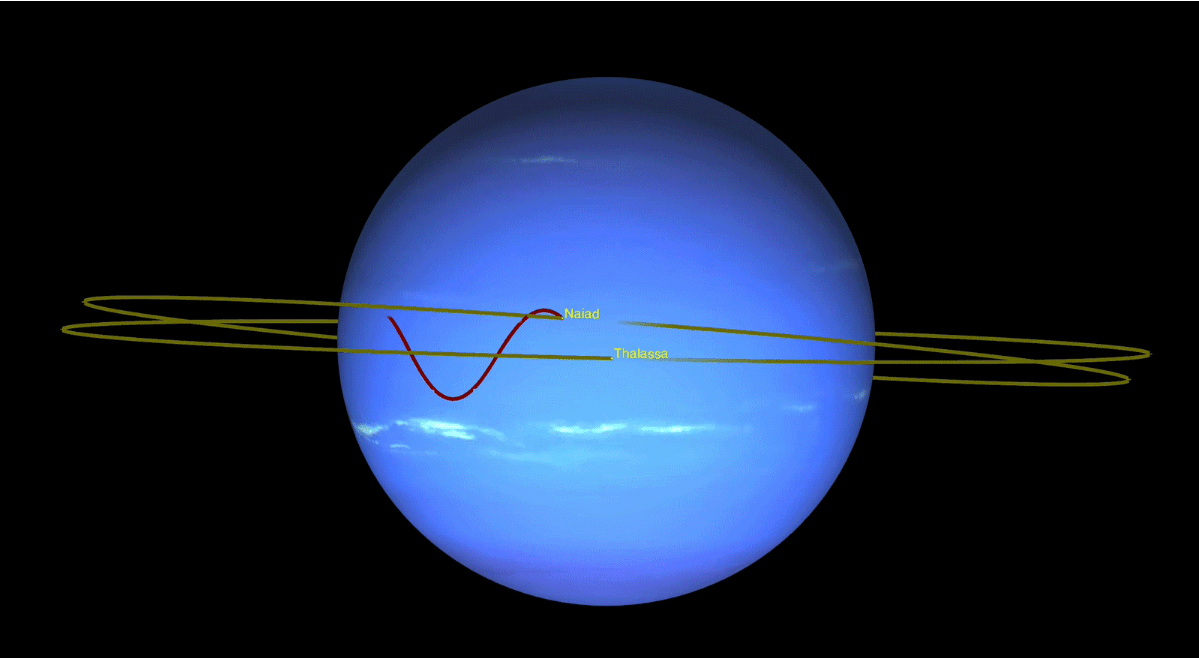

Like a long-married couple accustomed to each other’s kitchen habits, two of Neptune’s moons are masters at sharing space without colliding. And though both situations may appear odd to an observer, there’s a certain dance-like quality to them both.

Continue reading “Two of Neptune’s Moons Dance Around Each Other as they Orbit”NASA Wants to Send a Low-Cost Mission to Explore Neptune’s Moon Triton

In the coming years, NASA has some bold plans to build on the success of the New Horizons mission. Not only did this spacecraft make history by conducting the first-ever flyby of Pluto in 2015, it has since followed up on that by making the first encounter in history with a Kuiper Belt Object (KBO) – 2014 MU69 (aka. Ultima Thule).

