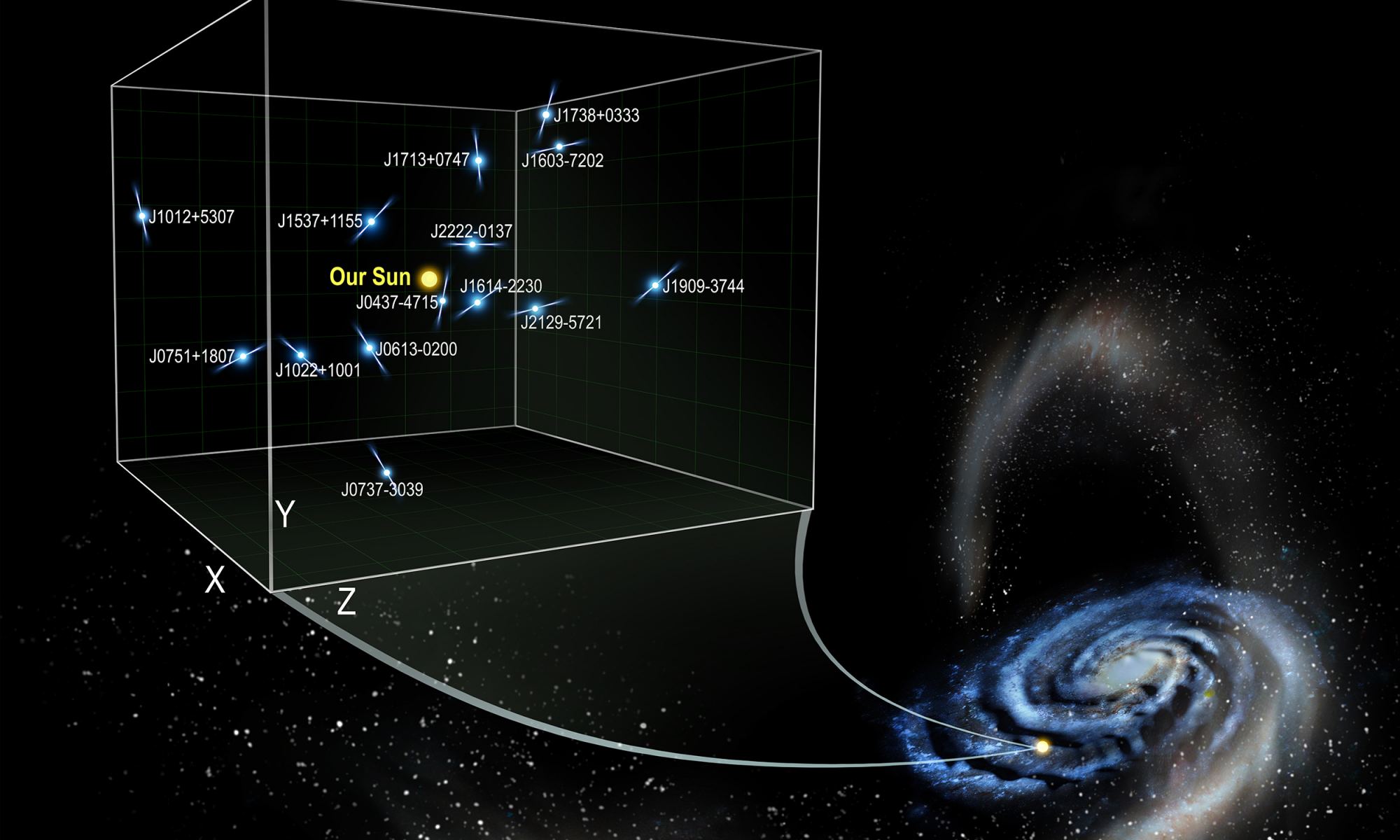

As our Sun moves along its orbit in the Milky Way, it is gravitationally tugged by nearby stars, nebulae, and other masses. Our galaxy is not a uniform distribution of mass, and our Sun experiences small accelerations in addition to its overall orbital motion. Measuring those small tugs has been nearly impossible, but a new study shows how it can be done.

