[/caption]

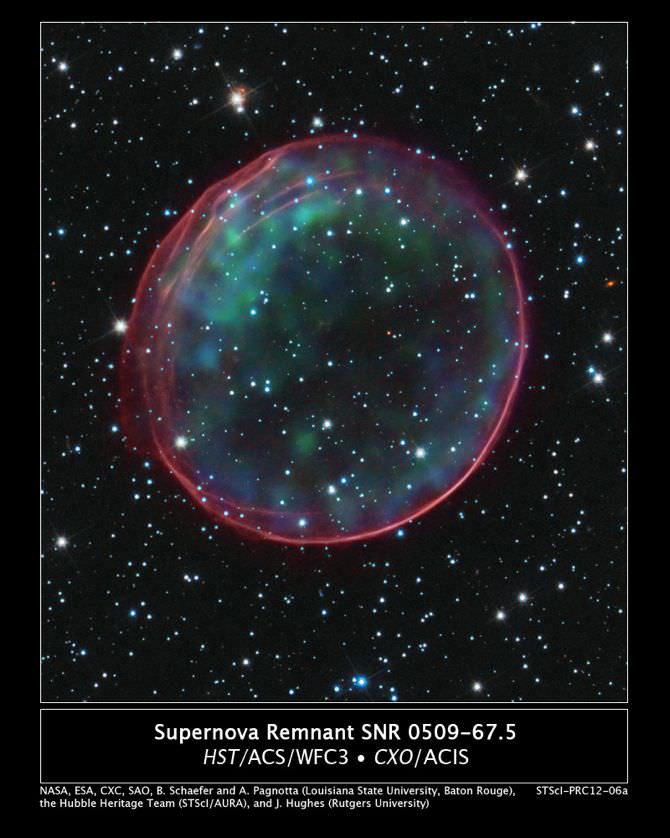

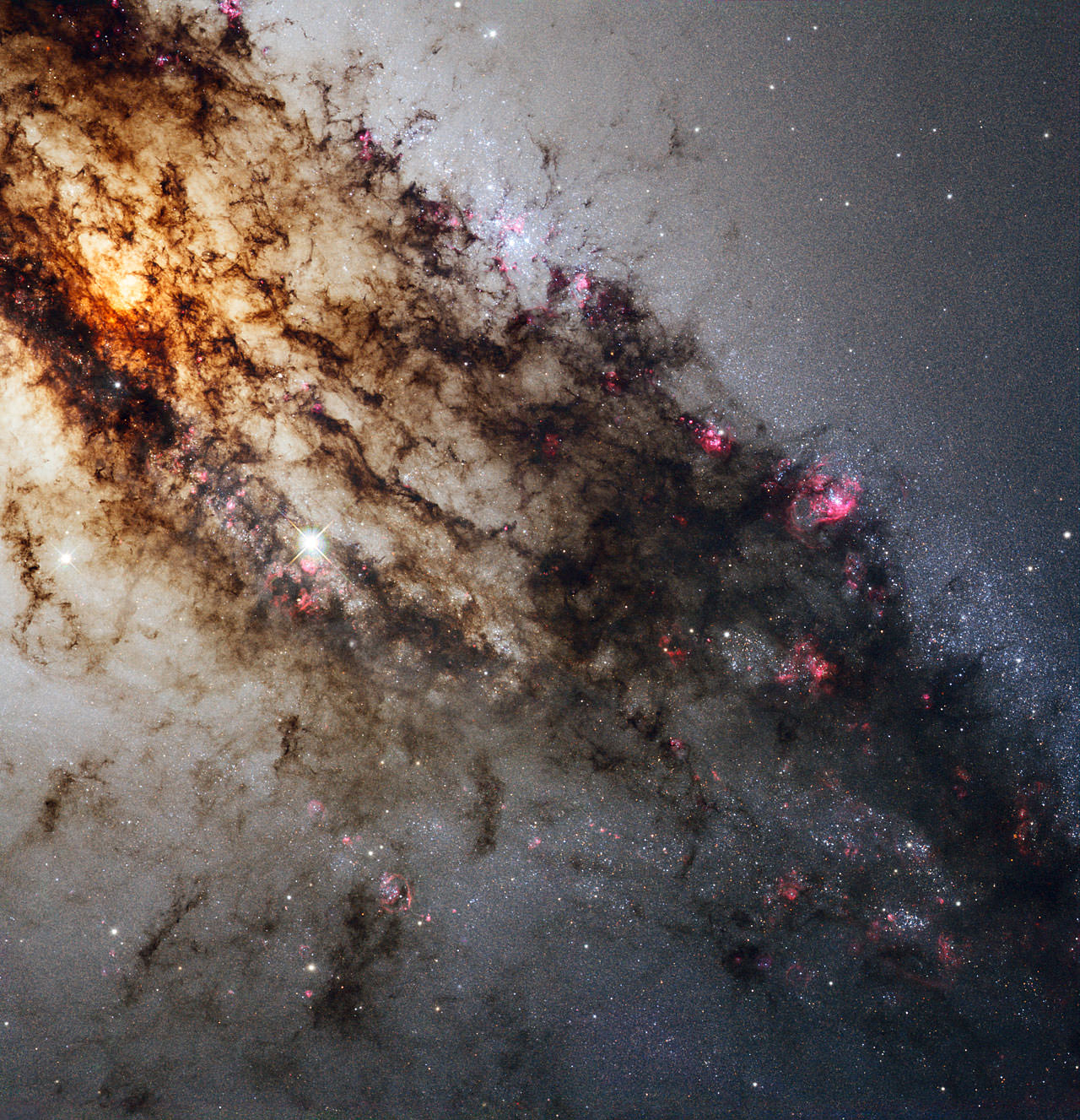

What happened 400 years ago to create this stunningly beautiful supernova remnant – and were there two culprits or just one? This Hubble Space Telescope view of a Type Ia-created remnant has helped astronomers solve a longstanding mystery on the type of stars that cause some supernovae, known as a progenitor.

“Up until this point we haven’t really known where this type of supernova came from, despite studying them for decades,” said Ashley Pagnotta of Louisiana State University, speaking at a press briefing at the American Astronomical Society meeting on Wednesday. “But we now can say we have the first definitive identification of a Type 1a progenitor, and we know this one must have had a double degenerate progenitor – it is the only option.”