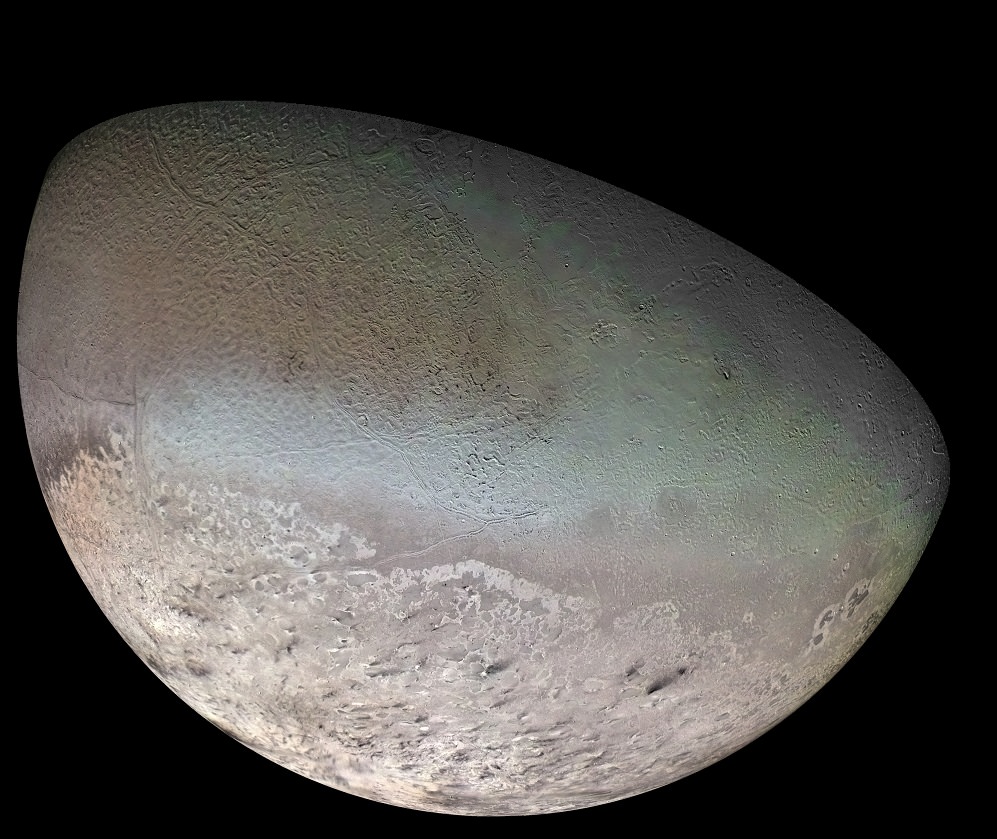

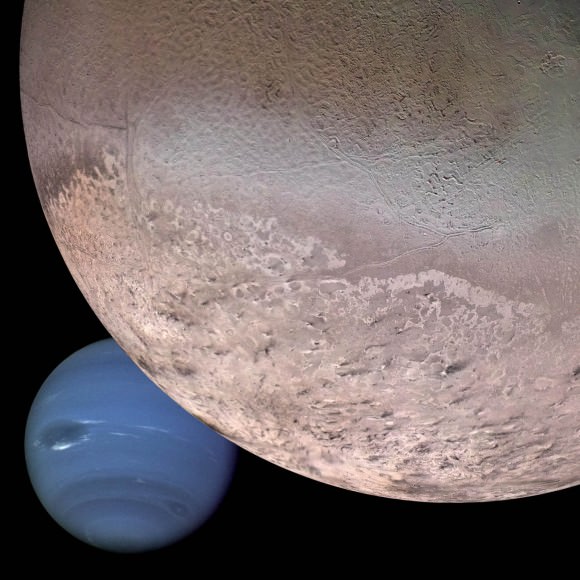

Given the wealth of data and stunning images that resulted from these events (which NASA scientists are still processing), other similarly-ambitious missions to explore the outer Solar System are being considered. For example, there is the proposal for the Trident spacecraft, a Discovery-class mission that would reveal things about Neptune’s largest moon, Triton.

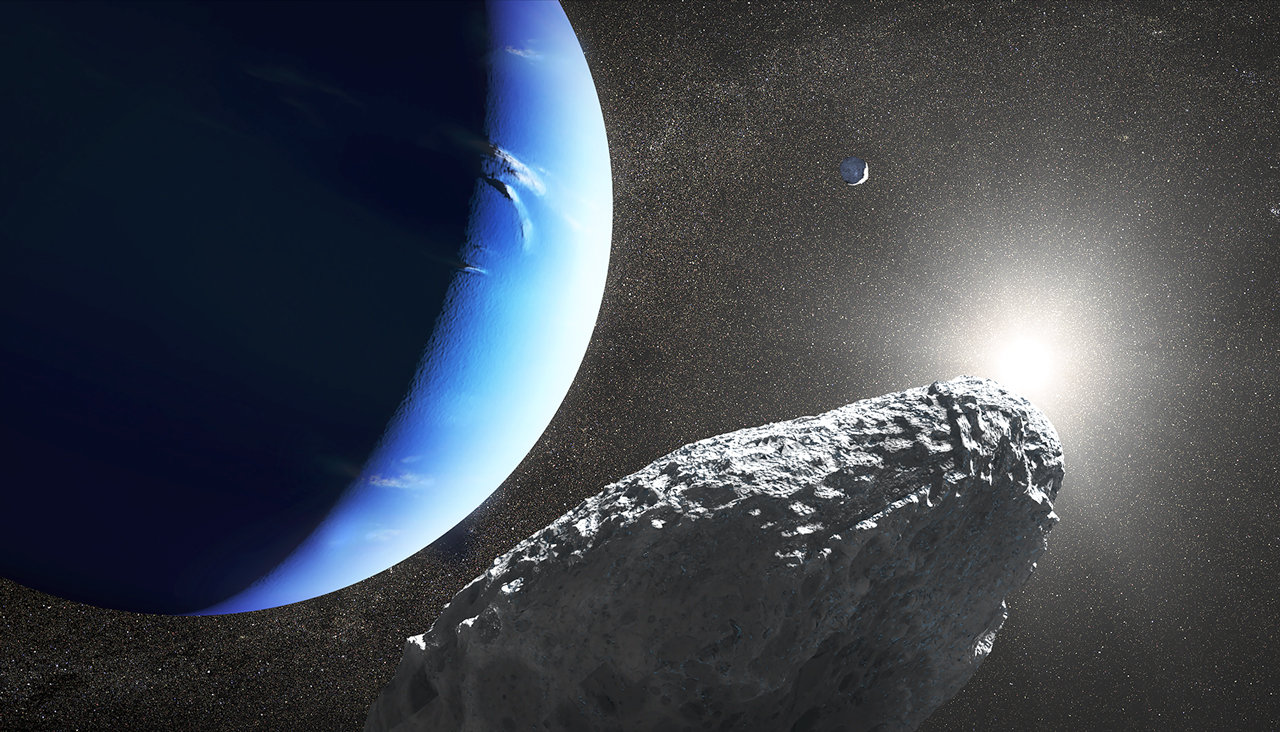

Continue reading “NASA Wants to Send a Low-Cost Mission to Explore Neptune’s Moon Triton”Say Hello to Hippocamp! The New Moon Discovered at Neptune, Which Could Have Broken off from the Larger Moon Proteus

Moons have the coolest names, don’t they? Proteus, Titan, and Callisto. Phobos, Deimos, and Encephalitis. But not Io. That’s a stupid name for a moon. There’s only two ways to pronounce it and we still get it wrong. Anyway, now we have another cool one: Hippocamp!

Okay, maybe the new name isn’t that cool. It sounds like a summer camp for overweight artiodactyls. But whatever. It’s not every day our Solar System gets a new moon.