Continue reading “Astronomers can use Pulsars to Measure Tiny Changes of Acceleration Within the Milky Way, Scanning Internally for Dark Matter and Dark Energy”What Would a Camera on a Breakthrough Starshot Spacecraft See if it’s Going at High Velocity?

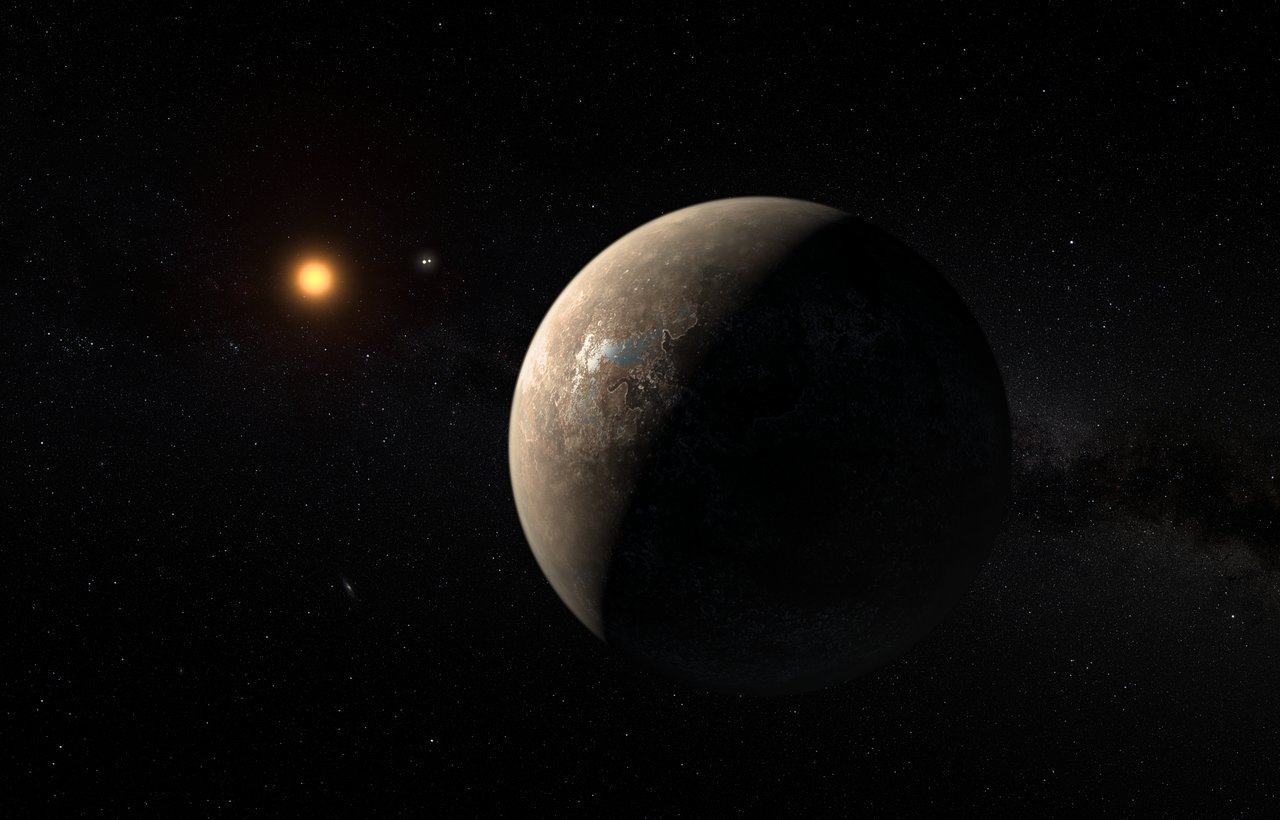

In April of 2016, Russian billionaire Yuri Milner announced the creation of Breakthrough Starshot. As part of his non-profit scientific organization (known as Breakthrough Initiatives), the purpose of Starshot was to design a lightsail nanocraft that would be capable of achieving speeds of up to 20% the speed of light and reaching the nearest star system – Alpha Centauri (aka. Rigel Kentaurus) – within our lifetimes.

At this speed – roughly 60,000 km/s (37,282 mps) – the probe would be able to reach Alpha Centauri in 20 years, where it could then capture images of the star and any planets orbiting it. But according to a recent article by Professor Bing Zhang, an astrophysicist from the University of Nevada, researchers could get all kinds of valuable data from Starshot and similar concepts long before they ever reached their destination.

