Ever since Democritus – a Greek philosopher who lived between the 5th and 4th century’s BCE – argued that all of existence was made up of tiny indivisible atoms, scientists have been speculating as to the true nature of light. Whereas scientists ventured back and forth between the notion that light was a particle or a wave until the modern era, the 20th century led to breakthroughs that showed us that it behaves as both.

These included the discovery of the electron, the development of quantum theory, and Einstein’s Theory of Relativity. However, there remains many unanswered questions about light, many of which arise from its dual nature. For instance, how is it that light can be apparently without mass, but still behave as a particle? And how can it behave like a wave and pass through a vacuum, when all other waves require a medium to propagate?

Theory of Light to the 19th Century:

During the Scientific Revolution, scientists began moving away from Aristotelian scientific theories that had been seen as accepted canon for centuries. This included rejecting Aristotle’s theory of light, which viewed it as being a disturbance in the air (one of his four “elements” that composed matter), and embracing the more mechanistic view that light was composed of indivisible atoms.

In many ways, this theory had been previewed by atomists of Classical Antiquity – such as Democritus and Lucretius – both of whom viewed light as a unit of matter given off by the sun. By the 17th century, several scientists emerged who accepted this view, stating that light was made up of discrete particles (or “corpuscles”). This included Pierre Gassendi, a contemporary of René Descartes, Thomas Hobbes, Robert Boyle, and most famously, Sir Isaac Newton.

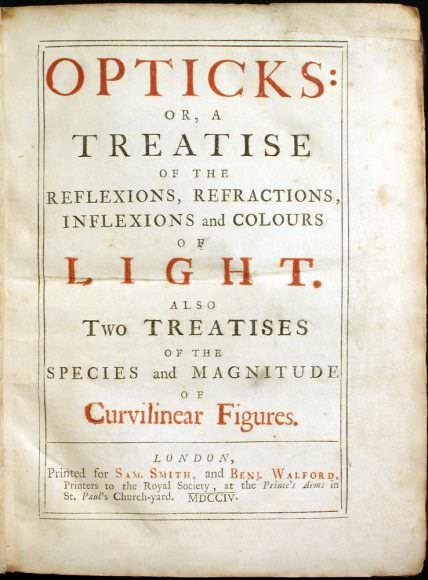

Newton’s corpuscular theory was an elaboration of his view of reality as an interaction of material points through forces. This theory would remain the accepted scientific view for more than 100 years, the principles of which were explained in his 1704 treatise “Opticks, or, a Treatise of the Reflections, Refractions, Inflections, and Colours of Light“. According to Newton, the principles of light could be summed as follows:

- Every source of light emits large numbers of tiny particles known as corpuscles in a medium surrounding the source.

- These corpuscles are perfectly elastic, rigid, and weightless.

This represented a challenge to “wave theory”, which had been advocated by 17th century Dutch astronomer Christiaan Huygens. . These theories were first communicated in 1678 to the Paris Academy of Sciences and were published in 1690 in his “Traité de la lumière“ (“Treatise on Light“). In it, he argued a revised version of Descartes views, in which the speed of light is infinite and propagated by means of spherical waves emitted along the wave front.

Double-Slit Experiment:

By the early 19th century, scientists began to break with corpuscular theory. This was due in part to the fact that corpuscular theory failed to adequately explain the diffraction, interference and polarization of light, but was also because of various experiments that seemed to confirm the still-competing view that light behaved as a wave.

