With just 12 days before Comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko reaches perihelion, we get a look at recent images and results released by the European Space Agency from the Philae lander along with spectacular 3D photos from Rosetta’s high resolution camera.

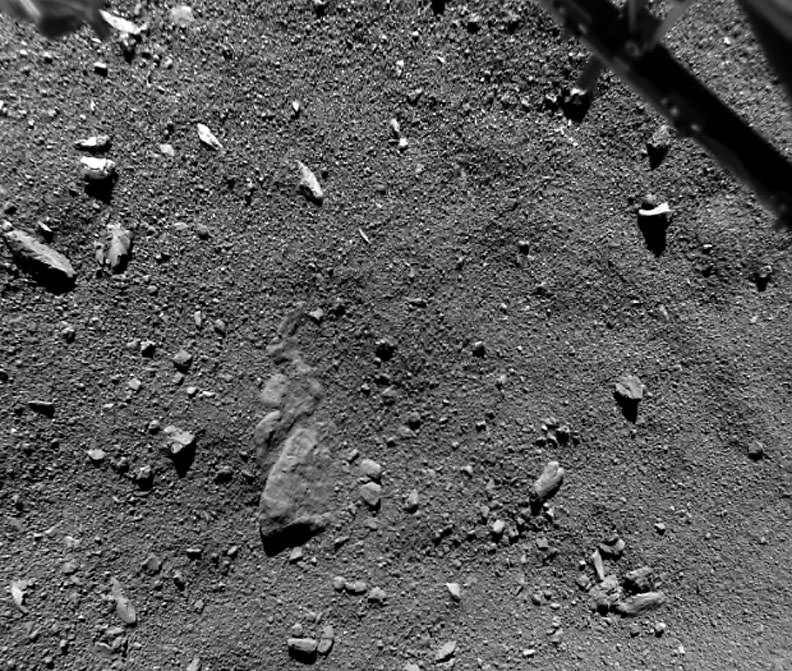

Credits: ESA/Rosetta/Philae/ROLIS/DLR

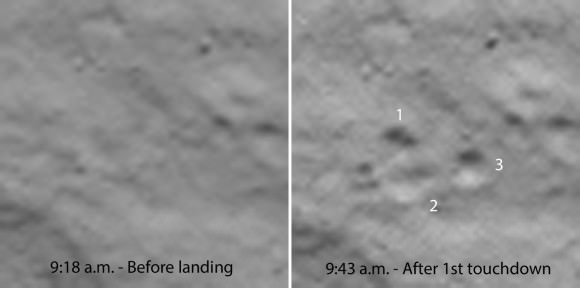

Remarkably, some 80% of the first science sequence was completed in the 64 hours before Philae fell into hibernation. Although unintentional, the failed landing attempt led to the unexpected bonus of getting data from two collection sites — the planned touchdown at Agilkia and its current precarious location at Abydos.

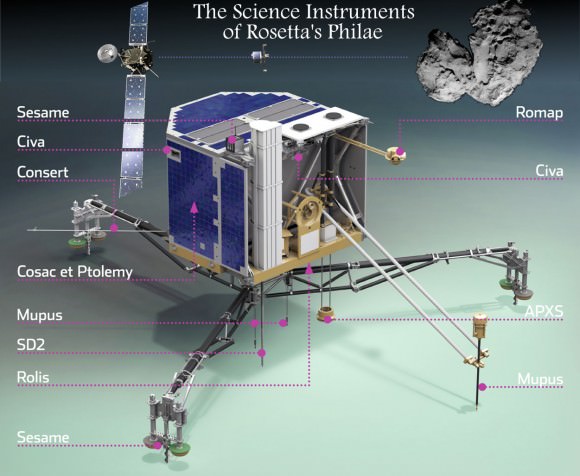

After first touching down, Philae was able to use its gas-sniffing Ptolemy and COSAC instruments to determine the makeup of the comet’s atmosphere and surface materials. COSAC analyzed samples that entered tubes at the bottom of the lander and found ice-poor dust grains that were rich in organic compounds containing carbon and nitrogen. It found 16 in all including methyl isocyanate, acetone, propionaldehyde and acetamide that had never been seen in comets before.