The article appeared in The Conversation under the title “Observing the universe with a camera traveling near the speed of light“. The article was a follow-up to a study conducted by Prof. Zhang and Kunyang Li – a graduate student from the Center for Relativistic Astrophysics at the Georgia Institute of Technology – that appeared in The Astrophysical Journal (titled “Relativistic Astronomy“).

To recap, Breakthrough Starshot seeks to leverage recent technological developments to mount an interstellar mission that will reach another star within a single generation. The spacecraft would consist of an ultra-light nanocraft and a lightsail, the latter of which would accelerated by a ground-based laser array up to speeds of hundreds of kilometers per second.

Such a system would allow the tiny spacecraft to conduct a flyby mission of Alpha Centauri in about 20 years after it is launched, which could then beam home images of possible planets and other scientific data (such as analysis of magnetic fields). Recently, Breakthrough Starshot held an “industry day” where they submitted a Request For Proposals (RFP) to potential bidders to build the laser sail.

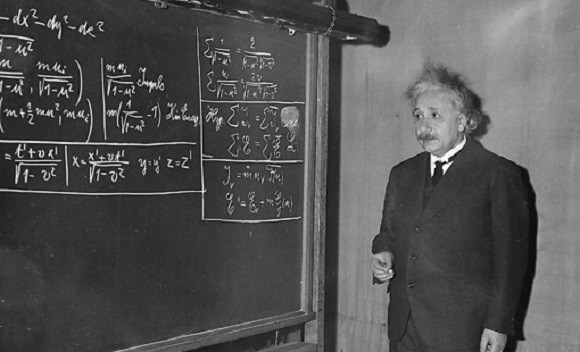

According to Zhang, a lightsail-driven nanocraft traveling at a portion of the speed of light would also be a good way to test Einstein’s theory of Special Relativity. Simply put, this law states that the speed of light in a vacuum is constant, regardless of the inertial reference frame or motion of the source. In short, such a spacecraft would be able to take advantage of the features of Special Relativity and provide a new mode to study astronomy.

Based on Einstein’s theory, different objects in different “rest frames” would have different measures of the lengths of space and time. In this sense, an object moving at relativistic speeds would view distant astronomical objects differently as light emissions from these objects would be distorted. Whereas objects in front of the spacecraft would have the wavelength of their light shortened, objects behind it would have them lengthened.

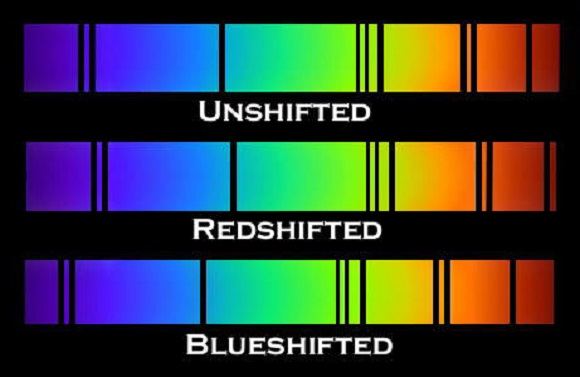

This phenomenon, known as the “Doppler Effect”, results in light being shifted towards the blue end (“blueshift”) or the red end (“redshift”) of the spectrum for approaching and retreating objects, respectively. In 1929, astronomer Edwin Hubble used redshift measurements to determine that distant galaxies were moving away from our own, thus demonstrating that the Universe was in a state of expansion.

Because of this expansion (known as the Hubble Expansion), much of the light in the Universe is redshifted and only measurable in difficult-to-observe infrared wavelengths. But for a camera moving at relativistic speeds, according to Prof. Zhang, this redshifted light would become bluer since the motion of the camera would counteract the effects of cosmic expansion.

