[/caption]

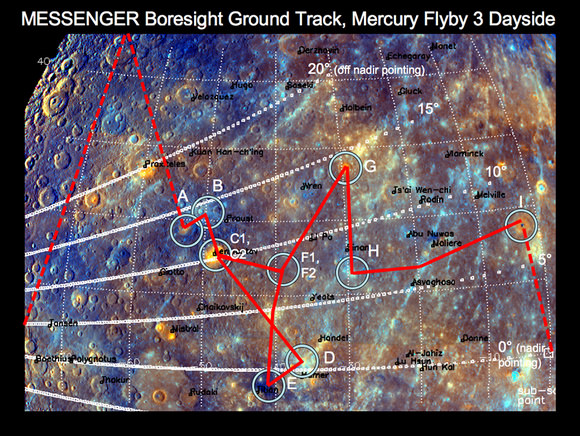

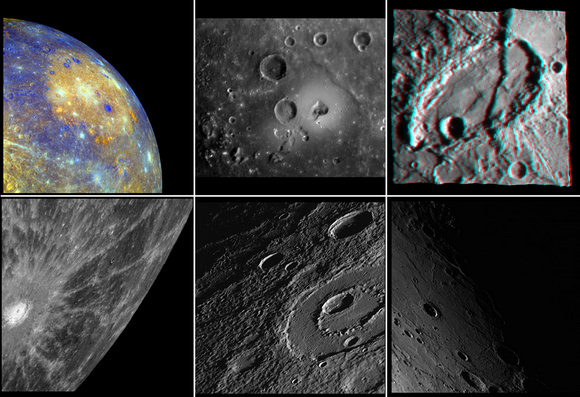

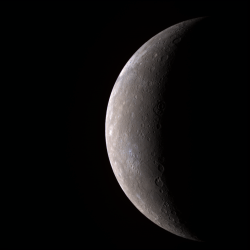

Younger volcanoes, stronger magnetic storms and a more intriguing exosphere: three new papers from data gathered during the MESSENGER spacecraft’s third flyby of Mercury in September of last year provide new insights into the planet closest to our Sun. The new findings make the science teams even more anxious for getting the spacecraft into orbit around Mercury. “Every time we’ve encountered Mercury, we’ve discovered new phenomena,” said principal investigator Sean Solomon. “We’re learning that Mercury is an extremely dynamic planet, and it has been so throughout its history. Once MESSENGER has been safely inserted into orbit about Mercury next March, we’ll be in for a terrific show.”

