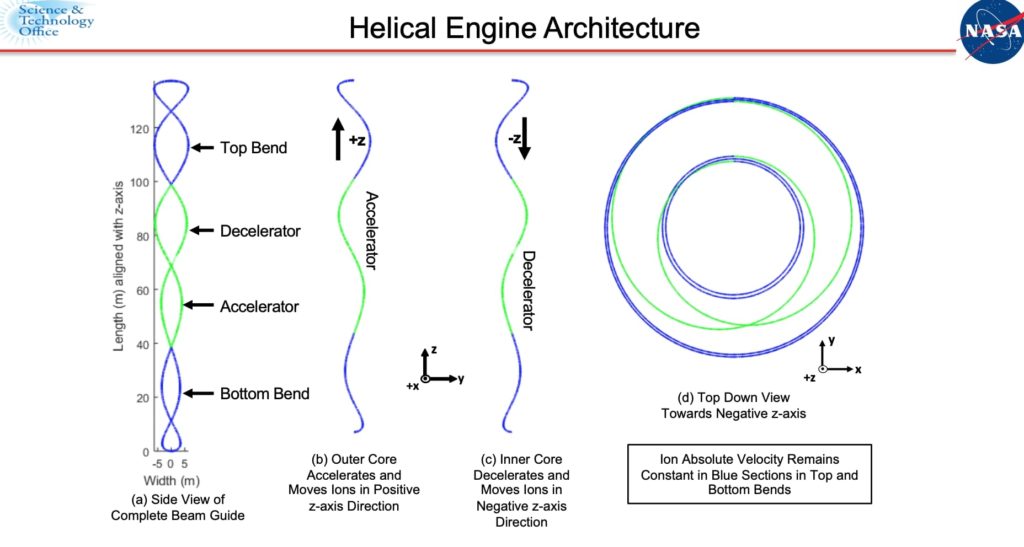

When a NASA engineer announces a new and revolutionary engine that could take us to the stars, it’s easy to get excited. But the demons are in the details, and when you look at the actual article things look far less promising.

Continue reading “NASA Engineer Has A Great Idea for a High-Speed Spacedrive. Too Bad it Violates the Laws of Physics”Uh oh, the EMDrive Could be Getting Its “Thrust” From Cables and Earth’s Magnetic Field

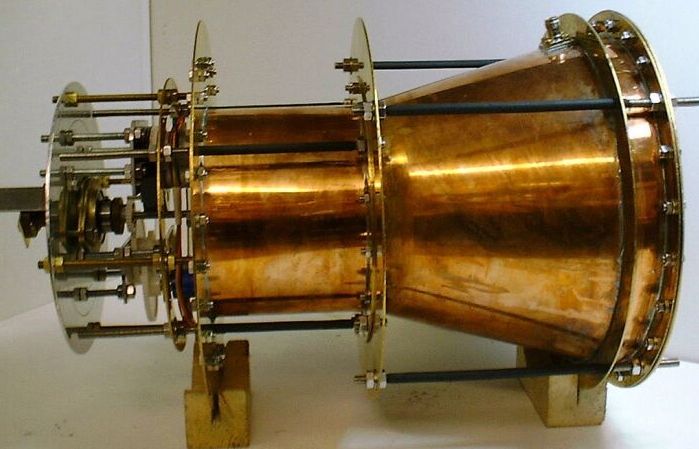

Ever since NASA announced that they had created a prototype of the controversial Radio Frequency Resonant Cavity Thruster (aka. the EM Drive), any and all reported results have been the subject of controversy. Initially, any reported tests were the stuff of rumors and leaks, the results were treated with understandable skepticism. Even after the paper submitted by the Eagleworks team passed peer review, there have still been unanswered questions.

