So, heard the one about this weekend’s impending ‘Super-Harvest-Blood-Moon eclipse?’ Yeah, us too. Have no fear; fortunately for humanity, the total lunar eclipse transpiring on Sunday night/Monday morning is a harbinger of nothing more than a fine celestial spectacle, clear skies willing.

This final eclipse of the ongoing lunar tetrad has some noteworthy events worth exploring in terms of science and lore.

The Supermoon Total Lunar Eclipse of September 27-28 2015 from Michael Zeiler on Vimeo.

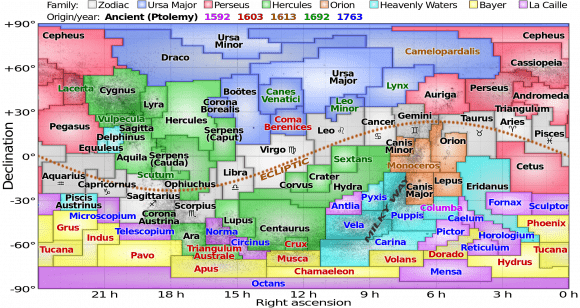

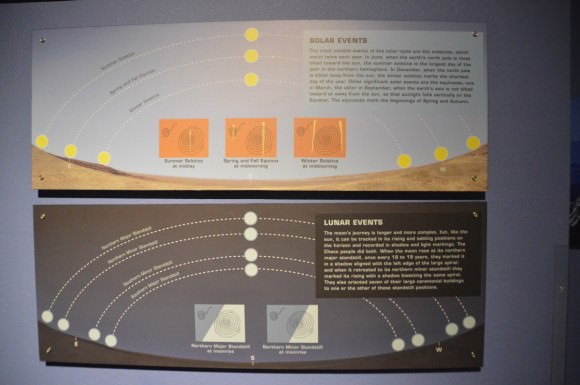

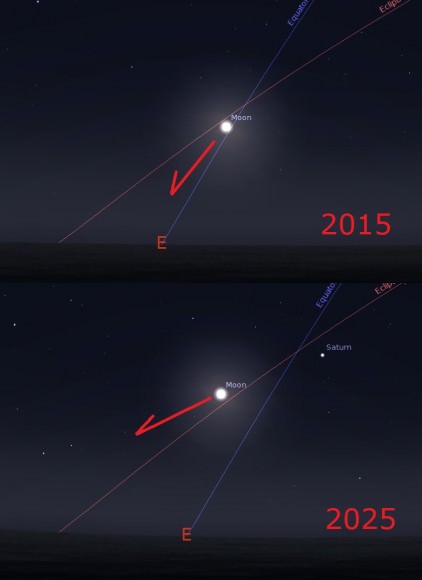

The Specifics: First, you almost couldn’t ask for better timing. This weekend’s total lunar eclipse occurs during prime time Sunday night for North and South America, and early Monday morning for Europe, Africa and most of the Middle East. This means the Atlantic Region and surrounding areas will see totality in its entirety. This eclipse occurs very near the northward equinoctial point occupied by the Sun during the Northern Hemisphere Spring equinox in March. The date says it all: this eclipse coincides with the Harvest Moon for 2015, falling just under five days after the September equinox.

For saros buffs, Sunday’s eclipse is part of lunar saros series 137, member 28 of 81. This saros started back in 1564 and produced its first total lunar eclipse just two cycles ago on September 6th 1979. Saros 137 runs all the way out to its final eclipse on April 20th, 2953 AD.

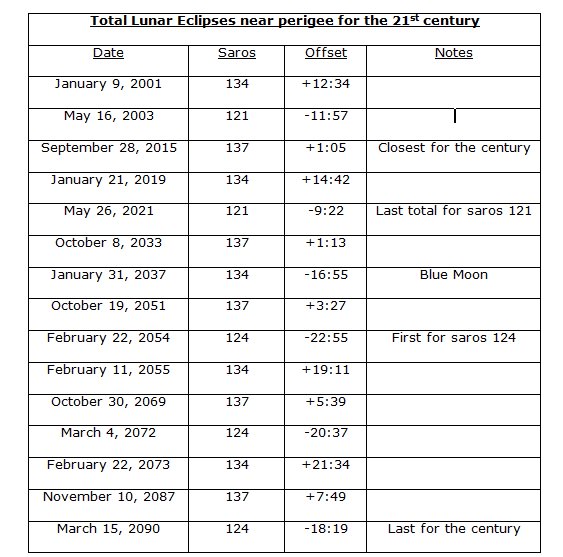

And yes, this upcoming total lunar eclipse occurs very near the closest lunar perigee for 2015. How rare are ‘Supermoon’ lunar eclipses? Well, we took a look at the phenomenon, and found 15 total lunar eclipses occurring near lunar perigee for the current century:

You’ll note that four saroses (the plural of saros) are producing perigee or ‘Proxigean’ total lunar eclipses during this century, including saros 137.