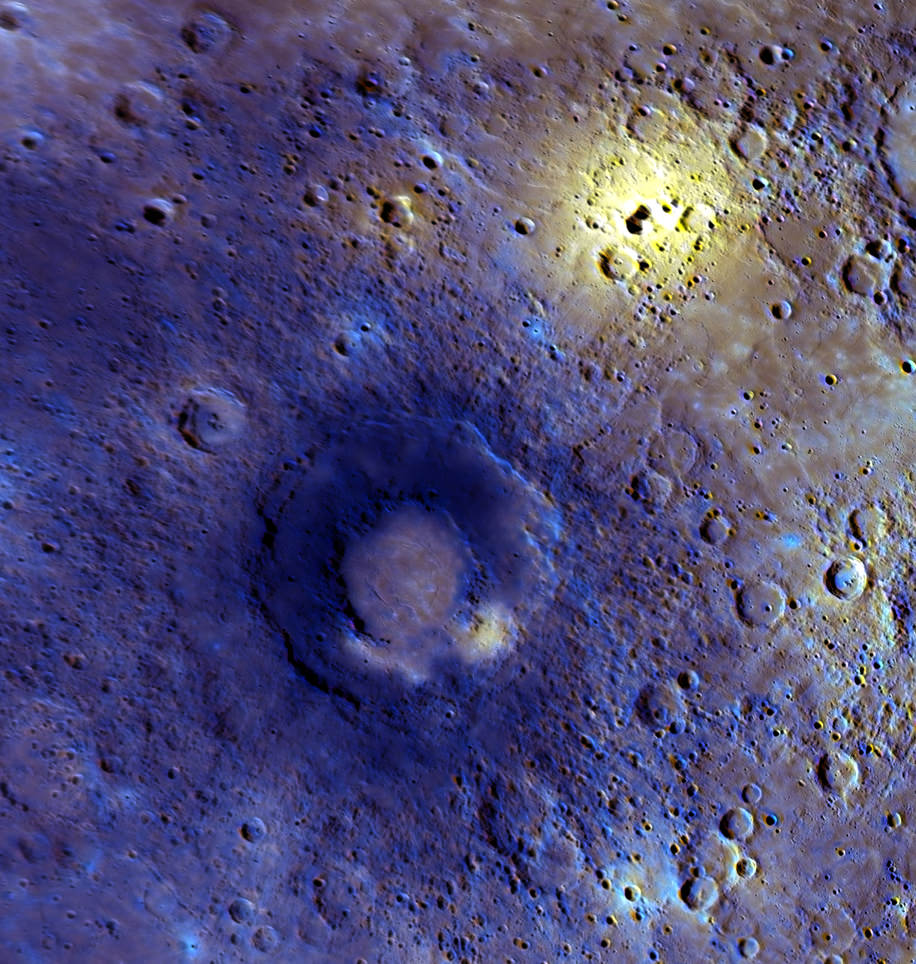

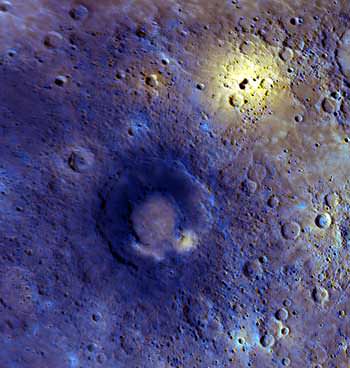

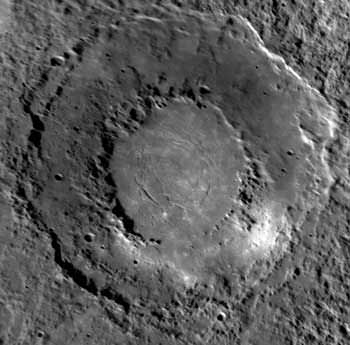

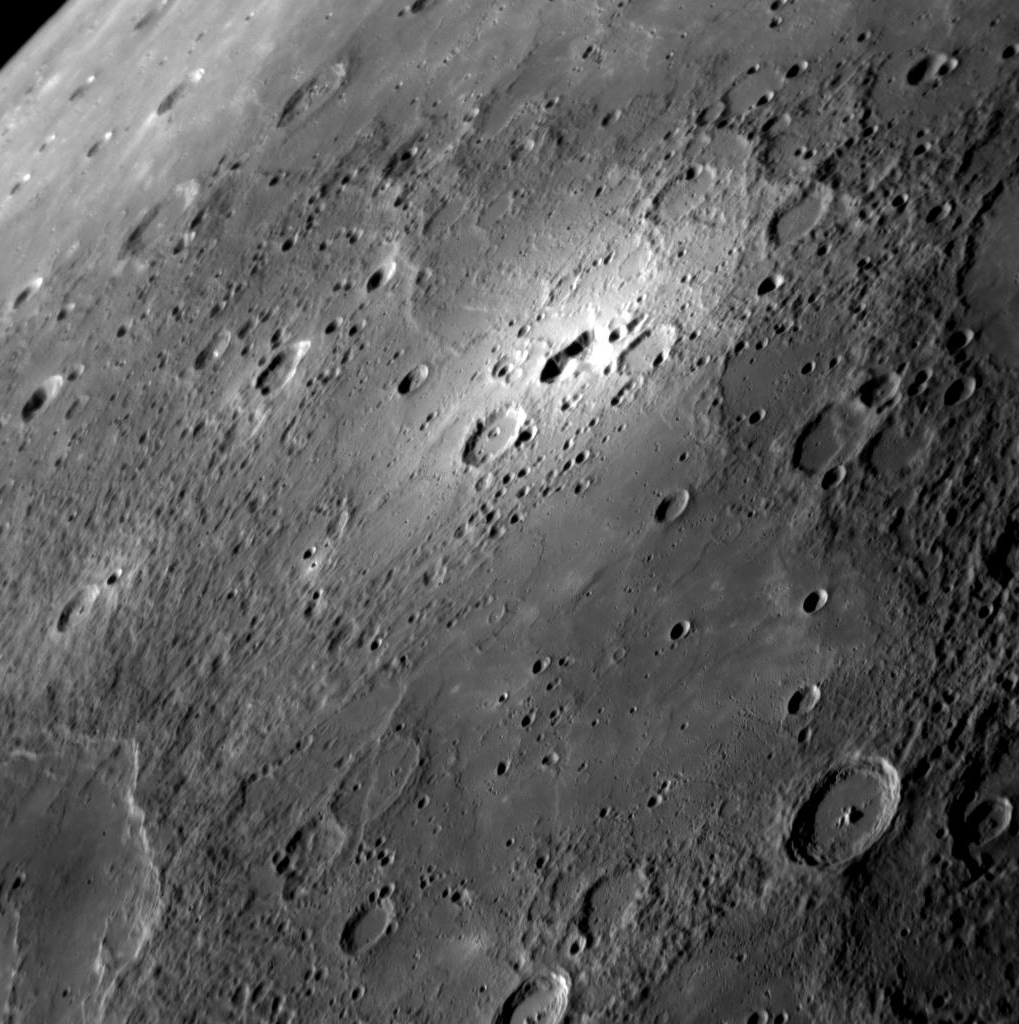

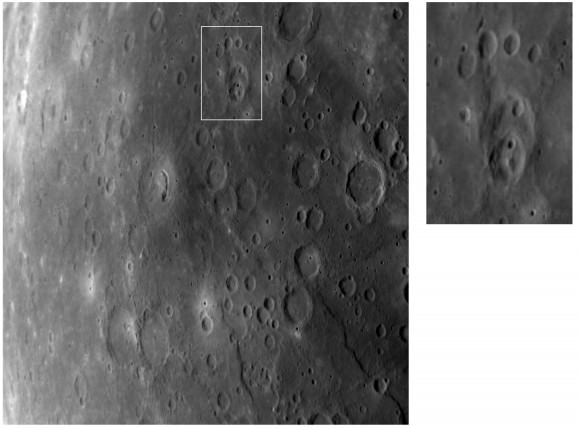

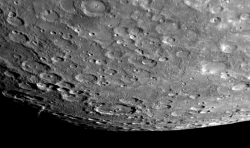

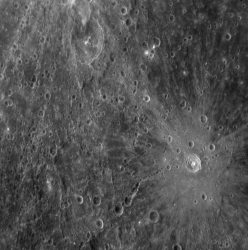

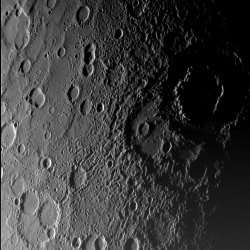

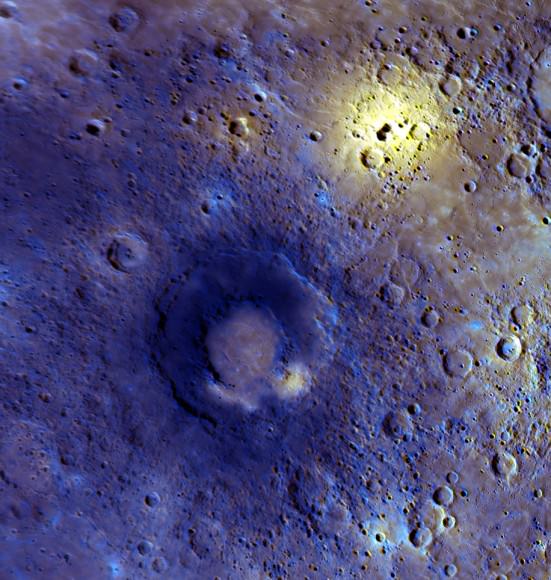

The closest look ever at some of Mercury’s plains suggests the planet’s volcanic activity lasted much longer than previously thought. From new images, researchers identified a 290-kilometer-diameter peak-ring impact basin, among the youngest to be observed on the planet. Named Rachmininoff, the region is characterized by exceptionally smooth, sparsely cratered plains, which formed later than the basin itself, likely from volcanic flow.

“We interpret these plains to be the youngest volcanic deposits yet found on Mercury,” said lead author Louise Prockter, from Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory, one of MESSENGER’s deputy project scientists. “Moreover, an irregular depression surrounded by a diffuse halo of bright material northeast of the basin marks a candidate explosive volcanic vent larger than any previously identified on Mercury.

These observations suggest that volcanism on the planet spanned a much greater duration than previously thought, perhaps extending well into the second half of solar system history.”