This effect, known as “Doppler boosting”, would cause the faint light from the early Universe to be amplified and allow distant objects to be studied in more detail. In this respect, astronomers would be able to study some of the earliest objects in the known Universe, which would offer more clues as to how it evolved over time. As Prof. Zhang explained to Universe Today via email, this would allow for some unique opportunities to test Special Relativity:

“In the rest frame of the camera, the emission of the objects in the hemisphere of the camera motion is blue-shifted. For bright objects with detailed spectral observations from the ground, one can observe them in flight. By comparing their blue-shifted flux at a specific blue-shifted frequency with the flux of the corresponding (de-blueshifted) frequency on the ground, one can precisely test the Doppler boosting prediction in Special Relativity.”

In addition, the frequency and intensity of light – and also the size of distant objects – would also change as far as the observer was concerned. In this respect, the camera would act as a lens and a wide-field camera, magnifying the amount of light it collects and letting astronomers observe more objects within the same field of view. By comparing the observations collected by the camera to those collected by a camera from the ground, astronomers could also test the probe’s Lorentz Factor.

This factor indicates how time, length, and relativistic mass change for an object while that object is moving, which is another prediction of Special Relativity. Last, but not least, Prof. Zhang indicates that probes traveling at relativistic speeds would not need to be sent to any specific destination in order to conduct these tests. As he explained:

“The concept of “relativistic astronomy” is that one does not really need to send the cameras to specific star systems. No need to aim (e.g. to Alpha Centauri system), no need to decelerate. As long as the signal can be transferred back to earth, one can learn a lot of things. Interesting targets include high-redshift galaxies, active galactic nuclei, gamma-ray bursts, and even electromagnetic counterparts of gravitational waves.”

However, there are some drawbacks to this proposal. For starters, the technology behind Starshot is all about accomplishing the dream of countless generations – i.e. reaching another star system (in this case, Alpha Centauri) – within a single generation.

And as Professor Abraham Loeb – the Frank B. Baird Jr. Professor of Science at Harvard University and the Chair and the Breakthrough Starshot Committee – told Universe Today via email, what Prof. Zhang is proposing can be accomplished by other means:

>“Indeed, there are benefits to having a camera move near the speed of light toward faint sources, such as the most distant dwarf galaxies in the early universe. But the cost of launching a camera to the required speed would be far greater than building the next generation of large telescopes which will provide us with a similar sensitivity. Similarly, the goal of testing special relativity can be accomplished at a much lower cost.”

Of course, it will be many years before a project like Starshot can be mounted, and many challenges need to be addressed in the meantime. But it is exciting to know that in meantime, scientific applications can be found for such a mission that go beyond exploration. In a few decades, when the mission begins to make the journey to Alpha Centauri, perhaps it will also be able to conduct tests on Special Relativity and other physical laws while in transit.

Further Reading: The Conversation, The Astrophysical Journal

What is the Radial Velocity Method?

Welcome back to our series on Exoplanet-Hunting methods! Today, we look at another widely-used and popular method of exoplanet detection, known as the Radial Velocity (aka. Doppler Spectroscopy) Method.

The hunt for extra-solar planets sure has heated up in the past decade or so! Thanks to improvements made in instrumentation and methodology, the number of exoplanets discovered (as of December 1st, 2017) has reached 3,710 planets in 2,780 star systems, with 621 system boasting multiple planets. Unfortunately, due to the limits astronomers are forced to contend with, the vast majority have been discovered using indirect methods.

When it comes to these indirect methods, one of the most popular and effective is the Radial Velocity Method – also known as Doppler Spectroscopy. This method relies on observing the spectra stars for signs of “wobble”, where the star is found to be moving towards and away from Earth. This movement is caused by the presence of planets, which exert a gravitational influence on their respective sun.

Do Stars Move? Tracking Their Movements Across the Sky

The night sky, is the night sky, is the night sky. The constellations you learned as a child are the same constellations that you see today. Ancient people recognized these same constellations. Oh sure, they might not have had the same name for it, but essentially, we see what they saw.

But when you see animations of galaxies, especially as they come together and collide, you see the stars buzzing around like angry bees. We know that the stars can have motions, and yet, we don’t see them moving?

How fast are they moving, and will we ever be able to tell?

Stars, of course, do move. It’s just that the distances are so great that it’s very difficult to tell. But astronomers have been studying their position for thousands of years. Tracking the position and movements of the stars is known as astrometry.