Continue reading “Say Hello to Hippocamp! The New Moon Discovered at Neptune, Which Could Have Broken off from the Larger Moon Proteus”Hubble Shows off the Atmospheres of Uranus and Neptune

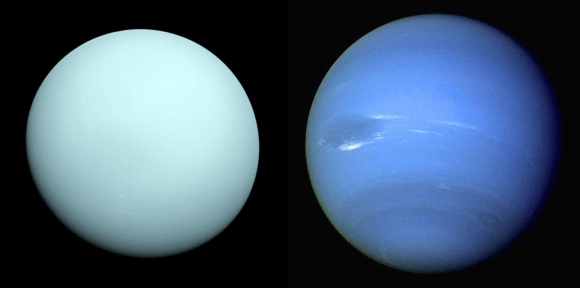

Like Earth, Uranus and Neptune have season and experience changes in weather patterns as a result. But unlike Earth, the seasons on these planets last for years rather than months, and weather patterns occur on a scale that is unimaginable by Earth standards. A good example is the storms that have been observed in Neptune and Uranus’ atmosphere, which include Neptune’s famous Great Dark Spot.

During its yearly routine of monitoring Uranus and Neptune, NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope (HST) recently provided updated observations of both planets’ weather patterns. In addition to spotting a new and mysterious storm on Neptune, Hubble provided a fresh look at a long-lived storm around Uranus’ north pole. These observations are part of Hubble‘s long-term mission to improve our understanding of the outer planets.

Continue reading “Hubble Shows off the Atmospheres of Uranus and Neptune”Exploring the Ice Giants: Neptune and Uranus at Opposition for 2018

Have you seen the outer ice giant planets for yourself?

This week is a good time to check the most difficult of the major planets off of your life list, as Neptune reaches opposition for 2018 on Friday, September 7th at at ~18:00 Universal Time (UT)/2:00 PM EDT. And while it may not look like much more than a gray-blue dot at the eyepiece, the outermost ice giant world has a fascinating tale to tell. Continue reading “Exploring the Ice Giants: Neptune and Uranus at Opposition for 2018”

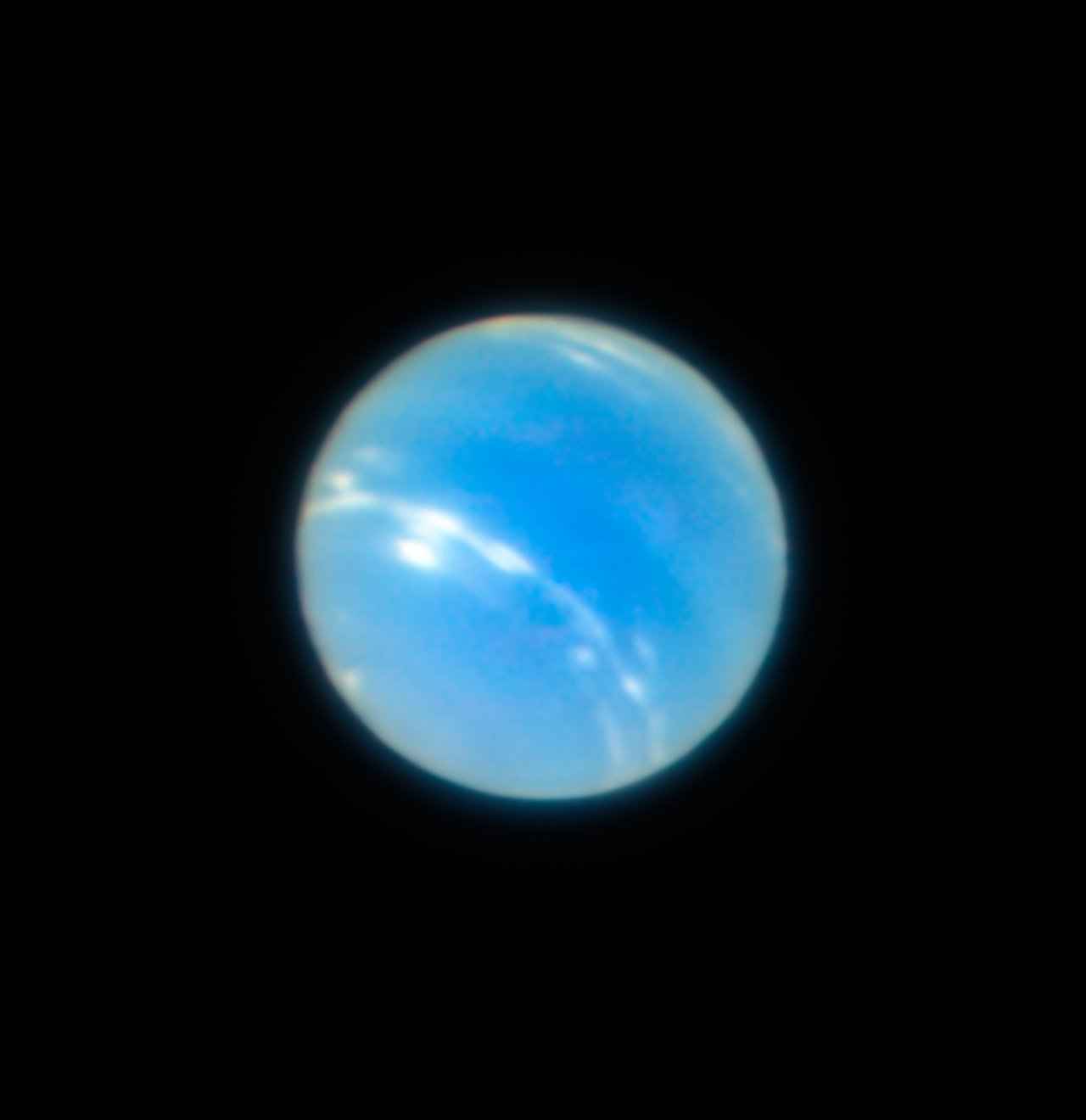

This is a Photo of Neptune, From the Ground! ESO’s New Adaptive Optics Makes Ground Telescopes Ignore the Earth’s Atmosphere

In 2007, the European Southern Observatory (ESO) completed work on the Very Large Telescope (VLT) at the Paranal Observatory in northern Chile. This ground-based telescope is the world’s most advanced optical instrument, consisting of four Unit Telescopes with main mirrors (measuring 8.2 meters in diameter) and four movable 1.8-meter diameter Auxiliary Telescopes.