A depression northeast of the basin is surrounded by a halo of bright mineral deposits, which Prockter and her team propose to be the largest volcanic vent identified on Mercury so far. Both of these findings mean that volcanism continued well into the second half of our Solar System’s history.

During the third fly-by, the team was able to take measurements of Mercury’s magnetic field, and this happened to occur during a time when the planet was being hit by a strong solar wind. MESSENGER’s Magnetometer documented for the first time the substorm-like build-up, or “loading,” of magnetic energy in Mercury’s magnetic tail. The tail’s magnetic field increased and decreased by factors ranging from two to 3.5 during very brief periods of just two to three minutes.

“The extreme tail loading and unloading observed at Mercury implies that the relative intensity of substorms must be much larger than at Earth,” said lead author James A. Slavin, a space physicist at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center and a member of MESSENGER’s Science Team. “However, what is even more exciting is the correspondence between the duration of tail field enhancements and the Dungey cycle time, which describes plasma circulation through a magnetosphere.”

Substorms on Earth are powered by similar processes—except that the loading of our planet’s magnetosphere is ten times weaker and occurs over the course of a full hour. Therefore, the team said, Mercury’s substorms must release more energy than terrestrial ones.

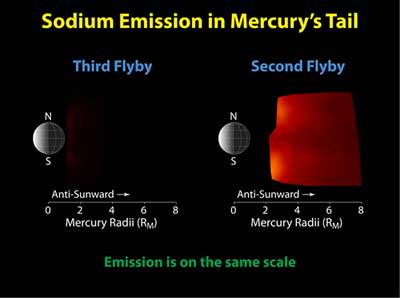

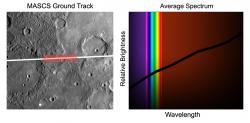

A third paper analyzed data from specialized instruments on-board the spacecraft to gain a clearer picture of Mercury’s neutral and ionic exospheres. Mercury’s exosphere is a tenuous atmosphere of atoms and ions derived from the planet’s surface and from the solar wind. Notable in the new observations were the differences in altitude of elements like magnesium, calcium, and sodium above the planet’s north and south poles. The team said this indicates that several processes are at work and that a given process may affect each element quite differently

“A striking feature in the near-planet tail ward region is the emission from neutral calcium atoms, which exhibits an equatorial peak in the dawn direction that has been consistent in both location and intensity through all three flybys,” said lead author Ron Vervack, also at the Applied Physics Laboratory. “The exosphere of Mercury is highly variable owing to Mercury’s eccentric orbit and the effects of a constantly changing space environment. That this observed calcium distribution has remained relatively unchanged is a complete surprise.”

The results are reported in three papers published online on July 15, 2010 in the Science Express section of the website of Science magazine.

Sources: EurekAlert, Science Express, MESSENGER website