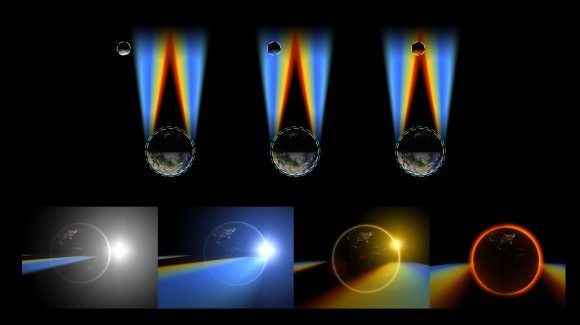

Does the perigee Moon effect the length of totality? It’s an interesting question. Several factors come into play that are worth considering for Sunday night’s eclipse. First, the Moon moves a bit faster near perigee as per Kepler’s second law of motion. Second, the Moon is a shade larger in apparent size, 34’ versus 29’ near apogee. Lastly, the conic section of the Earth’s shadow or umbra is a bit larger closer in; you can fit three Moons side-by-side across the umbra around 400,000 kilometers out from the Earth. Sunday night’s perigee occurs 65 minutes after Full Moon at 2:52 UT/10:52 PM EDT. Perigee Sunday night is 356,876 kilometers distant, the closest for 2015 by just 115 kilometers, and just under 500 kilometers short of the closest perigee that can occur. This is, however, the closest perigee time-wise to lunar totality for the 21st century; you have to go all the way back to 1897 to find one closer, at just four minutes apart.

Now, THAT was and eclipse!

This all culminates in a period for totality on Sunday night of just under 72 minutes in duration, 35 minutes shy of the maximum possible for a central total lunar eclipse. An eclipse won’t top this weekend’s in terms of duration until January 31st 2018.

Here are the key times to watch for on Sunday night:

Penumbral phase begins: 00:12 UT/8:12 PM EDT (on the 27th)

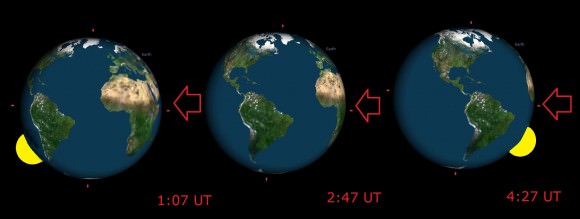

Partial phase begins: 1:07 UT/9:07 PM EDT

Totality begins: 2:11 UT/10:11 PM EDT

Totality ends: 3:23 UT/11:23 PM EDT

Partial phase ends: 4:27 UT/00:27 AM EDT

Penumbral phase ends: 5:22 UT/1:22 AM EDT

Note that one 18 year 11 day and 8 hour saros period later, saros 137 will again produce a perigee eclipse nearly as close as this weekend’s on October 8th, 2033.

The classic hallmark of any total lunar eclipse is the reddening of the Moon. You’re seeing the combination of all the world’s sunsets, refracted into the inky umbra of the Earth and cast upon the surface of the Moon. To date, no human has stood upon the surface of the Moon and gazed upon the spectacle of a solar eclipse caused by the Earth.

Not all eclipses are created equal when it comes to hue and color. The amount of dust and aerosols suspended in the atmosphere can conspire to produce anything from a bright, yellowish-orange tint, to a brick dark eclipse where the Moon almost disappears from view entirely. The recent rapid fire tetrad of four eclipses in 18 months has provided a good study in eclipse color intensity. The deeper the Moon dips into the Earth’s shadow, the darker it will appear… last April’s lunar eclipse was just barely inside the umbra, making many observers question if the eclipse was in fact total at all.

We the describe color of the eclipsed Moon in terms of its number on the Danjon scale, and recent volcanic activity worldwide suggests that we may be in for a darker than normal eclipse… but we could always be in for a surprise!

Old time mariners including James Cook and Christopher Columbus used positional measurements of the eclipsed Moon at sea versus predictions published in almanac tables for land-based observatories to get a one-time fix on their longitude, a fun experiment to try to replicate today. Kris Columbus also wasn’t above using beforehand knowledge of an impending lunar eclipse to help get his crew out of a tight jam.