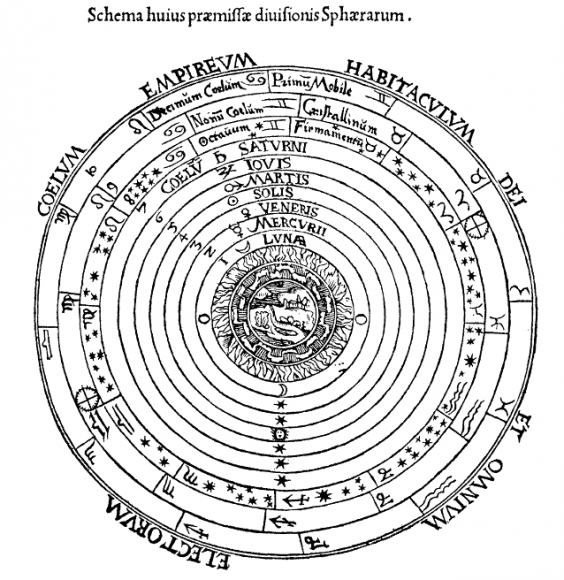

We trace the history of astrometry back to 190 BC, when the ancient Greek astronomer Hipparchus first created a catalog of the 850 brightest stars in the sky and their position. His student Ptolemy followed up with his own observations of the night sky, creating his important document: the Almagest.

In the Almagest, Ptolemy laid out his theory for an Earth-centric Universe, with the Moon, Sun, planets and stars in concentric crystal spheres that rotated around the planet. He was wrong about the Universe, of course, but his charts and tables were incredibly accurate, measuring the brightness and location of more than 1,000 stars.

A thousand years later, the Arabic astronomer Abd al-Rahman al-Sufi completed an even more detailed measurement of the sky using an astrolabe.

One of the most famous astronomers in history was the Danish Tycho Brahe. He was renowned for his ability to measure the position of stars, and built incredibly precise instruments for the time to do the job. He measured the positions of stars to within 15 to 35 arcseconds of accuracy. Just for comparison, a human hair, held 10 meters away is an arcsecond wide.

Also, I’m required to inform you that Brahe had a fake nose. He lost his in a duel, but had a brass replacement made.

In 1807, Friedrich Bessel was the first astronomer to measure the distance to a nearby star 61 Cygni. He used the technique of parallax, by measuring the angle to the star when the Earth was on one side of the Sun, and then measuring it again 6 months later when the Earth was on the other side.

Over the course of this period, this relatively closer star moves slightly back and forth against the more distant background of the galaxy.

And over the next two centuries, other astronomers further refined this technique, getting better and better at figuring out the distance and motions of stars.

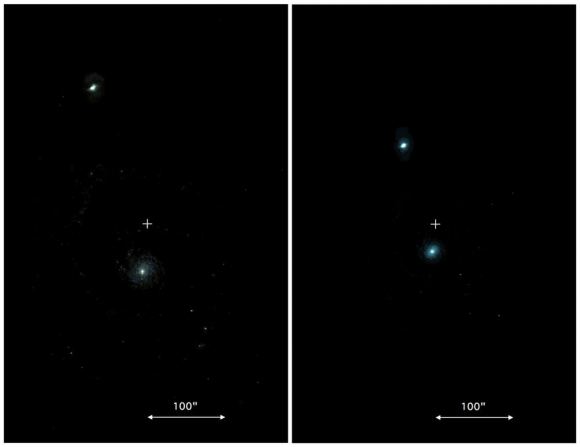

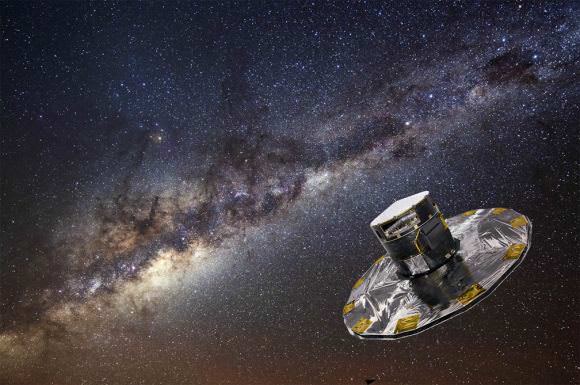

But to really track the positions and motions of stars, we needed to go to space. In 1989, the European Space Agency launched their Hipparcos mission, named after the Greek astronomer we talked about earlier. Its job was to measure the position and motion of the nearby stars in the Milky Way. Over the course of its mission, Hipparcos accurately measured 118,000 stars, and provided rough calculations for another 2 million stars.