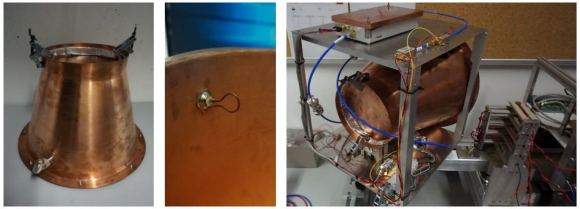

Hoping to address this, a team of physicists from TU Dresden – known as the SpaceDrive Project – recently conducted an independent test of the EM Drive. Their findings were presented at the 2018 Aeronautics and Astronautics Association of France’s Space Propulsion conference, and were less than encouraging. What they found, in a nutshell, was that much of the EM’s thrust could attributable to outside factors.

The results of their test were reported in a study titled “The SpaceDrive Project – First Results on EMDrive and Mach-Effect Thrusters“, which recently appeared online. The study was led by Martin Tajmar, an engineer from the Institute of Aerospace Engineering at TU Dresden, and included TU Dresden scientists Matthias Kößling, Marcel Weikert and Maxime Monette.

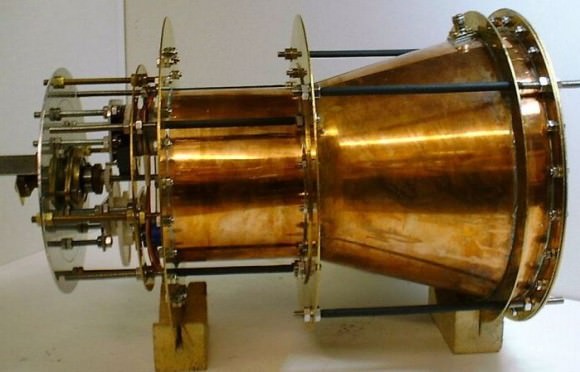

To recap, the EM Drive is a concept for an experimental space engine that came to the attention of the space community years ago. It consists of a hollow cone made of copper or other materials that reflects microwaves between opposite walls of the cavity in order to generate thrust. Unfortunately, this drive system is based on principles that violate the Conservation of Momentum law.

This law states that within a system, the amount of momentum remains constant and is neither created nor destroyed, but only changes through the action of forces. Since the EM Drive involves electromagnetic microwave cavities converting electrical energy directly into thrust, it has no reaction mass. It is therefore “impossible”, as far as conventional physics go.

As a result, many scientists have been skeptical about the EM Drive and wanted to see definitive evidence that it works. In response, a team of scientists at NASA’s Eagleworks Laboratories began conducting a test of the propulsion system. The team was led by Harold White, the Advanced Propulsion Team Lead for the NASA Engineering Directorate and the Principal Investigator for NASA’s Eagleworks lab.

Despite a report that was leaked in November of 2016 – titled “Measurement of Impulsive Thrust from a Closed Radio Frequency Cavity in Vacuum“ – the team never presented any official findings. This prompted the team led by Martin Tajmar to conduct their own test, using an engine that was built based on the same specifications as those used by the Eagleworks team.

In short, the TU Dresden team’s prototype consisted of a cone-shaped hollow engine set inside a highly shielded vacuum chamber, which they then fired microwaves at. While they found that the EM Drive did experience thrust, the detectable thrust may not have been coming from the engine itself. Essentially, the thruster exhibited the same amount of force regardless of which direction it was pointing.

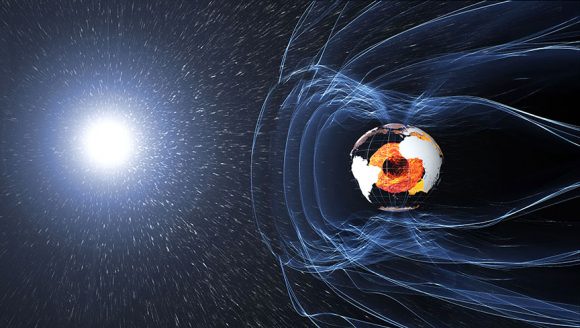

This suggested that the thrust was originating from another source, which they believe could be the result of interaction between engine cables and the Earth’s magnetic field. As they conclude in their report:

“First measurement campaigns were carried out with both thruster models reaching thrust/thrust-to– power levels comparable to claimed values. However, we found that e.g. magnetic interaction from twisted-pair cables and amplifiers with the Earth’s magnetic field can be a significant error source for EMDrives. We continue to improve our measurement setup and thruster developments in order to finally assess if any of these concepts is viable and if it can be scaled up.”

