On this date half a century ago the Soviet Luna 9 spacecraft made humanity’s first-ever soft landing on the surface of the Moon. Launched from Baikonur on Jan. 31, 1966, Luna 9 lander touched down within Oceanus Procellarum — somewhere in the neighborhood of 7.08°N, 64.37°E* — at 18:44:52 UTC on Feb. 3. The fourth successful mission in the USSR’s long-running Luna series, Luna 9 sent us our first views of the Moon’s surface from the surface and, perhaps even more importantly, confirmed that a landing by spacecraft was indeed possible.

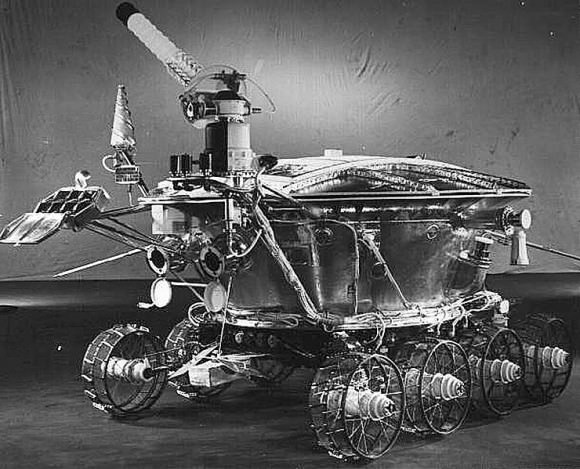

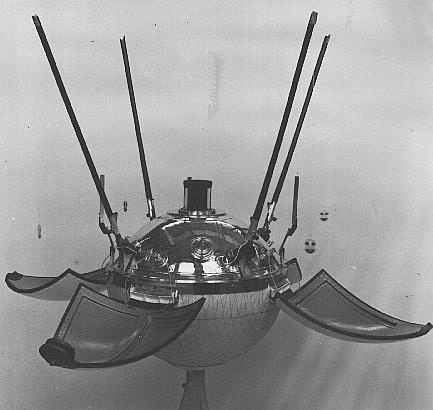

The entire Luna 9 lander was made up of two main parts: a 1,439-kg flight/descent stage which contained retro-rockets and orientation engines, navigation systems, and various fuel tanks, and a 99-kg (218-lb) pressurized “automatic lunar station” that contained all the science and imaging instruments along with batteries, heaters, and a radio transmitter.

When a probe on the descent stage detected contact with the lunar surface, the spherical station — encased in an inflated airbag — was jettisoned to soft-land a safe distance away — after a bit of bouncing, of course; the lander hit the Moon’s surface at about 22 km/hr (13 mph)!

Once the airbag cushions deflated Luna 9, like a shiny metal flower, opened its four “petals,” extended its radio antennas and began taking panoramic television camera images of its surroundings, at the time lit by a very low Sun on the lunar horizon. Received on Earth early on Feb. 4, 1966, they were the first pictures taken from the surface of the Moon and in fact the first images acquired from the surface of another world.

Read more: What Other Worlds Have We Landed On?

Other missions, both Soviet and American, had captured close-up images of the Moon in previous years but Luna 9 was the first to soft-land (i.e., not crash land) and operate from the surface. The spacecraft continued transmitting image data to Earth until its batteries ran out on the night of Feb. 6, 1966. A total of four panoramas were acquired by Luna 9 over the course of three days, as well as data on radiation levels on the Moon’s surface (not to mention the valuable knowledge that a spacecraft wouldn’t just completely sink into the lunar regolith!)

Four months later, on June 2, 1966, NASA’s Surveyor 1 would become the first U.S. spacecraft to soft-land on the Moon. Surveyor 1 would send back science data and 11,240 photos over the course of a month in operation but, in terms of the space “race,” Luna 9 will always be remembered as first place winner.

Want to see more pictures from Luna 9 and other Soviet Moon missions? Check out Don P. Mitchell’s dedicated page here, and learn more about the Luna program on Robert Christy’s Zarya site.