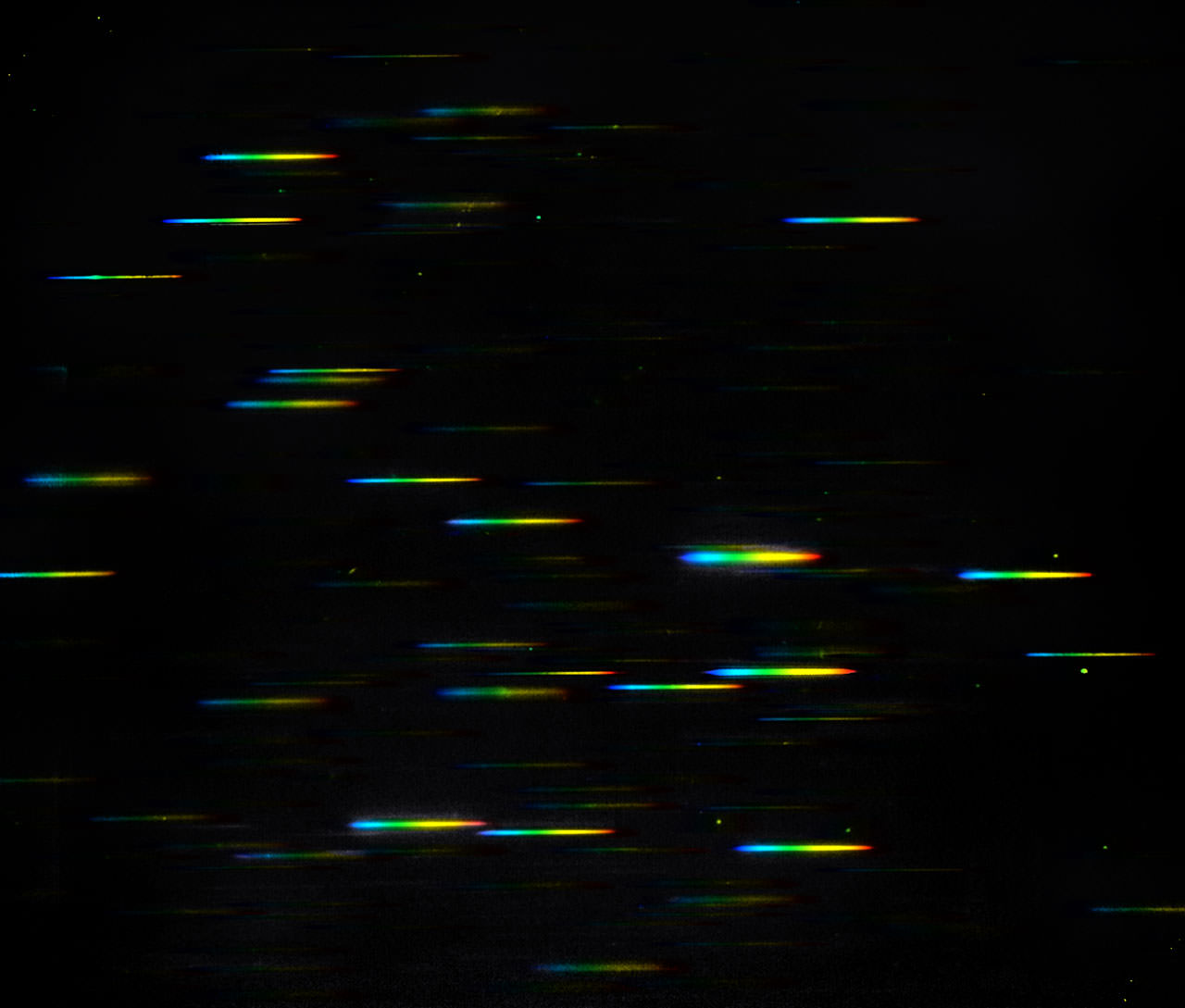

The most famous of these was arguably the Double-Slit Experiment, which was originally conducted by English polymath Thomas Young in 1801 (though Sir Isaac Newton is believed to have conducted something similar in his own time). In Young’s version of the experiment, he used a slip of paper with slits cut into it, and then pointed a light source at them to measure how light passed through it.

According to classical (i.e. Newtonian) particle theory, the results of the experiment should have corresponded to the slits, the impacts on the screen appearing in two vertical lines. Instead, the results showed that the coherent beams of light were interfering, creating a pattern of bright and dark bands on the screen. This contradicted classical particle theory, in which particles do not interfere with each other, but merely collide.

The only possible explanation for this pattern of interference was that the light beams were in fact behaving as waves. Thus, this experiment dispelled the notion that light consisted of corpuscles and played a vital part in the acceptance of the wave theory of light. However subsequent research, involving the discovery of the electron and electromagnetic radiation, would lead to scientists considering yet again that light behaved as a particle too, thus giving rise to wave-particle duality theory.