In other words, the mystery thrust reported by previous experiments may have been nothing more than an error. If true, it would explain how the “impossible EM Drive” was able to achieve small amounts of measurable thrust when the laws of physics claim it shouldn’t be. However, the team also emphasized that more testing will be needed before the EM Drive can be dismissed or validated with confidence.

Alas, it seems that the promise of being able to travel to the Moon in just four hours, to Mars in 70 days, and to Pluto in 18 months – all without the need for propellant – may have to wait. But rest assured, many other experimental technologies are being tested that could one day allow us to travel within our Solar System (and beyond) in record time. And additional tests will be needed before the EM Drive can be written off as just another pipe dream.

The team also conducted their own test of the Mach-Effect Thruster, another concept that is considered to be unlikely by many scientists. The team reported more favorable results with this concept, though they indicated that more research is needed here as well before anything can be conclusively said. You can learn more about the team’s test results for both engines by reading their report here.

And be sure to check out this video by Scott Manley, who explains the latest test and its results

Further Reading: ResearchGate, Phys.org

Weekly Space Hangout – November 25, 2016: Dean Regas and his “Facts from Space”

Host: Fraser Cain (@fcain)

Special Guest:

Dean Regas has been the Astronomer for the Cincinnati Observatory since 2000. He is the co-host of Star Gazers (airing on PBS stations around the world), a Contributing Editor to Sky and Telescope Magazine, and a contributor to Astronomy Magazine. Dean is the author of the new book, “Facts from Space! From Super-Secret Spacecraft to Volcanoes in Outer Space, Extraterrestrial Facts to Blow Your Mind!”

Guests:

Paul M. Sutter (pmsutter.com / @PaulMattSutter)

Yoav Landsman (@MasaCritit)

Their stories this week:

Cause of Schiaparelli’s crash: 1 second glitch

Let me tell you what I think of the EM Drive

We use a tool called Trello to submit and vote on stories we would like to see covered each week, and then Fraser will be selecting the stories from there. Here is the link to the Trello WSH page (http://bit.ly/WSHVote), which you can see without logging in. If you’d like to vote, just create a login and help us decide what to cover!

If you would like to join the Weekly Space Hangout Crew, visit their site here and sign up. They’re a great team who can help you join our online discussions!

If you would like to sign up for the AstronomyCast Solar Eclipse Escape, where you can meet Fraser and Pamela, plus WSH Crew and other fans, visit our site linked above and sign up!

We record the Weekly Space Hangout every Friday at 12:00 pm Pacific / 3:00 pm Eastern. You can watch us live on Universe Today, or the Universe Today YouTube page<

Was Physics Really Violated By EM Drive In “Leaked” NASA Paper?

Ever since NASA announced that they had created a prototype of the controversial Radio Frequency Resonant Cavity Thruster (aka. the EM Drive), any and all reported results have been the subject of controversy. And with most of the announcements taking the form of “leaks” and rumors, all reported developments have been naturally treated with skepticism.

And yet, the reports keep coming. The latest alleged results come from the Eagleworks Laboratories at the Johnson Space Center, where a “leaked” report revealed that the controversial drive is capable of generating thrust in a vacuum. Much like the critical peer-review process, whether or not the engine can pass muster in space has been a lingering issue for some time.

Given the advantages of the EM Drive, it is understandable that people want to see it work. Theoretically, these include the ability to generate enough thrust to fly to the Moon in just four hours, to Mars in 70 days, and to Pluto in 18 months, and the ability to do it all without the need for propellant. Unfortunately, the drive system is based on principles that violate the Conservation of Momentum law.

This law states that within a system, the amount of momentum remains constant and is neither created nor destroyed, but only changes through the action of forces. Since the EM Drive involves electromagnetic microwave cavities converting electrical energy directly into thrust, it has no reaction mass. It is therefore “impossible”, as far as conventional physics go.