While you and I may not be familiar with some of these organics, their complexity hints that even in the deep cold and radiation-saturated no man’s land of outer space, a rich assortment of organic materials can evolve. Colliding with Earth during its early history, comets may have delivered chemicals essential for the evolution of life.

Ptolemy sampled the atmosphere entering tubes at the top of the lander and identified water vapor, carbon monoxide and carbon dioxide, along with smaller amounts of carbon-bearing organic compounds, including formaldehyde. Some of these juicy organic delights have long been thought to have played a role in life’s origins. Formaldehyde reacts with other commonly available materials to form complex sugars like ribose which forms the backbone of RNA and is related to the sugar deoxyribose, the “D” in DNA.

ROLIS (Rosetta Lander Imaging System) images taken shortly before the first touchdown revealed a surface of 3-foot-wide (meter-size) irregular-shaped blocks and coarse “soil” or regolith covered in “pebbles” 4-20 inches (10–50 cm) across as well as a mix of smaller debris.

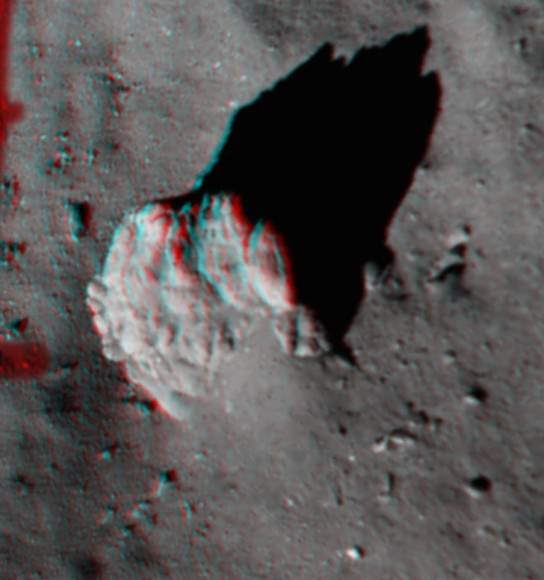

Agilkia’s regolith, the name given to the rocky soil of other planets, moons, comets and asteroids, is thought to extend to a depth of about 6 feet (2 meters) in places, but seems to be free from fine-grained dust deposits at the resolution of the images. The 16-foot-high boulder in the photo above has been heavily fractured by some type of erosional process, possibly a heating and cooling cycle that vaporized a portion of its ice. Dust from elsewhere on the comet has been transported to the boulder’s base. This appears to happen over much of 67P/C-G as jets shoot gas and dust into the coma, some of which then settles out across the comet’s surface.

