Space Hangout is a production of CosmoQuest.

Weekly Space Hangout: Oct 3, 2018 – Dr. David Warmflash

Hosts:

Fraser Cain (universetoday.com / @fcain)

Dr. Paul M. Sutter (pmsutter.com / @PaulMattSutter)

Dr. Kimberly Cartier (KimberlyCartier.org / @AstroKimCartier )

Dr. Morgan Rehnberg (MorganRehnberg.com / @MorganRehnberg & ChartYourWorld.org)

This week’s special guest is Dr. David Warmflash. Dr. Warmflash is an astrobiologist and science writer. He received his M.D. from Tel Aviv University Sackler School of Medicine, and has done post doctoral work at Brandeis University, the University of Pennsylvania, and the Johnson Space Center, where he was a NASA astrobiology training fellow. He has been involved in science outreach for more than a decade, including having collaborated with The Planetary Society on studying the effects of the space environment on small organisms.

As a prolific freelance science communicator, David has had numerous articles published, his most recent being “”Should the Moon be Quarantined?”” which appears in the current issue of Scientific American (https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/should-the-moon-be-quarantined/).

You can find David on Twitter (@CosmicEvolution)

Announcements:

If you would like to join the Weekly Space Hangout Crew, visit their site here and sign up. They’re a great team who can help you join our online discussions!

If you’d like to join Dr. Paul Sutter and Dr. Pamela Gay on their Cosmic Stories in the SouthWest Tour in August 2019, you can find the information at astrotours.co/southwest.

We record the Weekly Space Hangout every Wednesday at 5:00 pm Pacific / 8:00 pm Eastern. You can watch us live on Universe Today, or the Weekly Space Hangout YouTube page – Please subscribe!

We’re Finally Sending Ears to Mars

We all love that feeling of “being there” when it comes to missions to other planets. Juno’s arrival at Jupiter, New Horizons’ flyby of Pluto and the daily upload of raw images from the Mars Curiosity rover makes each of us an armchair explorer of alien landscapes. But there’s always been something missing. Something essential in shaping our environment — sound.

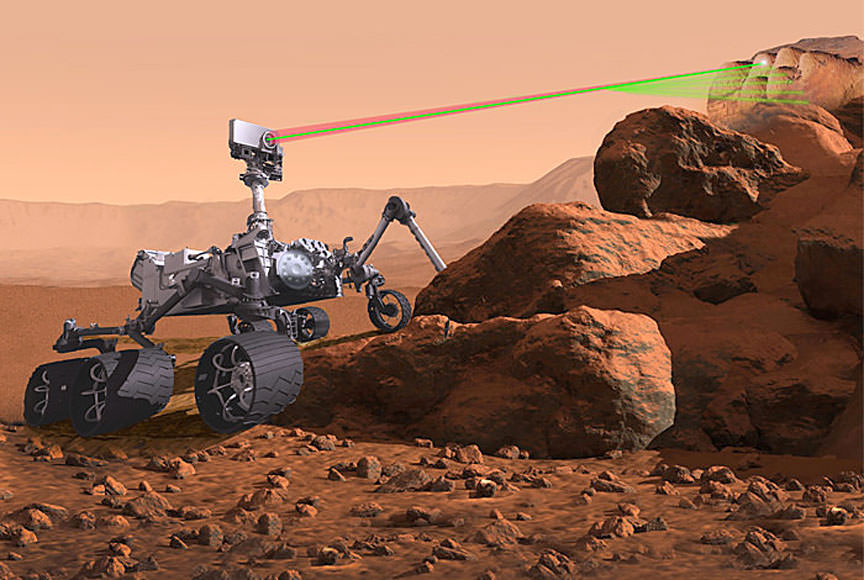

NASA recently gave the go-ahead for the Mars 2020 rover that will bristle with a new suite of science instruments including a microphone. Hallelujah! Finally, we’ll get to listen to the sound of the Martian wind, the occasional whirl of dust devils, the crunch of rocks beneath the rover’s wheels and even sharp pops from laser-zapped rocks!