Electromagnetism and Special Relativity:

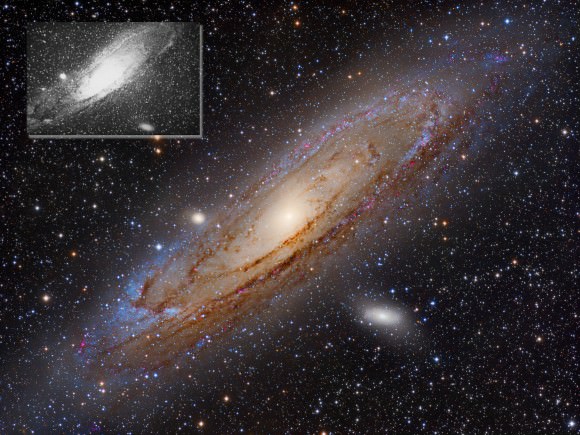

Prior to the 19th and 20th centuries, the speed of light had already been determined. The first recorded measurements were performed by Danish astronomer Ole Rømer, who demonstrated in 1676 using light measurements from Jupiter’s moon Io to show that light travels at a finite speed (rather than instantaneously).

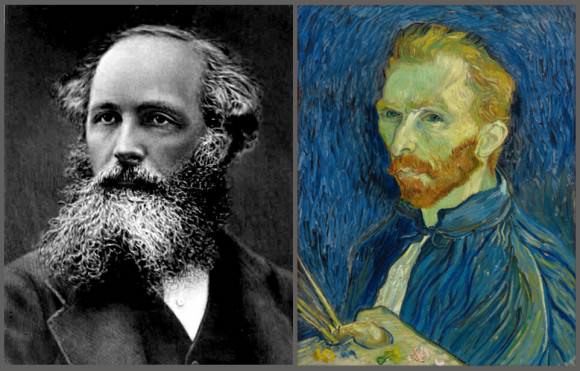

By the late 19th century, James Clerk Maxwell proposed that light was an electromagnetic wave, and devised several equations (known as Maxwell’s equations) to describe how electric and magnetic fields are generated and altered by each other and by charges and currents. By conducting measurements of different types of radiation (magnetic fields, ultraviolet and infrared radiation), he was able to calculate the speed of light in a vacuum (represented as c).

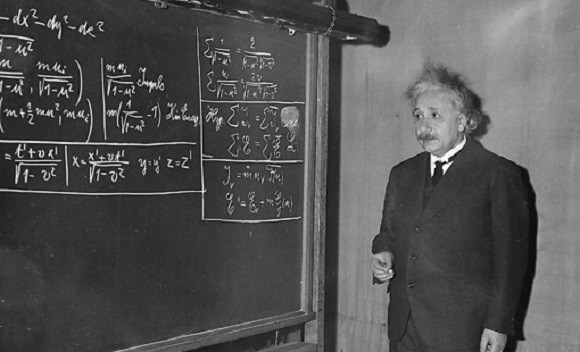

In 1905, Albert Einstein published “On the Electrodynamics of Moving Bodies”, in which he advanced one of his most famous theories and overturned centuries of accepted notions and orthodoxies. In his paper, he postulated that the speed of light was the same in all inertial reference frames, regardless of the motion of the light source or the position of the observer.

Exploring the consequences of this theory is what led him to propose his theory of Special Relativity, which reconciled Maxwell’s equations for electricity and magnetism with the laws of mechanics, simplified the mathematical calculations, and accorded with the directly observed speed of light and accounted for the observed aberrations. It also demonstrated that the speed of light had relevance outside the context of light and electromagnetism.

For one, it introduced the idea that major changes occur when things move close the speed of light, including the time-space frame of a moving body appearing to slow down and contract in the direction of motion when measured in the frame of the observer. After centuries of increasingly precise measurements, the speed of light was determined to be 299,792,458 m/s in 1975.