The report, titled “Measurement of Impulsive Thrust from a Closed Radio Frequency Cavity in Vacuum“, was apparently leaked in early November. It’s lead author is predictably Harold White, the Advanced Propulsion Team Lead for the NASA Engineering Directorate and the Principal Investigator for NASA’s Eagleworks lab.

As he and his colleagues (allegedly) report in the paper, they completed an impulsive thrust test on a “tapered RF test article”. This consisted of a forward and reverse thrust phase, a low thrust pendulum, and three thrust tests at power levels of 40, 60 and 80 watts. As they stated in the report:

“It is shown here that a dielectrically loaded tapered RF test article excited in the TM212 mode at 1,937 MHz is capable of consistently generating force at a thrust level of 1.2 ± 0.1 mN/kW with the force directed to the narrow end under vacuum conditions.”

To be clear, this level of thrust to power – 1.2. millinewtons per kilowatt – is quite insignificant. In fact, the paper goes on to place these results in context, comparing them to ion thrusters and laser sail proposals:

“The current state of the art thrust to power for a Hall thruster is on the order of 60 mN/kW. This is an order of magnitude higher than the test article evaluated during the course of this vacuum campaign… The 1.2 mN/kW performance parameter is two orders of magnitude higher than other forms of ‘zero propellant’ propulsion such as light sails, laser propulsion and photon rockets having thrust to power levels in the 3.33-6.67 [micronewton]/kW (or 0.0033 – 0.0067 mN/kW) range.”

Currently, ion engines are considered the most fuel-efficient form of propulsion. However, they are notoriously slow compared to conventional, solid-propellant thrusters. To offer some perspective, NASA’s Dawn mission relied on a xenon-ion engine that had a thrust to power generation of 90 millinewtons per kilowatt. Using this technology, it took the probe almost four years to travel from Earth to the asteroid Vesta.

The concept of direct-energy (aka. laser sails), by contrast, requires very little thrust since it involves wafer-sized craft – tiny probes which weight about a gram and carry all their instruments they need in the form of chips. This concept is currently being explored for the sake of making the journey to neighboring planets and star systems within our own lifetimes.

Two good examples are the NASA-funded DEEP-IN interstellar concept that is being developed at UCSB, which attempts to use lasers to power a craft up to 0.25 the speed of light. Meanwhile, Project Starshot (part of Breakthrough Initiatives) is developing a craft which they claim will reach speeds of 20% the speed of light, and thus be able to make the trip to Alpha Centauri in 20 years.

Compared to these proposals, the EM Drive can still boast the fact that it does not require any propellant or an external power source. But based on these test results, the amount of power that would be needed to generate a significant amount of thrust would make it impractical. However, one should keep in mind that this low power test was designed to see if any thrust detected could be attributed to anomalies (none of which were detected).

The report also acknowledges that further testing will be necessary to rule out other possible causes, such as center of gravity (CG) shifts and thermal expansion. And if outside causes can again be ruled out, future tests will no doubt attempt to maximize performance to see just how much thrust the EM Drive is capable of generating.

But of course, this is all assuming that the “leaked” paper is genuine. Until NASA can confirm that these results are indeed real, the EM Drive will be stuck in controversy limbo. And while we’re waiting, check out this descriptive video by astronomer Scott Manley from the Armagh Observatory:

Further Reading: Science Alert

Carnival of Space #480

Welcome, come in to the 480th Carnival of Space! The Carnival is a community of space science and astronomy writers and bloggers, who submit their best work each week for your benefit. I’m Susie Murph, part of the team at Universe Today and CosmoQuest. So now, on to this week’s stories!

Continue reading “Carnival of Space #480”

NASA’s EM Drive Passes Peer Review, But Don’t Get Your Hopes Up

The “impossible” EM Drive (also known as the RF resonant cavity thruster) is one of those concepts that just won’t seem to die. Despite being subjected to a flurry of doubts and skepticism from the beginning that claim its too good to be true and violates the laws of physics, the EM Drive seems to be clearing all the hurdles placed in its way.