That was useful, and astronomers have relied on it ever since, but something better has arrived, and its name is Gaia.

Launched in December 2013, the European Space Agency’s Gaia in is in the process of mapping out a billion stars in the Milky Way. That’s billion, with a B, and accounts for about 1% of the stars in the galaxy. The spacecraft will track the motion of 150 million stars, telling us where everything is going over time. It will be a mind bending accomplishment. Hipparchus would be proud.

With the most precise measurements, taken year after year, the motions of the stars can indeed be calculated. Although they’re not enough to see with the unaided eye, over thousands and tens of thousands of years, the positions of the stars change dramatically in the sky.

The familiar stars in the Big Dipper, for example, look how they do today. But if you go forward or backward in time, the positions of the stars look very different, and eventually completely unrecognizable.

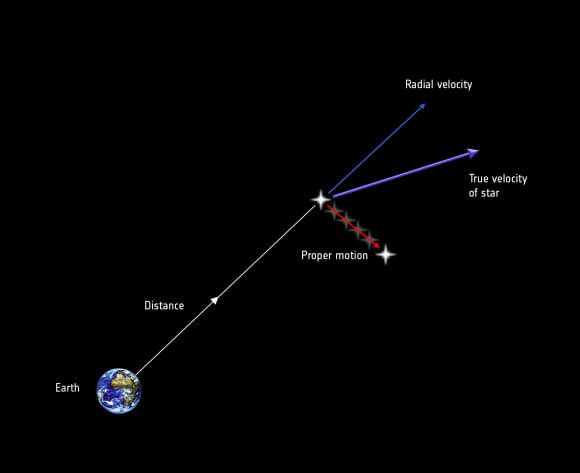

When a star is moving sideways across the sky, astronomers call this “proper motion”. The speed a star moves is typically about 0.1 arc second per year. This is almost imperceptible, but over the course of 2000 years, for example, a typical star would have moved across the sky by about half a degree, or the width of the Moon in the sky.

The star with the fastest proper motion that we know of is Barnard’s star, zipping through the sky at 10.25 arcseconds a year. In that same 2000 year period, it would have moved 5.5 degrees, or about 11 times the width of your hand. Very fast.

When a star is moving toward or away from us, astronomers call that radial velocity. They measure this by calculating the doppler shift. The light from stars moving towards us is shifted towards the blue side of the spectrum, while stars moving away from us are red-shifted.

Between the proper motion and redshift, you can get a precise calculation for the exact path a star is moving in the sky.

We know, for example, that the dwarf star Hipparcos 85605 is moving rapidly towards us. It’s 16 light-years away right now, but in the next few hundred thousand years, it’s going to get as close as .13 light-years away, or about 8,200 times the distance from the Earth to the Sun. This won’t cause us any direct effect, but the gravitational interaction from the star could kick a bunch of comets out of the Oort cloud and send them down towards the inner Solar System.

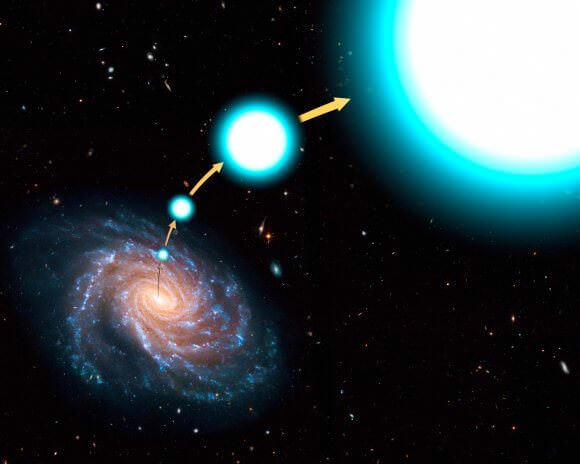

The motions of the stars is fairly gentle, jostling through gravitational interactions as they orbit around the center of the Milky Way. But there are other, more catastrophic events that can make stars move much more quickly through space.