The staff and membership of The Planetary Society have been trying for 20 years to get a working microphone to the Red Planet. One flew aboard NASA’s Mars Polar Lander mission in 1998 but that probe crashed landed when its engine shut down prematurely during the descent phase. In 2008 the Society partnered with Malin Space Science Systems to include its next microphone in the descent imager package on the Mars Phoenix lander in 2008. While that mission was successful, the imager (along with its microphone) was turned off for fear it might cause an electrical problem with a critical landing system. Mission planners hoped it might be turned on later but whether it was a money issue or fear of shorting out other critical lander instruments, it never happened. Heartbreaking.

One sound souvenir we did get from Phoenix comes to us from the European Space Agency’s Mars which recorded the radio transmissions from the lander as it descended. The signals were then processed into audio within the range of human hearing. Give a listen, there’s a music to it.

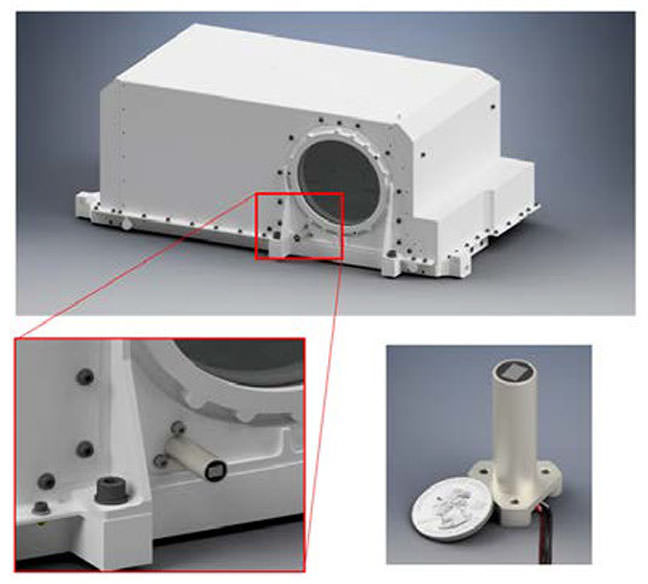

The Mars 2020 mission, which is expected to launch in the summer of 2020 and land the following February, will search directly for signs of ancient Martian life as well as identify and cache samples and specimens at several locations on the surface for pick-up by later missions. The microphone would be housed with the rover’s SuperCam, a souped-up version of Curiosity’s ChemCam, which fires a laser at rocks and soils from a distance to analyze the resulting vapors for their elemental composition.

SuperCam will also shoot a laser to vaporize rocks and spectroscopy to tease out their molecular and mineral composition. The microphone would be mounted on a tube sticking out of the electronics box housing SuperCam and used for scientific purposes but I suspect for public outreach as well. One of its more intriguing uses will be to record the ‘snap’ or ‘pop’ when a rock is struck with the laser. Based on the volume of the sound, scientists can estimate the specimen’s mass.

NASA plans to land the 1-ton rover using the same sky crane method that settled Curiosity to the surface in dramatic fashion. While the rover will be busy photographing the entry, descent and landing sequence, the microphone will record the ambient sound. Synched together, this should make for one of the most compelling videos ever!

The microphone will also be used to augment studies of Martian weather (the aforementioned winds and dust devils) and listen to the rover’s creaks, groans and whir of its motors as the car-sized machine rolls across the alternately sandy and rocky surface of Mars. The Planetary Society is collaborating with the SuperCam team to make the most of the microphone. Who knows what else we might hear? Exploding fireball overhead? Static electricity? Rhythmic winds? Blowing sand? Slime-slap of alien pseudopods? OK, probably not the last one, but new instruments often reveal completely unexpected phenomena.

It’s been hard as hell getting a microphone on a space mission. They’ve had to compete with other instruments considered more essential not to mention the precious space the device would take up and the burden of additional mass. Mission planners consider every fraction of a gram when building a space probe because getting it into Earth orbit and blasting it to a planet takes energy. Rockets only hold so much fuel!