Sources: NASA/NSSDC, LPI, Robert Christy/Zarya

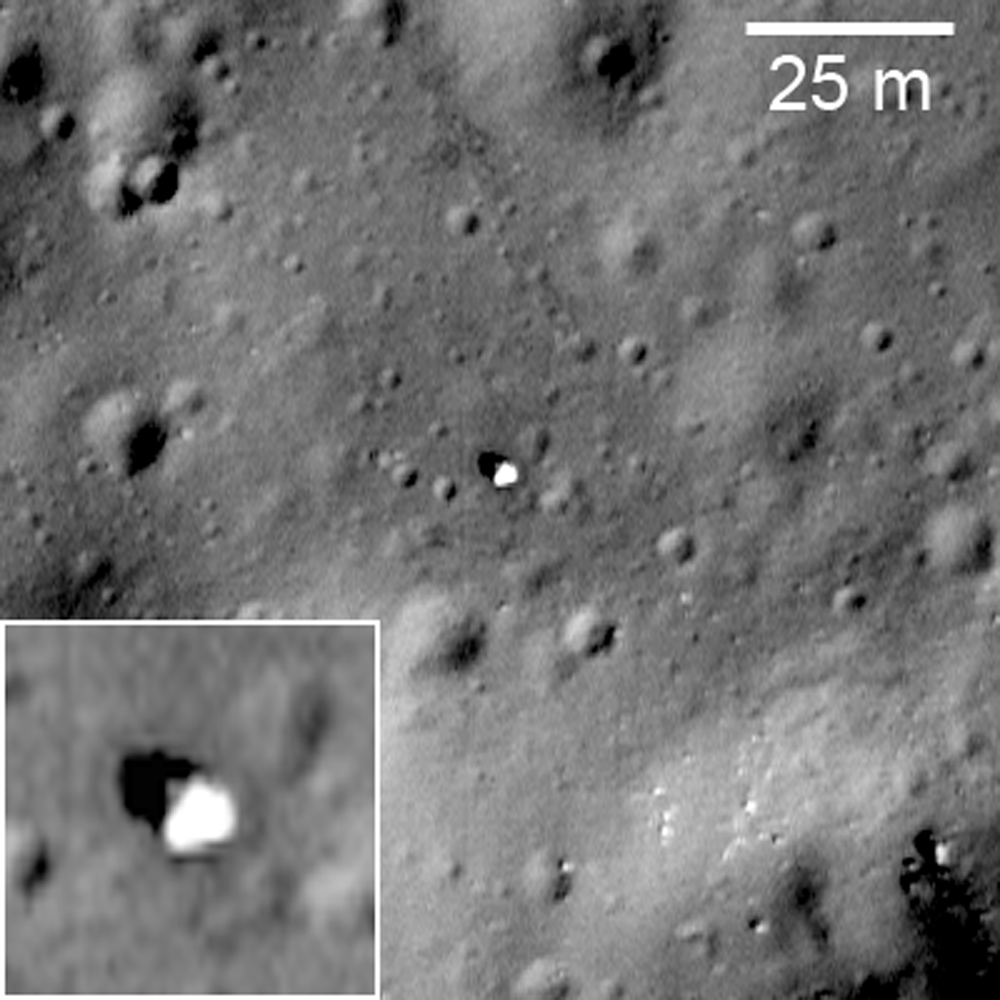

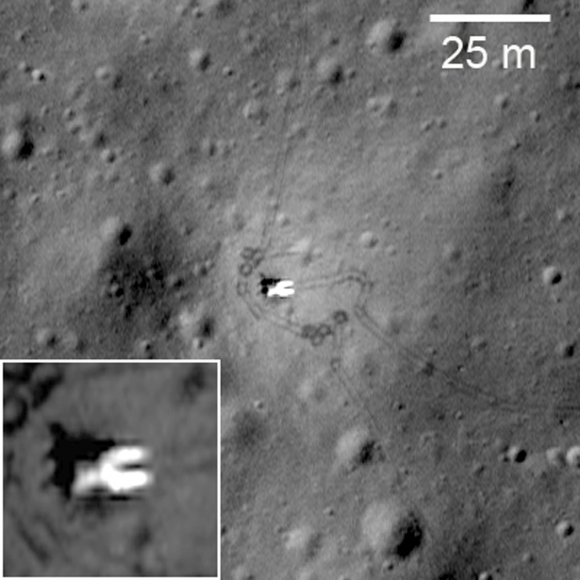

*Or is it 7.14°N/60.36°W? Even today it’s still not precisely known where Luna 9 landed, but researchers at Arizona State University are actively searching through Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter Camera pictures in an attempt to spot the “lost” spacecraft and/or evidence of its historic landing. Read more about that here.