Einstein and the Photon:

In 1905, Einstein also helped to resolve a great deal of confusion surrounding the behavior of electromagnetic radiation when he proposed that electrons are emitted from atoms when they absorb energy from light. Known as the photoelectric effect, Einstein based his idea on Planck’s earlier work with “black bodies” – materials that absorb electromagnetic energy instead of reflecting it (i.e. white bodies).

At the time, Einstein’s photoelectric effect was attempt to explain the “black body problem”, in which a black body emits electromagnetic radiation due to the object’s heat. This was a persistent problem in the world of physics, arising from the discovery of the electron, which had only happened eight years previous (thanks to British physicists led by J.J. Thompson and experiments using cathode ray tubes).

At the time, scientists still believed that electromagnetic energy behaved as a wave, and were therefore hoping to be able to explain it in terms of classical physics. Einstein’s explanation represented a break with this, asserting that electromagnetic radiation behaved in ways that were consistent with a particle – a quantized form of light which he named “photons”. For this discovery, Einstein was awarded the Nobel Prize in 1921.

Wave-Particle Duality:

Subsequent theories on the behavior of light would further refine this idea, which included French physicist Louis-Victor de Broglie calculating the wavelength at which light functioned. This was followed by Heisenberg’s “uncertainty principle” (which stated that measuring the position of a photon accurately would disturb measurements of it momentum and vice versa), and Schrödinger’s paradox that claimed that all particles have a “wave function”.

In accordance with quantum mechanical explanation, Schrodinger proposed that all the information about a particle (in this case, a photon) is encoded in its wave function, a complex-valued function roughly analogous to the amplitude of a wave at each point in space. At some location, the measurement of the wave function will randomly “collapse”, or rather “decohere”, to a sharply peaked function. This was illustrated in Schrödinger famous paradox involving a closed box, a cat, and a vial of poison (known as the “Schrödinger Cat” paradox).

According to his theory, wave function also evolves according to a differential equation (aka. the Schrödinger equation). For particles with mass, this equation has solutions; but for particles with no mass, no solution existed. Further experiments involving the Double-Slit Experiment confirmed the dual nature of photons. where measuring devices were incorporated to observe the photons as they passed through the slits.

When this was done, the photons appeared in the form of particles and their impacts on the screen corresponded to the slits – tiny particle-sized spots distributed in straight vertical lines. By placing an observation device in place, the wave function of the photons collapsed and the light behaved as classical particles once more. As predicted by Schrödinger, this could only be resolved by claiming that light has a wave function, and that observing it causes the range of behavioral possibilities to collapse to the point where its behavior becomes predictable.

The development of Quantum Field Theory (QFT) was devised in the following decades to resolve much of the ambiguity around wave-particle duality. And in time, this theory was shown to apply to other particles and fundamental forces of interaction (such as weak and strong nuclear forces). Today, photons are part of the Standard Model of particle physics, where they are classified as boson – a class of subatomic particles that are force carriers and have no mass.

So how does light travel? Basically, traveling at incredible speeds (299 792 458 m/s) and at different wavelengths, depending on its energy. It also behaves as both a wave and a particle, able to propagate through mediums (like air and water) as well as space. It has no mass, but can still be absorbed, reflected, or refracted if it comes in contact with a medium. And in the end, the only thing that can truly divert it, or arrest it, is gravity (i.e. a black hole).

What we have learned about light and electromagnetism has been intrinsic to the revolution which took place in physics in the early 20th century, a revolution that we have been grappling with ever since. Thanks to the efforts of scientists like Maxwell, Planck, Einstein, Heisenberg and Schrodinger, we have learned much, but still have much to learn.

For instance, its interaction with gravity (along with weak and strong nuclear forces) remains a mystery. Unlocking this, and thus discovering a Theory of Everything (ToE) is something astronomers and physicists look forward to. Someday, we just might have it all figured out!

We have written many articles about light here at Universe Today. For example, here’s How Fast is the Speed of Light?, How Far is a Light Year?, What is Einstein’s Theory of Relativity?

If you’d like more info on light, check out these articles from The Physics Hypertextbook and NASA’s Mission Science page.

We’ve also recorded an entire episode of Astronomy Cast all about Interstellar Travel. Listen here, Episode 145: Interstellar Travel.