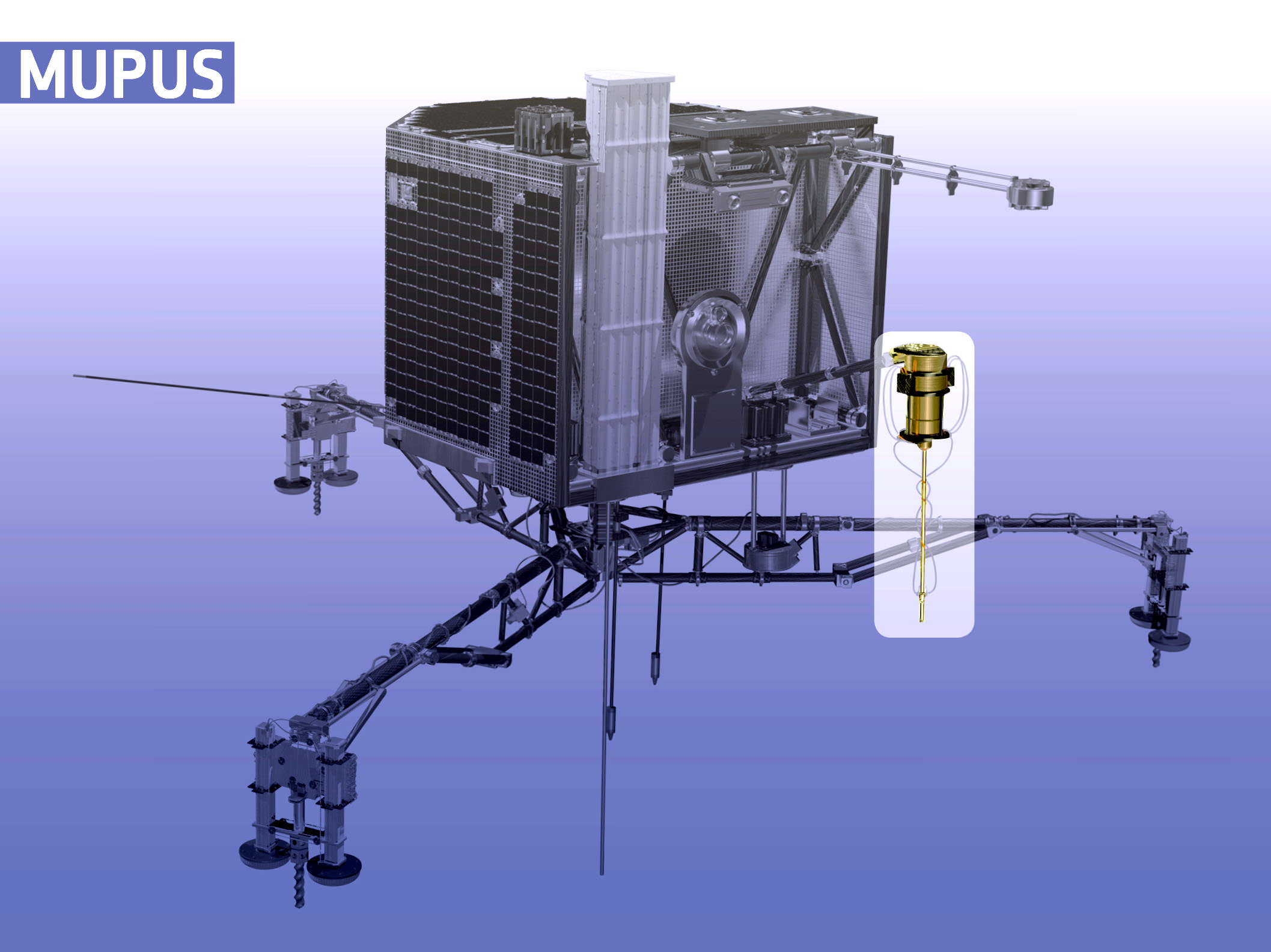

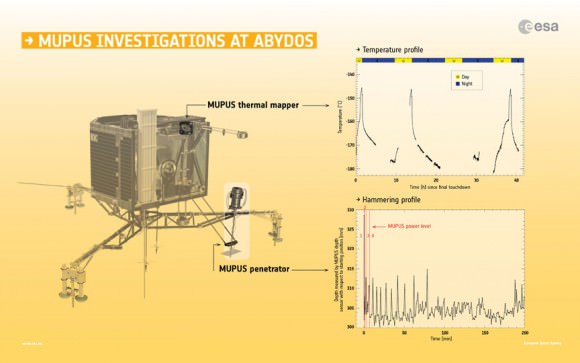

Another suite of instruments called MUPUS used a penetrating “hammer” to reveal a thin layer of dust about an inch thick (~ 3 cm) overlying a much harder, compacted mixture of dust and ice at Abydos. The thermal sensor took the comet’s daily temperature which varies from a high around –229° F (–145ºC) to a nighttime low of about –292° F (–180ºC), in sync with the comet’s 12.4 hour day. The rate at which the temperature rises and falls also indicates a thin layer of dust rests atop a compacted dust-ice crust.