Your Voice on Mars

You might wonder if Mars’ atmosphere is thick enough to carry sound. The good news is that it is, but unlike Earth’s much denser nitrogen-oxygen mix, Martian air is 100 times thinner and composed of 95% carbon dioxide. If you could snap off your helmet and talk out loud on the Red Planet, your voice would sound deeper and not travel as far. Scientists liken it to having a conversation at 100,000 feet (30,500 meters) above Earth’s surface. Check out the crazy video for a simulation.

Now that you’ve made it to the end of this story, sit back and pump up the volume. We’ll have ears on Mars soon!

Pump Up the Volume by M|A|R|R|S

Will We Ever Reach Another Star?

We hear about discoveries of exoplanets every day. So how long will it take us to find another planet like Earth?

There are two separate parts of your brain I would like to speak with today. First, I want to talk to the part that makes decisions on who to vote for, how much insurance you should put on your car and deals with how not paying taxes sends you to jail. We’ll call this part of your brain “Kevin”.

The rest of your brain can kick back, especially the parts that knows what kind of gas station you prefer, whether Lena Dunham is awesome or “the most awesome”, whether a certain sports team is the winningest, or believes that you can leave a casino with more money than you went in with. We will call this part “Other Kevin”, in honor of Dave Willis.

Okay Kevin, you’re up. I’m going to cut to the gut punch, Kevin. Between you and me, it is my displeasure to inform you that science fiction has ruined “Other Kevin”. Just like comic books have compromised their ability to judge the likelihood of someone acquiring heat vision, science fiction has messed up their sense of scale about interstellar travel.

But you already knew that. Not like “Other Kevin”, you’re the smart one. In the immortal words of Douglas Adams, “space is big”. But when he said that, Douglas was really understating how mind-bogglingly big space really is.

The nearest star is 4 light years away. That means that light, traveling at 300,000 kilometers per second would still need 4 YEARS to reach the nearest star. The fastest spacecraft ever launched by humans would need tens of thousands of years to make that trip.

But science fiction encourages us to think it’s possible. Kirk and Spock zip from world to world with a warp drive violating the Prime Directive right in it’s smug little Roddenberrian face. Han and Chewy can make the Kessel run in only 12 parsecs, which is confusing and requires fan theories to resolve the cognitive space-distance dissonance, and Galactica, The SDF 3, and Guild Navigators all participate in the folding of space.

And science fiction knows everything that’s about to happen, right? Like cellphones. Additionally Kevin, I know what you’re thinking and I’m not going to tear into Lucas on this. It’s too easy, and my ilk do it a little too often. Plus, I’m saving it up for Abrams. Sorry Kevin. Got a little distracted there.

The point is, science fiction is doing colossal hand waving. They’re glossing over key obstacles, like the laws of physics.

Stay with me here.This isn’t like jaywalking bylaws that “probably don’t apply to you at that very moment”, these are the physical laws of the universe that will deliver a complete junk-kicking if you try and pretend they’re not interested in crushing your little atmosphere requiring, century lifespan, conventional propulsion drive dreams.

So let’s say that we wanted to actually send a spacecraft to another star, whilst obeying the laws of physics. We’ll set the bar super low. We’re not talking about massive cruise ships filled with tourists seeking the delights of the super funzone planetoid, Itchy and Scrachylandia Prime.

I’m not talking about sending a crack team of power armored space marines to defend colonists from xenomorphs, or perhaps take other more thorough measures.

No, I’m talking about getting an operational teeny robotic spacecraft from Earth to Alpha Centauri. The fastest spacecraft we’ve ever launched is New Horizons. It’s currently traveling at 14 kilometres per second. It would take this peppy little probevette 100,000 years to get to the nearest star.