And speaking of the next perigee Moon total lunar eclipse for saros 137 on October 8th, 2033… if you catch that one, this weekend’s, and saw the September 16th, 1997 lunar eclipse which spanned the Indian Ocean region, you’ll have completed an exeligmos, or a triple saros of eclipses in the same series 54 years and 33 days in length, an exclusive club among eclipse watchers and a great word to land on a triple letter word score in Scrabble…

Exeligmos is also the title of one of our original scifi tales involving eclipses, along with Shadowfall.

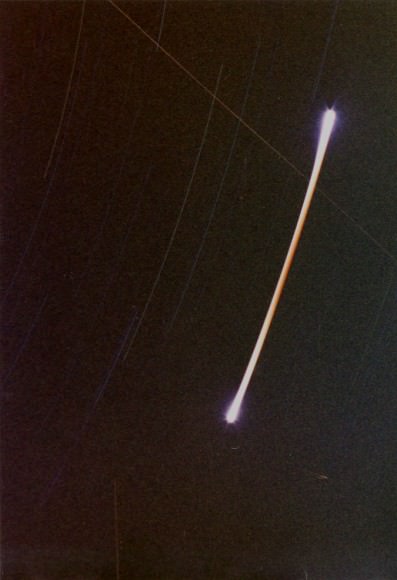

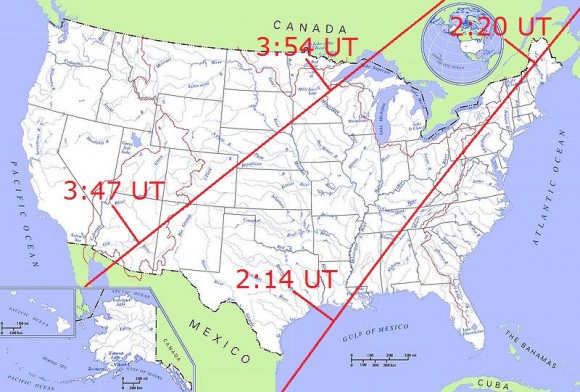

Here’s another neat challenge: the International Space Station makes two shadow passes during the lunar eclipse over the contiguous United States. The first one occurs during totality, and spans from eastern Louisiana to central Maine from 2:14 to 2:20 UT; the second pass occurs during the final partial phases of the eclipse spanning from southern Arizona to Lake Superior from 3:47 to 3:54 UT. These are un-illuminated shadow passes of the ISS. Observers have captured transits of the ISS during a partial solar eclipse, but to our knowledge, no one has ever caught a transit of the ISS during a total lunar eclipse; ISS astros should also briefly be able to spy the eclipsed Moon from their orbital vantage point. CALSky will have refined passage times about 48 hours prior to Sunday.

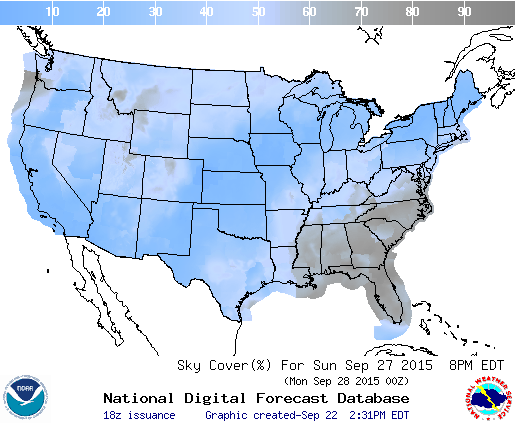

Clouded out? Live on the wrong side of the planet? The good folks at the Virtual Telescope Project have got you covered, with a live webcast of the total lunar eclipse starting at 1:00 UT/9:00 PM EDT.

And as the eclipse draws to an end, the question of the hour always is: when’s the next one? Well, the next lunar eclipse is a dim penumbral on March 23rd, 2016, which follows a total solar eclipse for southeastern Asia on March 9th, 2016… but the next total lunar won’t occur until January 31st, 2018, which also happens to be the second Full Moon of the month… a ‘Blue Blood Moon Eclipse?’

Sorry, we had to go there. Hey, we could make the case for Sunday’s eclipse also occurring on World Rabies Day, but perhaps a ‘Rabies Eclipse’ just doesn’t have the SEO traction. Don’t fear the Blood Moon, but do get out and watch the final lunar eclipse of 2015 on Sunday night!