Recently, the VLT was upgraded with a new instrument known as the Multi Unit Spectroscopic Explorer (MUSE), a panoramic integral-field spectrograph that works at visible wavelengths. Thanks to the new adaptive optics mode that this allows for (known as laser tomography) the VLT was able to recently acquire some images of Neptune, star clusters and other astronomical objects with impeccable clarity.

In astronomy, adaptive optics refers to a technique where instruments are able to compensate for the blurring effect caused by Earth’s atmosphere, which is a serious issue when it comes to ground-based telescopes. Basically, as light passes through our atmosphere, it becomes distorted and causes distant objects to become blurred (which is why stars appear to twinkle when seen with the naked eye).

One solution to this problem is to deploy telescopes into space, where atmospheric disturbance is not an issue. Another is to rely on advanced technology that can artificially correct for the distortions, thus resulting in much clearer images. One such technology is the MUSE instrument, which works with an adaptive optics unit called a GALACSI – a subsystem of the Adaptive Optics Facility (AOF).

The instrument allows for two adaptive optics modes – the Wide Field Mode and the Narrow Field Mode. Whereas the former corrects for the effects of atmospheric turbulence up to one km above the telescope over a comparatively wide field of view, the Narrow Field mode uses laser tomography to correct for almost all of the atmospheric turbulence above the telescope to create much sharper images, but over a smaller region of the sky.

This consists of four lasers that are fixed to the fourth Unit Telescope (UT4) beaming intense orange light into the sky, simulating sodium atoms high in the atmosphere and creating artificial “Laser Guide Stars”. Light from these artificial stars is then used to determine the turbulence in the atmosphere and calculate corrections, which are then sent to the deformable secondary mirror of the UT4 to correct for the distorted light.

Using this Narrow Field Mode, the VLT was able to capture remarkably sharp test images of the planet Neptune, distant star clusters (such as the globular star cluster NGC 6388), and other objects. In so doing, the VLT demonstrated that its UT4 mirror is able to reach the theoretical limit of image sharpness and is no longer limited by the effects of atmospheric distortion.

This essentially means that it is now possible for the VLT to capture images from the ground that are sharper than those taken by the Hubble Space Telescope. The results from UT4 will also help engineers to make similar adaptations to the ESO’s Extremely Large Telescope (ELT), which will also rely on laser tomography to conduct its surveys and accomplish its scientific goals.

These goals include the study of supermassive black holes (SMBHs) at the centers of distant galaxies, jets from young stars, globular clusters, supernovae, the planets and moons of the Solar System, and extra-solar planets. In short, the use of adaptive optics – as tested and confirmed by the VLT’s MUSE – will allow astronomers to use ground-based telescopes to study the properties of astronomical objects in much greater detail than ever before.

In addition, other adaptive optics systems will benefit from work with the Adaptive Optics Facility (AOF) in the coming years. These include the ESO’s GRAAL, a ground layer adaptive optics module that is already being used by the Hawk-I infrared wide-field imager. In a few years, the powerful Enhanced Resolution Imager and Spectrograph (ERIS) instrument will also be added to the VLT.

Between these upgrades and the deployment of next-generation space telescopes in the coming years (like the James Webb Space Telescope, which will be deploying in 2021), astronomers expect to bringing a great deal more of the Universe “into focus”. And what they see is sure to help resolve some long-standing mysteries, and will probably create a whole lot more!

And be sure to enjoy these videos of the images obtained by the VLT of Neptune and NGC 6388, courtesy of the ESO:

Further Reading: ESO

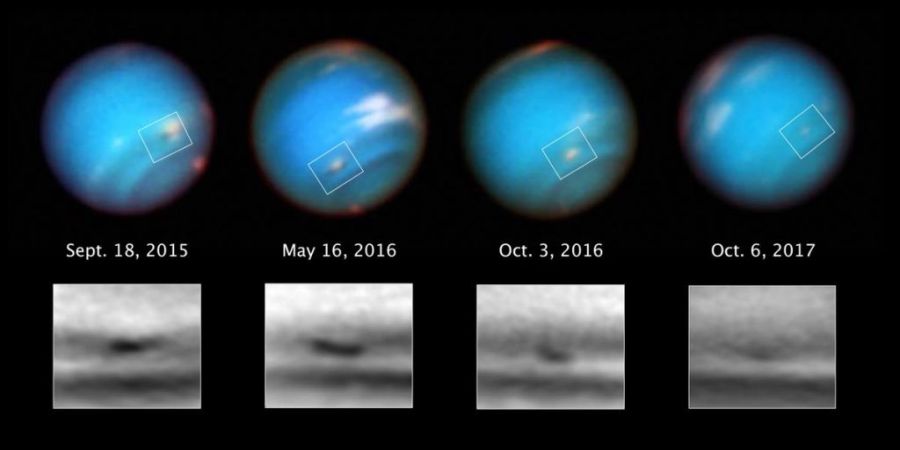

Neptune’s Huge Storm Is Shrinking Away In New Images From Hubble

Back in the late 1980’s, Voyager 2 was the first spacecraft to capture images of the giant storms in Neptune’s atmosphere. Before then, little was known about the deep winds cycling through Neptune’s atmosphere. But Hubble has been turning its sharp eye towards Neptune over the years to study these storms, and over the past couple of years, it’s watched one enormous storm petering out of existence.