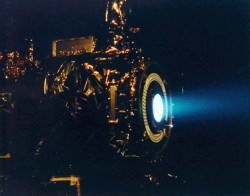

This is mostly due to our lack of reality shattering propulsion. Our best propellant option is an ion engine, used by NASA’s Dawn spacecraft. According to much adored Ian “Handsome” O’Neill from Discovery Space, we’d be looking at 19,000 years to get to Alpha Centauri if we used an ion engine and added a gravitational assist from the Sun.

Just think of what we could do with those 81,000 years we’d be saving! I’m going to learn the dulcimer!

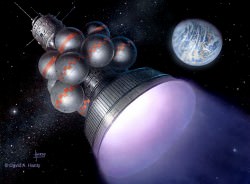

We can start shearing back the reality curtain and throw money and resources to chase nearby speculative propulsion tech. Things like antimatter engines, or even dropping nuclear bombs out the back of a spacecraft

The best idea in the hopper is to use solar sails, like the Planetary Society’s Lightsail.

Use the light from the Sun as well as powerful lasers to accelerate the craft.

But if we’re going to start down that road, we could also send microscopic lightsail spacecraft which are much easier to accelerate. Once these miniprobes reached their target, they could link up and form a communications relay, or even robotic factories.

Sorry, I think that was my “Other Kevin” talking. So where are we at, fo’ reals?

Harold “Sonny” White, a researcher with NASA announced that they’ve been testing out a futuristic technology called an EM drive. They detected a very slight “thrust” in their equipment that might mean it could be possible to maybe push a spacecraft in space without having to expel propellent like a chemical rocket or an ion drive.

What’s that, Kevin? Yes, you should totally be skeptical. You’re right, that last bit was a salad of weasel words.

Even if this crazy drive actually works, it still needs to obey the laws of physics. You couldn’t go faster than the speed of light and you would need a remarkable source of energy to power the reactor. Also, yes, Kevin, you’re right NASA is working on a warp drive. There’s no need to yell.

NASA is also working on an actual warp drive concept known as an alcubierre drive. It would actually do what science fiction has claimed: to warp space to allow faster than light travel. But by working on it, I mean, they’ve done a lot of fancy math.

But once they get all the math done, they can just go build it right? This concept is so theoretical that physicists are still arguing whether powering an alcubierre drive would take more energy than contained within the entire Universe. Which, I think we can call an obstacle.

Oh, one more thing. “Other Kevin”, thanks for being so patient. Here’s your reward. Unicorns are real, and Kevin has been lying to you this whole time. Go get ‘em tiger. Place your bets. When do you think we’ll send our first probe towards another star? Predict the departure date in the comments below.

Weekly Space Hangout – May 23, 2015: Dr. Rhys Taylor

Host: Fraser Cain (@fcain)

Special Guest:Dr. Rhys Taylor, Former Arecibo Post Doc; Current research involves looking for galaxies in the 21cm waveband.

Guests:

Morgan Rehnberg (cosmicchatter.org / @MorganRehnberg )

Alessondra Springmann (@sondy)

Continue reading “Weekly Space Hangout – May 23, 2015: Dr. Rhys Taylor”