When a binary pair of stars gets too close to the supermassive black hole at the center of the Milky Way, one can be consumed by the black hole. The other now has the velocity, without the added mass of its companion. This gives it a high-velocity kick. About once every 100,000 years, a star is kicked right out of the Milky Way from the galactic center.

Another situation can happen where a smaller star is orbiting around a supermassive companion. Over time, the massive star bloats up as supergiant and then detonates as a supernova. Like a stone released from a sling, the smaller star is no longer held in place by gravity, and it hurtles out into space at incredible speeds.

Astronomers have detected these hypervelocity stars moving at 1.1 million kilometers per hour relative to the center of the Milky Way.

All of the methods of stellar motion that I talked about so far are natural. But can you imagine a future civilization that becomes so powerful it could move the stars themselves?

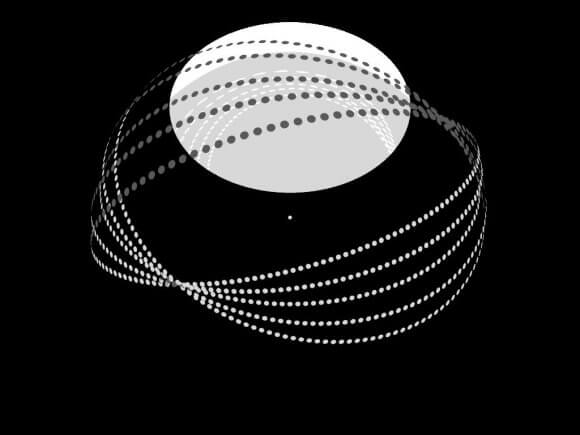

In 1987, the Russian astrophysicist Leonid Shkadov presented a technique that could move a star over vast lengths of time. By building a huge mirror and positioning it on one side of a star, the star itself could act like a thruster.

Photons from the star would reflect off the mirror, imparting momentum like a solar sail. The mirror itself would be massive enough that its gravity would attract the star, but the light pressure from the star would keep it from falling in. This would create a slow but steady pressure on the other side of the star, accelerating it in whatever direction the civilization wanted.

Over the course of a few billion years, a star could be relocated pretty much anywhere a civilization wanted within its host galaxy.

This would be a true Type III Civilization. A vast empire with such power and capability that they can rearrange the stars in their entire galaxy into a configuration that they find more useful. Maybe they arrange all the stars into a vast sphere, or some kind of geometric object, to minimize transit and communication times. Or maybe it makes more sense to push them all into a clean flat disk.

Amazingly, astronomers have actually gone looking for galaxies like this. In theory, a galaxy under control by a Type III Civilization should be obvious by the wavelength of light they give off. But so far, none have turned up. It’s all normal, natural galaxies as far as we can see in all directions.

For our short lifetimes, it appears as if the sky is frozen. The stars remain in their exact positions forever, but if you could speed up time, you’d see that everything is in motion, all the time, with stars moving back and forth, like airplanes across the sky. You just need to be patient to see it.