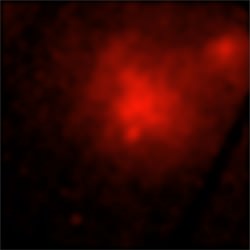

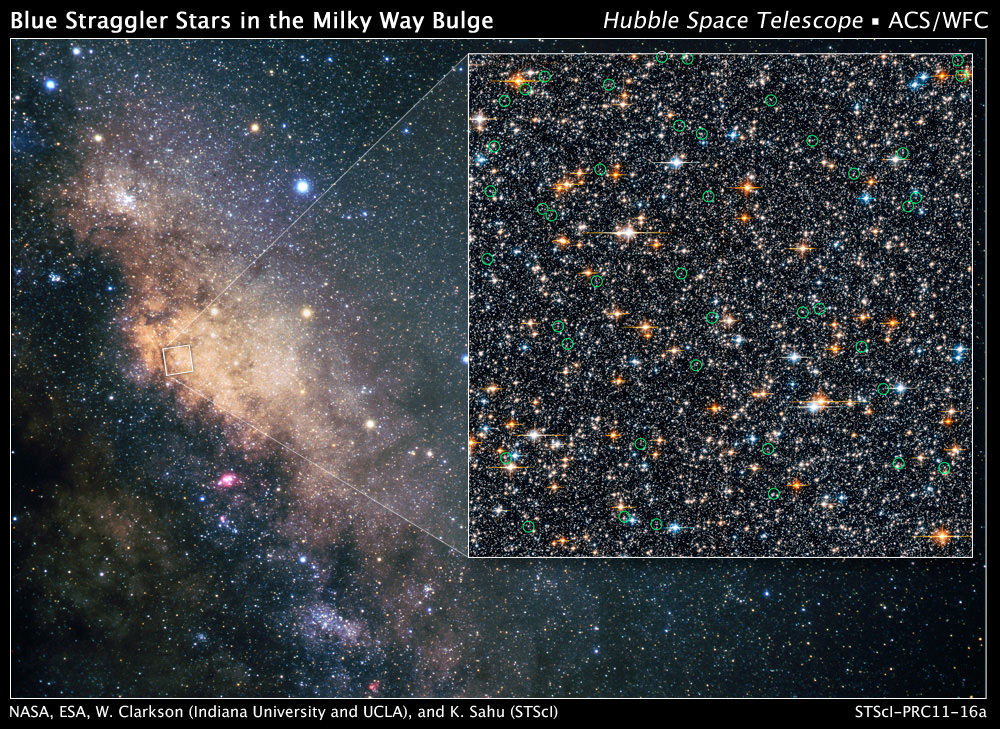

This supernova remnant that has a telephone number-like name of SNR 0509-67.5, lies 170,000 light-years away in the Large Magellanic Cloud galaxy.

Astronomers have long suspected that two stars were responsible for the explosion – as is the case with most type 1a supernovae — but weren’t sure what triggered the explosion. One explanation could be that it was caused by mass transfer from a companion star where a nearby star spills material onto a white dwarf companion, setting off a chain reaction that causes one of the most powerful explosions in the universe. This is known as the ‘single-degenerate’ path – which seems to be the most plausible, common and most preferred explanation for many Type 1a supernovae.

The other option is the collision of two white dwarfs, which is known as ‘double-degenerate, which seems to be the less common and not as widely accepted explanation for supernovae. To many astrophysicists, the merger scenario seemed to be less likely because too few double-white-dwarf systems appear to exist; indeed, there appear to be just handful that have been discovered so far.

The problem with SNR 0509-67.5 was that astronomers could not find any remnant of the companion star. That’s why the double degenerate scenario was considered, as in that case, there won’t be anything left as both white dwarfs are consumed in the explosion. In the case of a single progenitor, the non-white dwarf star will still be near the explosion site and will still look very much as it did before the explosion.

Therefore, a possible way to distinguish between the various progenitor models has been to look deep in the center of an old supernova remnant to search for the ex-companion star.

“We know Hubble has the sensitivity necessary to detect the faintest white dwarf remnants that could have caused such explosions,” said lead investigator Bradley Schaefer from LSU. “The logic here is the same as the famous quote from Sherlock Holmes: ‘when you have eliminated the impossible, whatever remains, however improbable, must be the truth.'”