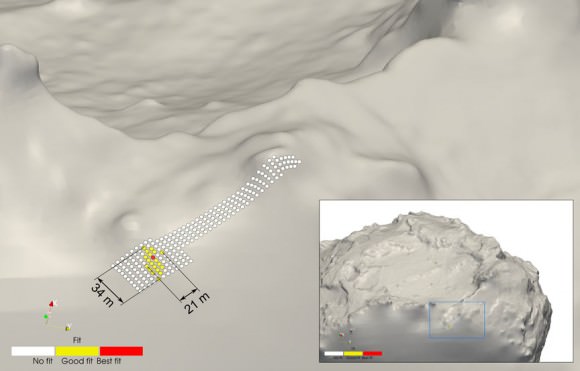

CONSERT, which passed radio waves through the nucleus between the lander and the orbiter, showed that the small lobe of the comet is a very loosely compacted mixture of dust and ice with a porosity of 75-85%, about that of lightly compacted snow. CONSERT was also used to help triangulate Philae’s location on the surface, nailing it down to an area just 69 x 112 feet ( 21 x 34 m) wide.

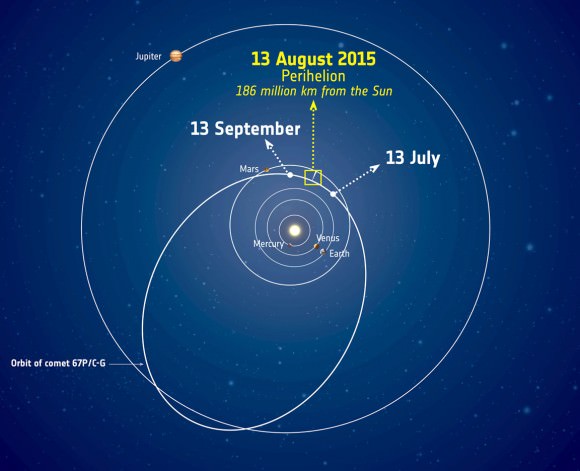

In fewer than two weeks, the comet will reach perihelion, its closest approach to the Sun at 116 million miles (186 million km), and the time when it will be most active. Rosetta will continue to monitor 67P C-G from a safe distance to lessen the chance an errant chunk of comet ice or dust might damage its instruments. Otherwise it’s business as usual. Activity will gradually decline after perihelion with Rosetta providing a ringside seat throughout. The best time for viewing the comet from Earth will be mid-month when the Moon is out of the morning sky. Watch for an article with maps and directions soon.

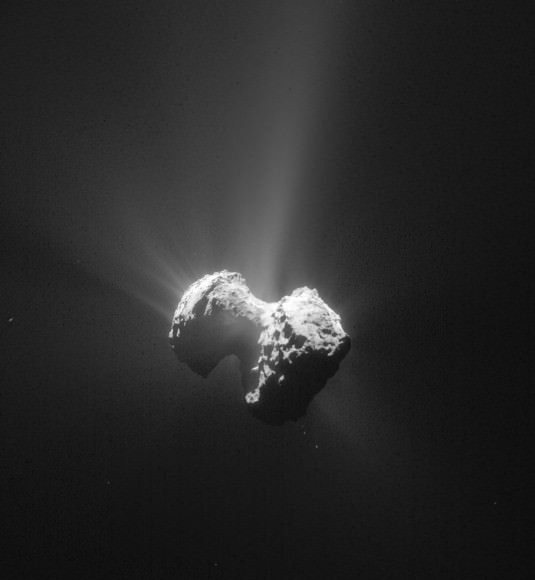

“With perihelion fast approaching, we are busy monitoring the comet’s activity from a safe distance and looking for any changes in the surface features, and we hope that Philae will be able to send us complementary reports from its location on the surface,” said Philae lander manager Stephan Ulamec.