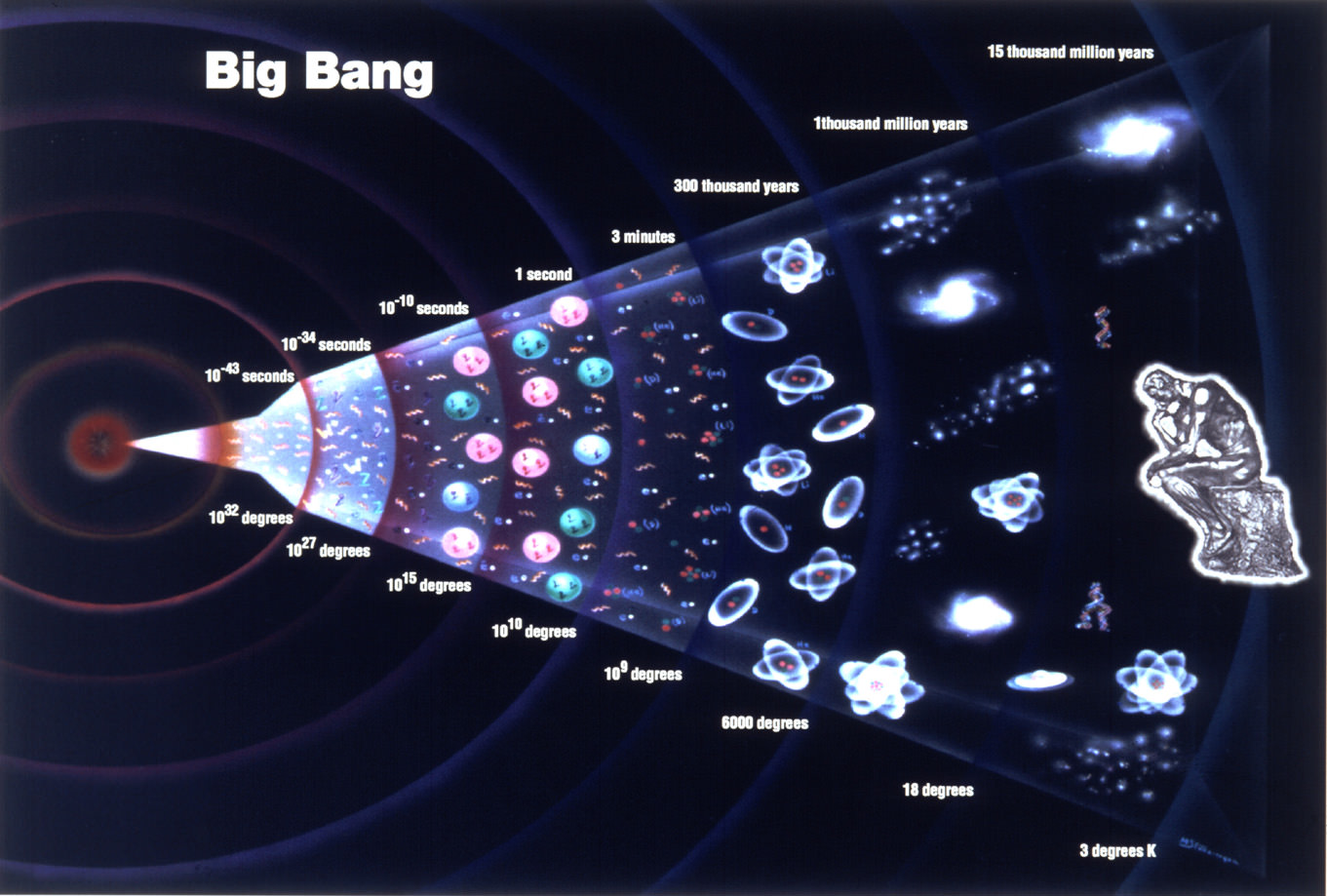

Big Bang Theory: Evolution of Our Universe

How was our Universe created? How did it come to be the seemingly infinite place we know of today? And what will become of it, ages from now? These are the questions that have been puzzling philosophers and scholars since the beginning the time, and led to some pretty wild and interesting theories. Today, the consensus among scientists, astronomers and cosmologists is that the Universe as we know it was created in a massive explosion that not only created the majority of matter, but the physical laws that govern our ever-expanding cosmos. This is known as The Big Bang Theory.

For almost a century, the term has been bandied about by scholars and non-scholars alike. This should come as no surprise, seeing as how it is the most accepted theory of our origins. But what exactly does it mean? How was our Universe conceived in a massive explosion, what proof is there of this, and what does the theory say about the long-term projections for our Universe?

The basics of the Big Bang theory are fairly simple. In short, the Big Bang hypothesis states that all of the current and past matter in the Universe came into existence at the same time, roughly 13.8 billion years ago. At this time, all matter was compacted into a very small ball with infinite density and intense heat called a Singularity. Suddenly, the Singularity began expanding, and the universe as we know it began.

Continue reading “Big Bang Theory: Evolution of Our Universe”Podcast: Dopler Effect

You know how a police siren changes sound when it passes by you? That’s the doppler effect. It works for sound waves and it works for light waves. Astronomers use the doppler effect to study the motion of objects across the Universe, from nearby extrasolar planets to the expansion of distant galaxies.

Click here to download the episode.

Or subscribe to: astronomycast.com/podcast.xml with your podcatching software.