“It looks like we’re capturing the demise of this dark vortex, and it’s different from what well-known studies led us to expect.” – Michael H. Wong, University of California at Berkeley.

When we think of storms on the other planets in our Solar System, we automatically think of Jupiter. Jupiter’s Great Red Spot is a fixture in our Solar System, and has lasted 200 years or more. But the storms on Neptune are different: they’re transient.

The storm on Neptune moves in an anti-cyclonic direction, and if it were on Earth, it would span from Boston to Portugal. Neptune has a much deeper atmosphere than Earth—in fact it’s all atmosphere—and this storm brings up material from deep inside. This gives scientists a chance to study the depths of Neptune’s atmosphere without sending a spacecraft there.

The first question facing scientists is ‘What is the storm made of?’ The best candidate is a chemical called hydrogen sulfide (H2S). H2S is a toxic chemical that stinks like rotten eggs. But particles of H2S are not actually dark, they’re reflective. Joshua Tollefson from the University of California at Berkeley, explains: “The particles themselves are still highly reflective; they are just slightly darker than the particles in the surrounding atmosphere.”

“We have no evidence of how these vortices are formed or how fast they rotate.” – Agustín Sánchez-Lavega, University of the Basque Country in Spain.

But beyond guessing what chemical the spot might me made of, scientists don’t know much else. “We have no evidence of how these vortices are formed or how fast they rotate,” said Agustín Sánchez-Lavega from the University of the Basque Country in Spain. “It is most likely that they arise from an instability in the sheared eastward and westward winds.”

There’ve been predictions about how storms on Neptune should behave, based on work done in the past. The expectation was that storms like this would drift toward the equator, then break up in a burst of activity. But this dark storm is on its own path, and is defying expectations.

“We thought that once the vortex got too close to the equator, it would break up and perhaps create a spectacular outburst of cloud activity.” – Michael H. Wong, University of California at Berkeley.

“It looks like we’re capturing the demise of this dark vortex, and it’s different from what well-known studies led us to expect,” said Michael H. Wong of the University of California at Berkeley, referring to work by Ray LeBeau (now at St. Louis University) and Tim Dowling’s team at the University of Louisville. “Their dynamical simulations said that anticyclones under Neptune’s wind shear would probably drift toward the equator. We thought that once the vortex got too close to the equator, it would break up and perhaps create a spectacular outburst of cloud activity.”

Rather than going out in some kind of notable burst of activity, this storm is just fading away. And it’s also not drifting toward the equator as expected, but is making its way toward the south pole. Again, the inevitable comparison is with Jupiter’s Great Red Spot (GRS).

The GRS is held in place by the prominent storm bands in Jupiter’s atmosphere. And those bands move in alternating directions, constraining the movement of the GRS. Neptune doesn’t have those bands, so it’s thought that storms on Neptune would tend to drift to the equator, rather than toward the south pole.

This isn’t the first time that Hubble has been keeping an eye on Neptune’s storms. The Space Telescope has also looked at storms on Neptune in 1994 and 1996. The video below tells the story of Hubble’s storm watching mission.

The images of Neptune’s storms are from the Hubble Outer Planets Atmosphere Legacy (OPAL) program. OPAL gathers long-term baseline images of the outer planets to help us understand the evolution and atmospheres of the gas giants. Images of Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus and Neptune are being taken with a variety of filters to form a kind of time-lapse database of atmospheric activity on the four gas planets.

Triton’s Arrival was Chaos for the Rest of Neptune’s Moons

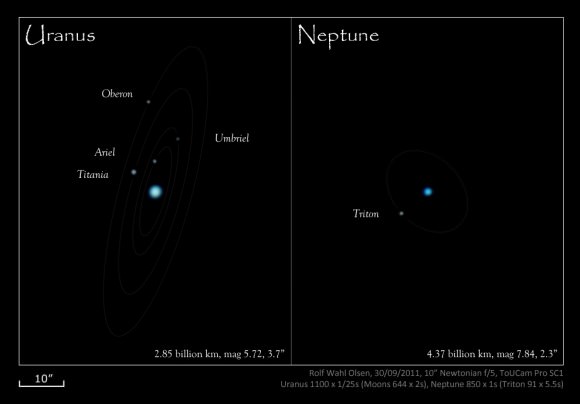

The study of the Solar System’s many moons has revealed a wealth of information over the past few decades. These include the moons of Jupiter – 69 of which have been identified and named – Saturn (which has 62) and Uranus (27). In all three cases, the satellites that orbit these gas giants have prograde, low-inclination orbits. However, within the Neptunian system, astronomers noted that the situation was quite different.

Compared to the other gas giants, Neptune has far fewer satellites, and most of the system’s mass is concentrated within a single satellite that is believed to have been captured (i.e. Triton). According to a new study by a team from the Weizmann Institute of Science in Israel and the Southwest Research Institute (SwRI) in Boulder, Colorado, Neptune may have once had a more massive systems of satellites, which the arrival of Triton may have disrupted.

The study, titled “Triton’s Evolution with a Primordial Neptunian Satellite System“, recently appeared in The Astrophysical Journal. The research team consisted of Raluca Rufu, an astrophysicist and geophysicist from the Weizmann Institute, and Robin M. Canup – the Associate VP of the SwRI. Together, they considered models of a primordial Neptunian system, and how it may have changed thanks to the arrival of Triton.