Hunting LightSail in Orbit

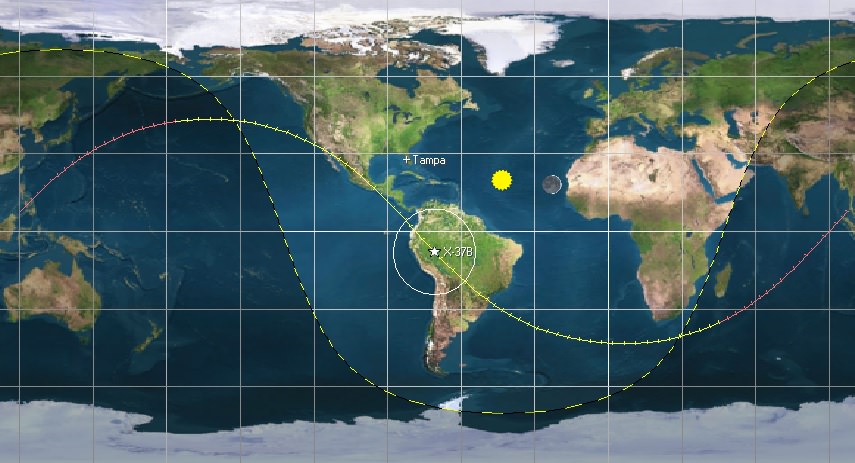

The hunt is on in the satellite tracking community, as the U.S. Air Force’s super-secret X-37B space plane rocketed into orbit today atop an Atlas V rocket out of Cape Canaveral. This marks the start of OTV-4, the X-37B’s fourth trip into low Earth orbit. And though NORAD won’t be publishing the orbital elements for the mission, it is sure to provide an interesting hunt for backyard satellite sleuths on the ground.

Previous OTV missions were placed in a 40 to 43.5 degree inclination orbit, and the current NOTAMs cite a 61 degree azimuth angle for today’s launch out of the Cape which suggests a slightly shallower 39 degree orbit. Such variability speaks to the versatile nature of the second stage Centaur motor.

There’s also been word afoot that future X-37B missions may return to Earth at the Kennedy Space Center, just like the Space Shuttle. To date, the X-37B has only landed at Vandenberg Air Force Base in California.

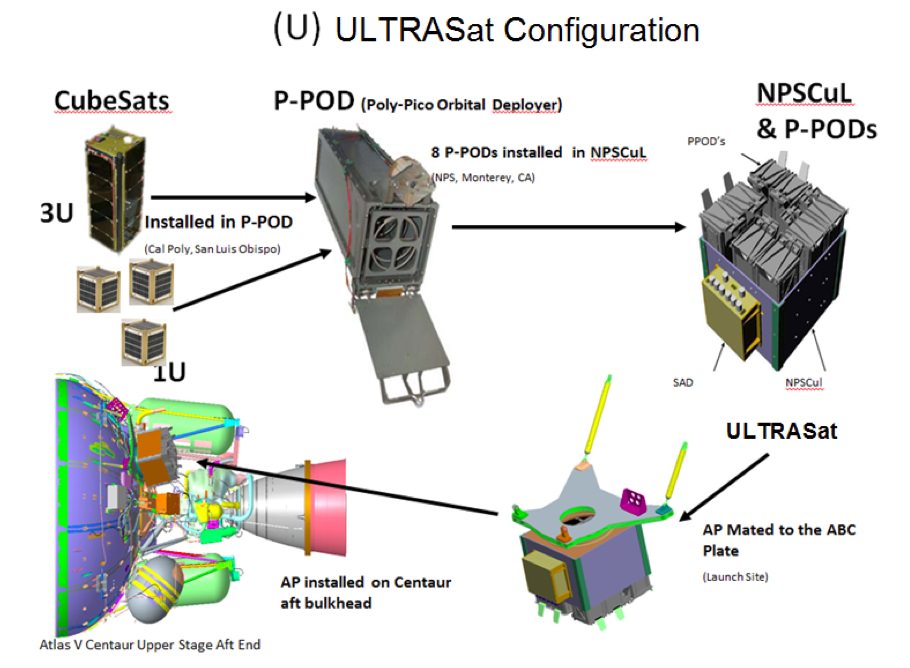

But there’s also another high interest payload being released along with a flock of CubeSats aboard AFPSC-5: The Planetary Society’s Lightsail-1.

About the size of a loaf of bread and the result of a successful Kickstarter campaign, LightSail is set to demonstrate key technologies in low Earth orbit before the Planetary Society’s main solar sail demonstrator takes to space in 2016.