Credits: ESA/Rosetta/MPS for OSIRIS Team MPS/UPD/LAM/IAA/SSO/INTA/UPM/DASP/IDA

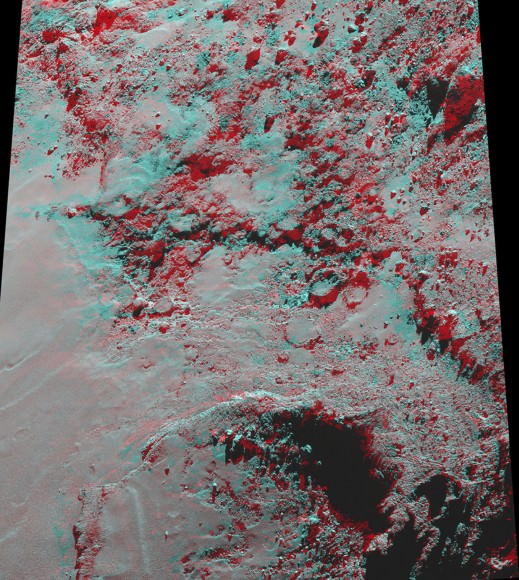

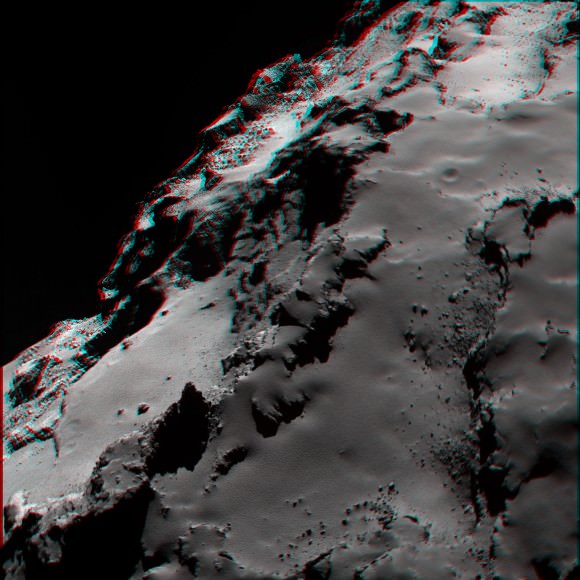

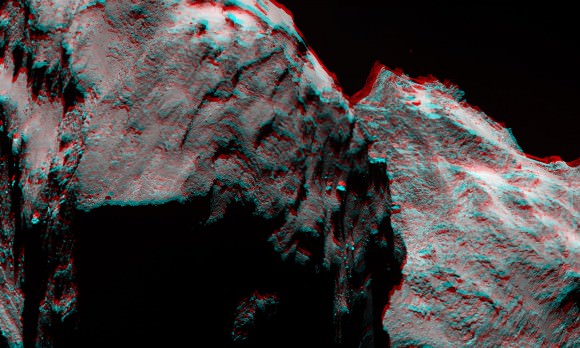

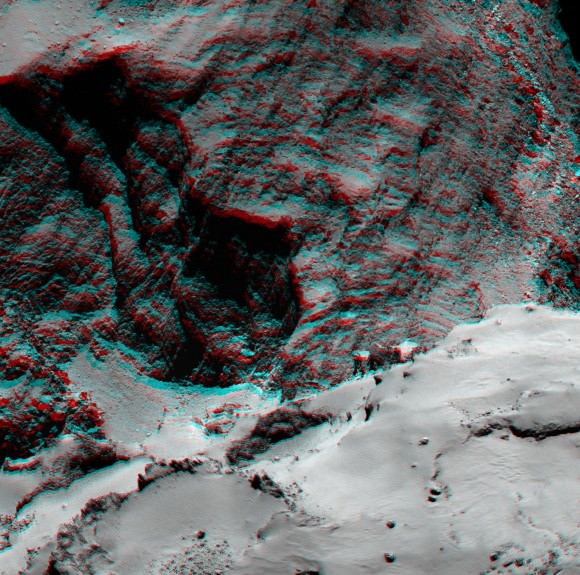

More about Philae’s findings can be found in the July 31 issue of Science. Before signing off, here are a few detailed, 3D images made with the high-resolution OSIRIS camera on Rosetta. Once you don a pair of red-blue glasses, click the photos for the high-res versions and get your mind blown.

Credits: ESA/Rosetta/MPS for OSIRIS Team MPS/UPD/LAM/IAA/SSO/INTA/UPM/DASP/IDA

Credits: ESA/Rosetta/MPS for OSIRIS Team MPS/UPD/LAM/IAA/SSO/INTA/UPM/DASP/IDA