In 2010, Schaefer and Pagnotta were preparing a proposal to look for any faint ex-companion stars in the center of four supernova remnants in the Large Magellanic Cloud when they saw an Astronomy Picture of the Day photo showing an image the Hubble Space Telescope had already had taken of one of their target remnants, SNR 0509-67.5.

(Note: the January 12, 2012 APOD image is of SNR 0509-67.5!)

Because the remnant appears as a nice symmetric shell or bubble, the geometric center can be determined accurately. In analyzing in more detail the central region, they found it to be completely empty of stars down to the limit of the faintest objects Hubble can detect in the photos. The young age also means that any surviving stars have not moved far from the site of the explosion. They were able to cross off the list all the possible single degenerate scenarios, and were left with the double degenerate model in which two white dwarfs collide.

“Since we can exclude all the possible single degenerates, we know it must be a double degenerate,” Pagnotta said. “The cause of SNR 0509-67.5 can be explained best by two tightly orbiting white dwarf stars spiraling closer and closer until they collided and exploded.”

Pagnotta also noted that this supernova is actually not a normal Type 1a supernova, but a subclass called 1991t, which is an extra bright supernova.

A paper in 2010 by Marat Gilfanov of the Max Planck Institute for Astrophysics indicated that perhaps many Type 1a supernova were caused by two white dwarf stars colliding, which was a surprise to many astronomers. Additionally, a review of the recent supernova SN 2011fe, which exploded in August of 2011, explores the possibility of the double degenerate progenitor. An open question remains whether these white dwarf mergers are the primary catalyst for Type Ia supernovae in spiral galaxies. Further studies are required to know if supernovae in spiral galaxies are caused by mergers or a mixture of the two processes.

Schaefer and Pagnotta plan to look at other supernova remnants in the Large Magellenic Cloud to further test their observations.

Pagnotta confirmed that anyone with an internet connection could have made this discovery, as all the Hubble images used were available publicly, and the use of the Hubble data was sparked by APOD.

Sources: Science Paper by Bradley E. Schaefer and Ashley Pagnotta (PDF document), HubbleSite, AAS press briefing