The month of October is upon us this coming weekend, and with it, one of the better annual meteor showers is once again active: the Orionids.

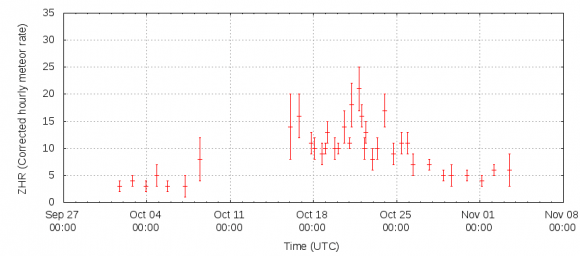

In 2016, the Orionid meteors are expected to peak on October 22nd at 2:00 UT (10:00 PM U.S. Eastern Time on October 21st) , favoring Europe and Africa in the early morning hours. The shower is active for a one month period from October 2nd to November 2nd, and can vary with a Zenithal Hourly Rate (ZHR) of 10-70 meteors per hour. This year, the Orionids are expected to produce a maximum ideal ZHR of 15-25 meteors per hour. The radiant of the Orionids is located near right ascension 6 hours 24 minutes, declination 15 degrees north at the time of the peak. The radiant is in the constellation of Orion very near its juncture with Gemini and Taurus.

The Moon is at a 55% illuminated, waning gibbous phase at the peak of the Orionids, making 2016 an unfavorable year for this shower, though that shouldn’t stop you from trying. It’s true that the Moon is only 19 degrees east of the radiant in the adjacent constellation Gemini at its peak on the key morning of October 22, though it’ll move farther on through the last week of October.

In previous recent years, the Orionids produced a Zenithal Hourly Rate (ZHR) of 20 (2014) and a ZHR of 30 (2013).

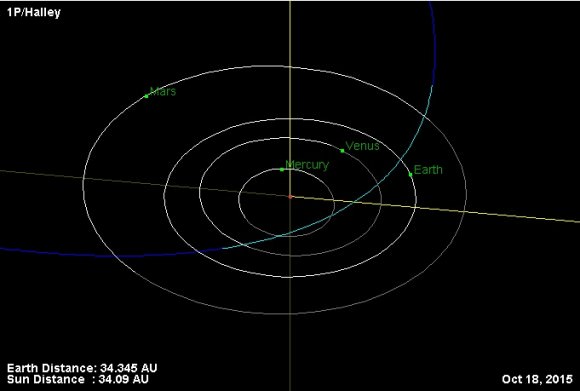

The Orionid meteors strike the Earth at a moderately fast velocity of 66 km/s, and the shower tends to produce a relatively high ratio of fireballs with an r value of = 2.5. The source of the Orionids is none other than renowned comet 1/P Halley. Halley last paid the inner solar system a visit in early 1986, and will once again reach perihelion on July 28, 2061. Let’s see, by then I’ll be…

Unlike most meteor showers, the Orionids display a very unpredictable maximum – many sources decline to put a precise date on the shower’s expected maximum at all. On some years, the Orionids barely top 10 per hour at their maximum, while on others they display a broad but defined peak. One 1982 study out of Czechoslovakia suggested a twin peak for this shower after looking at activity from 1944 to 1950. All good reasons to be vigilant for Orionids throughout the coming month of October.

And check out this brilliant meteor that lit up the skies over the southern UK this past weekend:

‘Tis the season for cometary dust particles to light up the night sky. Trace the path of a suspect meteor to the club of Orion, and you’ve likely sighted an Orionid meteor. But other showers showers are active in October, including:

The Draconids: Peaking around October 8th, these are debris shed by Comet 21P Giacobini-Zinner. The Draconids are prone to great outbursts, such as the 2011 and 2012 meteor storm, but are expected to yield a paltry ZHR of 10 in 2016.

The Taurids: Late October into early November is Taurid fireball season, peaking with a ZHR of 5 around October 10th (the Southern Taurids) and November 12th (the Northern Taurids).

The Camelopardalids: Another wildcard shower prone to periodic outbursts. 2016 is expected to be an off year for this shower, with a ZHR of 10 topping out on October 5.

And farther afield, we’ve got the Leonids (November 17th) the Geminids (December 14th) and the Ursids (December 22nd) to close out 2016.

Observing a meteor shower like the Orionids is as simple as finding a dark site with a clear horizon, laying back and watching via good old Mark-1 eyeball. Blocking that gibbous Moon behind a building or hill will also increase your chances of catching an Orionid. Expect rates to pick up toward dawn, as the Earth turns forward and plows headlong into the meteor stream.

You can make a count of what you see and report it to the International Meteor Organization which keeps regular tabs of meteor activity.

Photographing Orionids this year might be problematic, owing to the proximity of the bright Moon, though not impossible. Again, aiming at a wide quadrant of the sky opposite to the Moon might just nab a bright Orionid meteor in profile. We like to just set our camera’s intervalometer to take a sequence of 30” exposures of the sky, and let it do the work while we’re observing visually. Nearly every meteor we’ve caught photographically turned up in later review, a testament to the limits of visual observing.

Clear skies, good luck, and send those Orionid images in the Universe Today’s Flickr forum.