The idea of using solar wind pressure for space travel is an enticing one. A big plus is the fact that unlike chemical propulsion, a solar sail does not need to contend with hauling the mass of its own fuel. The idea of using a solar sail plus a focused laser to propel an interstellar spacecraft has long been a staple of science fiction. But light-sailing technology has had a troubled history—the Planetary Society lost its Cosmos-1 mission launched from a Russian submarine in 2001. JAXA has fared better with its Venus-bound IKAROS, also equipped with a solar sail. To date, the IKAROS solar sail is the largest that has been deployed, at 20-metres on the diagonal.

Another use for space sail technology is the commanded reentry of spacecraft at the end of their mission life, as demonstrated by NanoSail-D2 in 2011.

Prospects of seeing LightSail may well be similar to what we had hunting for NanoSail-D2. Unfolded, LightSail will be 32 square meters in size, or about 5.6 meters on a side. NanoSail-D2 measured 3.1 meters on a side, and the reflective panels on the Iridium satellites which produce brilliant Iridium flares exceeding Venus in brightness measure about the size of a large rectangular door at 1 x 3 meters. Even the Hubble Space Telescope can flare on occasion as seen from the ground if one of its massive solar arrays catches the Sun just right.

The 39 degree orbital inclination angle will also limit visible passes to from about 45 degrees north to 45 degrees south latitude.

Hunting down X-37B and LightSail will push ground observing skills to the max. Like NanoSail-D2, LightSail probably won’t be visible to the naked eye until it flares. What we like to do is note when a faint satellite is set to pass by a bright star, then sit back with our trusty 15x 45 image-stabilized binoculars and watch. We caught sight of the ‘tool bag’ lost during an ISS EVA in 2009 in this fashion. There it was, drifting past Spica as a +7th magnitude ‘star’. The key to this method is an accurate prediction—Heavens-Above now overlays orbital satellite passes on all-sky charts—and an accurate time source. We prefer to have WWV radio running in the background, as it’ll call out the time signal so we don’t have to take our eyes off the sky.

Veteran satellite watcher Ted Molczan recently discussed the prospects for spotting LightSail once it’s deployed. “By then, the orbit will be visible from the northern hemisphere during the middle of the night. The southern hemisphere may have marginal evening passes. Note that the high area to mass ratio with the sail deployed, combined with the low perigee height, is expected to result in decay as soon as a couple days after deployment.”

Read a further discussion concerning OTV-4 and associated payloads by Mr. Molczan on the See-Sat message board here.

The Planetary Society’s Jason Davis confirmed for Universe Today that LightSail will deploy 28 days after launch. But we may only have a slim two day observation window for LightSail between deployment and reentry.

A deployment of LightSail 28 days after launch would put it in the June 16th timeframe.

“That’s the nominal mission time, yes,” Davis told Universe Today. “Our orbital models predict 2-10 days. For our 2016 flight, the mission will last at least four months.”

The Planetary Society plans to have a live ‘mission control center’ to track LightSail after P-POD deployment, complete with a Google Map showing pass predictions.

Satellite spotting can be a fun and addictive pastime, where part of the fun is sleuthing out what you’re seeing. Hey, some relics of space history such as the early Vanguards, Telstars, and Canada’s first satellite Alouette-1 are still up there! Nabbing these photographically are as simple as plopping your DSLR on a tripod, setting the focus and doing a time exposure as the satellite passes by.

Here’s to smooth solar sailing and clear skies as we embark on our quest to track down the X-37B and LightSail-1 in orbit.

-Follow us as @Astroguyz on Twitter, as we’ll be providing further info on orbits and visibility passes as they are made public.

Weekly Space Hangout – May 8, 2015: Emily Rice & Brian Levine from Astronomy on Tap

Host: Fraser Cain (@fcain)

Special Guest: Emily Rice & Brian Levine from Astronomy on Tap

Guests:

Jolene Creighton (@jolene723 / fromquarkstoquasars.com)

Charles Black (@charlesblack / sen.com/charles-black)

Brian Koberlein (@briankoberlein)

Dave Dickinson (@astroguyz / www.astroguyz.com)

Continue reading “Weekly Space Hangout – May 8, 2015: Emily Rice & Brian Levine from Astronomy on Tap”