For many years, astronomers have been of the opinion that Triton was once a dwarf planet that was kicked out of the Kuiper Belt and captured by Neptune’s gravity. This is based on its retrograde and highly-inclined orbit (156.885° to Neptune’s equator), which contradicts current models of how gas giants and their satellites form. These models suggest that as giant planets accrete gas, their moons form from a surrounding debris disk.

Consistent with the other gas giants, the largest of these satellites would have prograde, regular orbits that are not particularly inclined relative to their planet’s equator (typically less than 1°). In this respect, Triton is believed to have once been part of a binary made up of two Trans-Neptunian Objects (TNOs). When they swung past Neptune, Triton would have been captured by its gravity and gradually fell into its current orbit.

As Dr. Rufu and Dr. Canup state in their study, the arrival of this massive satellite would have likely caused a lot of disruption in the Neptunian system and affected its evolution. This consisted of them exploring how interactions – like scattering or collisions – between Triton and Neptune’s prior satellites would have modified Triton’s orbit and mass, as well as the system at large. As they explain:

“We evaluate whether the collisions among the primordial satellites are disruptive enough to create a debris disk that would accelerate Triton’s circularization, or whether Triton would experience a disrupting impact first. We seek to find the mass of the primordial satellite system that would yield the current architecture of the Neptunian system.”

To test how the Neptunian system could have evolved, they considered different types of primordial satellite systems. This included one that was consistent with Uranus’ current system, made up of prograde satellites with a similar mass ration as Uranus’ largest moons – Ariel, Umbriel, Titania and Oberon – as well as one that was either more or less massive. They then conducted simulations to determine how Triton’s arrival would have altered these systems.

These simulations were based on disruption scaling laws which considered how non-hit-and-run impacts between Triton and other bodies would have led to a redistribution of matter in the system. What they found, after 200 simulations, was that a system that had a mass ratio that was similar to the current Uranian system (or smaller) would have been most likely to produce the current Neptunian system. As they state:

“We find that a prior satellite system with a mass ratio similar to the Uranian system or smaller has a substantial likelihood of reproducing the current Neptunian system, while a more massive system has a low probability of leading to the current configuration.”

They also found that the interaction of Triton with an earlier satellite system also offers a potential explanation for how its initial orbit could have been decreased fast enough to preserve the orbits of small irregular satellites. These Nereid-like bodies would have otherwise been kicked out of their orbits as tidal forces between Neptune and Triton caused Triton to assume its current orbit.

Ultimately, this study not only offers a possible explanation as to why Neptune’s system of satellites differs from those of other gas giants; it also indicates that Neptune’s proximity to the Kuiper Belt is what is responsible. At one time, Neptune may have had a system of moons that were very much like those of Jupiter, Saturn, and Uranus. But since it is well-situated to pick up dwarf planet-sized objects that were kicked out of the Kuiper Belt, this changed.

Looking to the future, Rufu and Canup indicate that additional studies are needed in order to shed light on Triton’s early evolution as a Neptunian satellite. Essentially, there are still unanswered questions concerning the effects the system of pre-existing satellites had on Triton, and how stable its irregular prograde satellites were.

These findings were also presented by Dr, Rufu and Dr. Canup during the 48th Lunar and Planetary Science Conference, which took place in The Woodlands, Texas, this past March.

Further Reading: The Astronomical Journal, USRA

Hallelujah, It’s Raining Diamonds! Just like the Insides of Uranus and Neptune.

For more than three decades, the internal structure and evolution of Uranus and Neptune has been a subject of debate among scientists. Given their distance from Earth and the fact that only a few robotic spacecraft have studied them directly, what goes on inside these ice giants is still something of a mystery. In lieu of direct evidence, scientists have relied on models and experiments to replicate the conditions in their interiors.

For instance, it has been theorized that within Uranus and Neptune, the extreme pressure conditions squeeze hydrogen and carbon into diamonds, which then sink down into the interior. Thanks to an experiment conducted by an international team of scientists, this “diamond rain” was recreated under laboratory conditions for the first time, giving us the first glimpse into what things could be like inside ice giants.

The study which details this experiment, titled “Formation of Diamonds in Laser-Compressed Hydrocarbons at Planetary Interior Conditions“, recently appeared in the journal Nature Astronomy. Led by Dr. Dominik Kraus, a physicist from the Helmholtz-Zentrum Dresden-Rossendorf Institute of Radiation Physics, the team included members from the SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory, the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory and UC Berkeley.

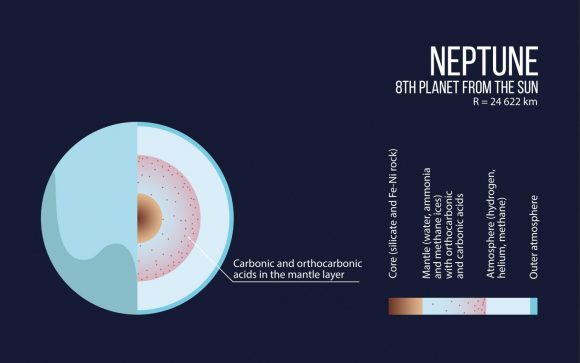

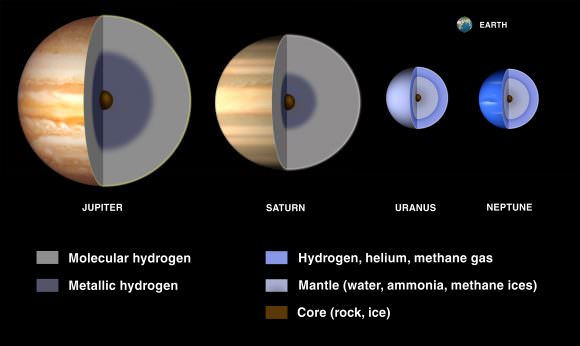

For decades, scientists have held that the interiors of planets like Uranus and Neptune consist of solid cores surrounded by a dense concentrations of “ices”. In this case, ice refers to hydrogen molecules connected to lighter elements (i.e. as carbon, oxygen and/or nitrogen) to create compounds like water and ammonia. Under extreme pressure conditions, these compounds become semi-solid, forming “slush”.