For years now, one of the most lingering comments has been that the technology has not passed peer-review. This has been the common retort whenever news of successful tests have been made. But, according to new rumors, the EM Drive recently did just that, as the paper that NASA submitted detailing the successful tests of their prototype has apparently passed the peer review process.

According to a story by International Business Times, the rumors were traced to Dr. José Rodal, and independent scientist who posted on the NASA Spaceflight Forum that the paper submitted by NASA Eagleworks Laboratories passed peer review and will appear in the Journal of Propulsion and Power, a publication maintained by the American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics (AIAA).

Now before anyone gets too excited, a quick reality check is necessary. At this time, everything said by Dr. Rodal has yet to be confirmed, and the comment has since been deleted. However, in his comment, Rodal did specify the paper would be titled “Measurement of Impulsive Thrust from a Closed Radio Frequency Cavity in Vacuum”.

He also named the papers authors, which includes Harold White – the Advanced Propulsion Team Lead for the Johnson Space Center’s Advanced Propulsion Physics Laboratory (aka. Eagleworks). Paul March was also named, another member of Eagleworks and someone who is associated with past tests.

On top of all that, the IB Times story indicated that he also posted information that appeared to be taken from the paper’s abstract:

“Thrust data in mode shape TM212 at less than 8106 Torr environment, from forward, reverse and null tests suggests that the system is consistently performing with a thrust to power ratio of 1.2 +/- 0.1 mN/Kw ()”.

But even if the rumor is true, there are other things that need to be taken into account. For instance, the peer-review process usually means that an independent panel of experts reviewed the work and determined that it is sufficient to merit further consideration. It does not mean the conclusions reached are correct, or that they won’t be subject to contradiction by follow-up investigations.

However, we may not have to wait long before the next test to happen. Guido Fetta is the CEO of Cannae Inc., the inventor of the Cannae Drive (which is based on Shawyer’s design). As he announced on August 17th of this year, the Cannae engine would be launched into space on board a 6U CubeSat in order to conduct tests in orbit.

As Fetta stated on their website, Cannae has formed a new company (Theseus Space Inc.) to commercialize their thruster technology, and will use this deployment to see if the Cannae drive can generate thrust in a vacuum:

“Theseus is going to be launching a demo cubesat which will use Cannae thruster technology to maintain an orbit below a 150 mile altitude. This cubesat will maintain its extreme LEO altitude for a minimum duration of 6 months. The primary mission objective is to demonstrate our thruster technology on orbit. Secondary objectives for this mission include orbital altitude and inclination changes performed by the Cannae-thruster technology.”

By remaining in orbit for six months, the company will have ample time to see if the satellite is experiencing thrust without the need for propellant. While no launch date has been selected yet, it is clear that Fetta wants to move forward with the launch as soon as possible.

And as David Hambling of Popular Mechanics recently wrote, Fetta is not alone in wanting to get orbital tests underway. A team of engineers in China is also hoping to test their design of the EM Drive in space, and Shawyer himself wants to complete this phase before long. One can only hope their drives all prove equal to the enterprise!

While this could be an important milestone for the EM Drive, it still has a long way to go before NASA and other space agencies consider using them. So we’re still a long away from spacecraft that can send a crewed mission to Mars in 70 days (or one to Pluto in just 18 months).

Further Reading: Emdrive.com, Popular Mechanics, IB Times

We Explored Pluto, Now Let’s Explore The Nearest Star!

On July 14th, 2015, the New Horizons space probe made history when it became the first spacecraft to conduct a flyby of the dwarf planet of Pluto. Since that time, it has been making its way through the Kuiper Belt, on its way to joining Voyager 1 and 2 in interstellar space. With this milestone reached, many are wondering where we should send our spacecraft next.

Naturally, there are those who recommend we set our sights on our nearest star – particularly proponents of interstellar travel and exoplanet hunters. In addition to being Earth’s immediate neighbor, there is the possibility of one or more exoplanets in this system. Confirming the existence of exoplanets would be one of the main reasons to go. But more than that, it would be a major accomplishment!

Continue reading “We Explored Pluto, Now Let’s Explore The Nearest Star!”