And at roughly 10,000 kilometers (6214 mi) beneath the surface of these planets, the compression of hydrocarbons is thought to create diamonds. To recreate these conditions, the international team subjected a sample of polystyrene plastic to two shock waves using an intense optical laser at the Matter in Extreme Conditions (MEC) instrument, which they then paired with x-ray pulses from the SLAC’s Linac Coherent Light Source (LCLS).

As Dr. Kraus, the head of a Helmholtz Young Investigator Group at HZDR, explained in an HZDR press release:

“So far, no one has been able to directly observe these sparkling showers in an experimental setting. In our experiment, we exposed a special kind of plastic – polystyrene, which also consists of a mix of carbon and hydrogen – to conditions similar to those inside Neptune or Uranus.”

The plastic in this experiment simulated compounds formed from methane, a molecule that consists of one carbon atom bound to four hydrogen atoms. It is the presence of this compound that gives both Uranus and Neptune their distinct blue coloring. In the intermediate layers of these planets, it also forms hydrocarbon chains that are compressed into diamonds that could be millions of karats in weight.

The optical laser the team employed created two shock waves which accurately simulated the temperature and pressure conditions at the intermediate layers of Uranus and Neptune. The first shock was smaller and slower, and was then overtaken by the stronger second shock. When they overlapped, the pressure peaked and tiny diamonds began to form. At this point, the team probed the reactions with x-ray pulses from the LCLS.

This technique, known as x-ray diffraction, allowed the team to see the small diamonds form in real-time, which was necessary since a reaction of this kind can only last for fractions of a second. As Siegfried Glenzer, a professor of photon science at SLAC and a co-author of the paper, explained:

“For this experiment, we had LCLS, the brightest X-ray source in the world. You need these intense, fast pulses of X-rays to unambiguously see the structure of these diamonds, because they are only formed in the laboratory for such a very short time.”

In the end, the research team found that nearly every carbon atom in the original plastic sample was incorporated into small diamond structures. While they measured just a few nanometers in diameter, the team predicts that on Uranus and Neptune, the diamonds would be much larger. Over time, they speculate that these could sink into the planets’ atmospheres and form a layer of diamond around the core.

In previous studies, attempts to recreate the conditions in Uranus and Neptune’s interior met with limited success. While they showed results that indicated the formation of graphite and diamonds, the teams conducting them could not capture the measurements in real-time. As noted, the extreme temperatures and pressures that exist within gas/ice giants can only be simulated in a laboratory for very short periods of time.

However, thanks to LCLS – which creates X-ray pulses a billion times brighter than previous instruments and fires them at a rate of about 120 pulses per second (each one lasting just quadrillionths of a second) – the science team was able to directly measure the chemical reaction for the first time. In the end, these results are of particular significance to planetary scientists who specialize in the study of how planets form and evolve.

As Kraus explained, it could cause to rethink the relationship between a planet’s mass and its radius, and lead to new models of planet classification:

“With planets, the relationship between mass and radius can tell scientists quite a bit about the chemistry. And the chemistry that happens in the interior can provide additional information about some of the defining features of the planet… We can’t go inside the planets and look at them, so these laboratory experiments complement satellite and telescope observations.”

This experiment also opens new possibilities for matter compression and the creation of synthetic materials. Nanodiamonds currently have many commercial applications – i.e. medicine, electronics, scientific equipment, etc, – and creating them with lasers would be far more cost-effective and safe than current methods (which involve explosives).

Fusion research, which also relies on creating extreme pressure and temperature conditions to generate abundant energy, could also benefit from this experiment. On top of that, the results of this study offer a tantalizing hint at what the cores of massive planets look like. In addition to being composed of silicate rock and metals, ice giants may also have a diamond layer at their core-mantle boundary.

Assuming we can create probes of sufficiently strong super-materials someday, wouldn’t that be worth looking into?

Further Reading: SLAC, HZDR, Nature Astronomy

What are Gas Giants?

Between the planets of the inner and outer Solar System, there are some stark differences. The planets that resides closer to the Sun are terrestrial (i.e. rocky) in nature, meaning that they are composed of silicate minerals and metals. Beyond the Asteroid Belt, however, the planets are predominantly composed of gases, and are much larger than their terrestrial peers.

This is why astronomers use the term “gas giants” when referring to the planets of the outer Solar System. The more we’ve come to know about these four planets, the more we’ve come to understand that no two gas giants are exactly alike. In addition, ongoing studies of planets beyond our Solar System (aka. “extra-solar planets“) has shown that there are many types of gas giants that do not conform to Solar examples. So what exactly is a “gas giant”?

Definition and Classification:

By definition, a gas giant is a planet that is primarily composed of hydrogen and helium. The name was originally coined in 1952 by James Blish, a science fiction writer who used the term to refer to all giant planets. In truth, the term is something of a misnomer, since these elements largely take a liquid and solid form within a gas giant, as a result of the extreme pressure conditions that exist within the interior.

What’s more, gas giants are also thought to have large concentrations of metal and silicate material in their cores. Nevertheless, the term has remained in popular usage for decades and refers to all planets – be they Solar or extra-solar in nature – that are composed mainly of gases. It is also in keeping with the practice of planetary scientists, who use a shorthand – i.e. “rock”, “gas”, and “ice” – to classify planets based on the most common element within them.

Hence the difference between Jupiter and Saturn on the one and, and Uranus and Neptune on the other. Due to the high concentrations of volatiles (such as water, methane and ammonia) within the latter two – which planetary scientists classify as “ices” – these two giant planets are often called “ice giants”. But since they are composed mainly of hydrogen and helium, they are still considered gas giants alongside Jupiter and Saturn.

Classification:

Today, Gas giants are divided into five classes, based on the classification scheme proposed by David Sudarki (et al.) in a 2000 study. Titled “Albedo and Reflection Spectra of Extrasolar Giant Planets“, Sudarsky and his colleagues designated five different types of gas giant based on their appearances and albedo, and how this is affected by their respective distances from their star.

Class I: Ammonia Clouds – this class applies to gas giants whose appearances are dominated by ammonia clouds, and which are found in the outer regions of a planetary system. In other words, it applies only to planets that are beyond the “Frost Line”, the distance in a solar nebula from the central protostar where volatile compounds – i.e. water, ammonia, methane, carbon dioxide, carbon monoxide – condense into solid ice grains.

Class II: Water Clouds – this applies to planets that have average temperatures typically below 250 K (-23 °C; -9 °F), and are therefore too warm to form ammonia clouds. Instead, these gas giants have clouds that are formed from condensed water vapor. Since water is more reflective than ammonia, Class II gas giants have higher albedos.

Class III: Cloudless – this class applies to gas giants that are generally warmer – 350 K (80 °C; 170 °F) to 800 K ( 530 °C; 980 °F) – and do not form cloud cover because they lack the necessary chemicals. These planets have low albedos since they do not reflect as much light into space. These bodies would also appear like clear blue globes because of the way methane in their atmospheres absorbs light (like Uranus and Neptune).

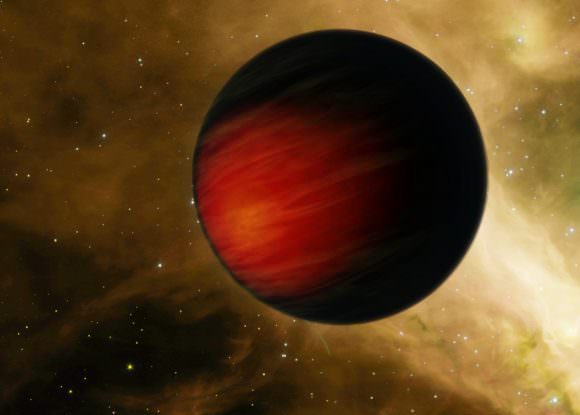

Class IV: Alkali Metals – this class of planets experience temperatures in excess of 900 K (627 °C; 1160 °F), at which point Carbon Monoxide becomes the dominant carbon-carrying molecule in their atmospheres (rather than methane). The abundance of alkali metals also increases substantially, and cloud decks of silicates and metals form deep in their atmospheres. Planets belonging to Class IV and V are referred to as “Hot Jupiters”.

Class V: Silicate Clouds – this applies to the hottest of gas giants, with temperatures above 1400 K (1100 °C; 2100 °F), or cooler planets with lower gravity than Jupiter. For these gas giants, the silicate and iron cloud decks are believed to be high up in the atmosphere. In the case of the former, such gas giants are likely to glow red from thermal radiation and reflected light.

Exoplanets:

The study of exoplanets has also revealed a wealth of other types of gas giants that are more massive than the Solar counterparts (aka. Super-Jupiters) as well as many that are comparable in size. Other discoveries have been a fraction of the size of their solar counterparts, while some have been so massive that they are just shy of becoming a star. However, given their distance from Earth, their spectra and albedo have cannot always be accurately measured.

As such, exoplanet-hunters tend to designate extra-solar gas giants based on their apparent sizes and distances from their stars. In the case of the former, they are often referred to as “Super-Jupiters”, Jupiter-sized, and Neptune-sized. To date, these types of exoplanet account for the majority of discoveries made by Kepler and other missions, since their larger sizes and greater distances from their stars makes them the easiest to detect.

In terms of their respective distances from their sun, exoplanet-hunters divide extra-solar gas giants into two categories: “cold gas giants” and “hot Jupiters”. Typically, cold hydrogen-rich gas giants are more massive than Jupiter but less than about 1.6 Jupiter masses, and will only be slightly larger in volume than Jupiter. For masses above this, gravity will cause the planets to shrink.

Exoplanet surveys have also turned up a class of planet known as “gas dwarfs”, which applies to hydrogen planets that are not as large as the gas giants of the Solar System. These stars have been observed to orbit close to their respective stars, causing them to lose atmospheric mass faster than planets that orbit at greater distances.

For gas giants that occupy the mass range between 13 to 75-80 Jupiter masses, the term “brown dwarf” is used. This designation is reserved for the largest of planetary/substellar objects; in other words, objects that are incredibly large, but not quite massive enough to undergo nuclear fusion in their core and become a star. Below this range are sub-brown dwarfs, while anything above are known as the lightest red dwarf (M9 V) stars.

Like all things astronomical in nature, gas giants are diverse, complex, and immensely fascinating. Between missions that seek to examine the gas giants of our Solar System directly to increasingly sophisticated surveys of distant planets, our knowledge of these mysterious objects continues to grow. And with that, so is our understanding of how star systems form and evolve.

We have written many interesting articles about gas giants here at Universe Today. Here’s The Planet Jupiter, The Planet Saturn, The Planet Uranus, The Planet Neptune, What are the Jovian Planets?, What are the Outer Planets of the Solar System?, What’s Inside a Gas Giant?, and Which Planets Have Rings?

For more information, check out NASA’s Solar System Exploration.

Astronomy Cast also has some great episodes on the subject. Here’s Episode 56: Jupiter to get you started!

Sources: