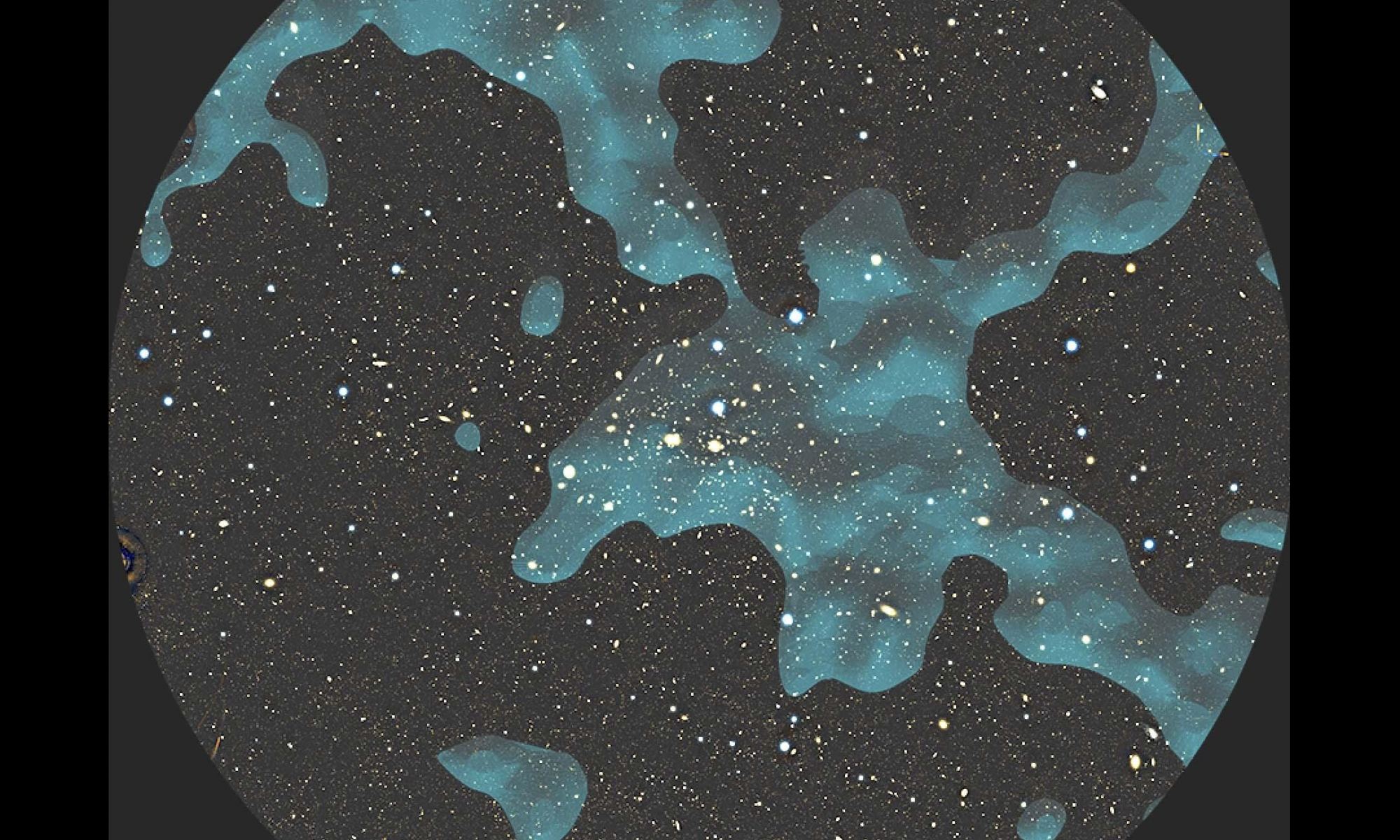

According to our predominant cosmological models, Dark Matter makes up the majority of mass in the Universe (roughly 85%). While it is not detectable in visible light, its influence can be seen based on how it causes matter to form large-scale structures in our Universe. Based on ongoing observations, astronomers have determined that Dark Matter structures are filamentary, consisting of long, thin strands. For the first time, using the Subaru Telescope, a team of astronomers directly detected Dark Matter filaments in a massive galaxy cluster, providing new evidence to test theories about the evolution of the Universe.

Continue reading ““Seeing” the Dark Matter Web That Surrounds the Coma Cluster”Have We Seen the First Glimpse of Supermassive Dark Stars?

A recent study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS) examines what are known as dark stars, which are estimated to be much larger than our Sun, are hypothesized to have existed in the early universe, and are allegedly powered by the demolition of dark matter particles. This study was conducted using spectroscopic analysis from NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), and more specifically, the JWST Advanced Deep Extragalactic Survey (JADES), and holds the potential to help astronomers better understand dark stars and the purpose of dark matter, the latter of which continues to be an enigma for the scientific community, as well as how it could have contributed to the early universe.

Continue reading “Have We Seen the First Glimpse of Supermassive Dark Stars?”If Axions are Dark Matter, we've got new Hints About Where to Look for Them

If dark matter is out there, and it certainly seems to be, then what could it possibly be? That is perhaps the biggest mystery of dark matter. The only known particles that match the requirement of having mass and not interacting strongly with light are neutrinos. But neutrinos have low mass and zip through the cosmos at nearly the speed of light. They are a form of “hot” dark matter, so they don’t match the observed data that require dark matter to be “cold.” With neutrinos ruled out, cosmologists look toward various hypothetical particles we haven’t discovered, and perhaps the most popular of these are known as axions.

Continue reading “If Axions are Dark Matter, we've got new Hints About Where to Look for Them”Cosmic Dawn Holds the Answers to Many of Astronomy’s Greatest Questions

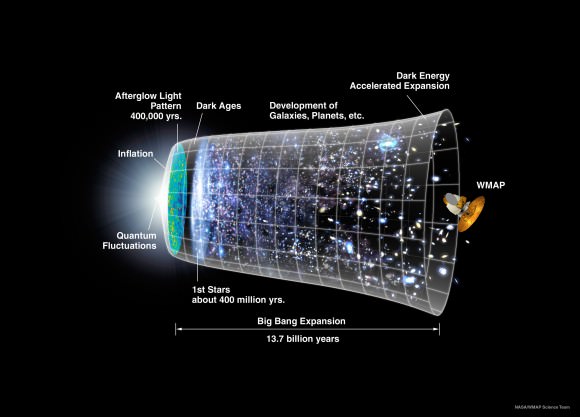

Thanks to the most advanced telescopes, astronomers today can see what objects looked like 13 billion years ago, roughly 800 million years after the Big Bang. Unfortunately, they are still unable to pierce the veil of the cosmic Dark Ages, a period that lasted from 370,000 to 1 billion years after the Big Bang, where the Universe was shrowded with light-obscuring neutral hydrogen. Because of this, our telescopes cannot see when the first stars and galaxies formed – ca., 100 to 500 million years after the Big Bang.

This period is known as the Cosmic Dawn and represents the “final frontier” of cosmological surveys to astronomers. This November, NASA’s next-generation James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) will finally launch to space. Thanks to its sensitivity and advanced infrared optics, Webb will be the first observatory capable of witnessing the birth of galaxies. According to a new study from the Université de Genève, Switzerland, the ability to see the Cosmic Dawn will provide answers to today’s greatest cosmological mysteries.

Continue reading “Cosmic Dawn Holds the Answers to Many of Astronomy’s Greatest Questions”CHIME Detected Over 500 Fast Radio Burst in its First Year, Providing new Clues to What’s Causing Them

Much like Dark Matter and Dark Energy, Fast Radio Burst (FRBs) are one of those crazy cosmic phenomena that continue to mystify astronomers. These incredibly bright flashes register only in the radio band of the electromagnetic spectrum, occur suddenly, and last only a few milliseconds before vanishing without a trace. As a result, observing them with a radio telescope is rather challenging and requires extremely precise timing.

Hence why the Dominion Radio Astrophysical Observatory (DRAO) in British Columbia launched the Canadian Hydrogen Intensity Mapping Experiment (CHIME) in 2017. Along with their partners at the National Radio Astronomy Observatory (NRAO), the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), the Perimeter Institute, and multiple universities, CHIME detected more than 500 FRBs in its first year of operation (and more than 1000 since it commenced operations)!

Continue reading “CHIME Detected Over 500 Fast Radio Burst in its First Year, Providing new Clues to What’s Causing Them”A new Method Simulates the Universe 1000 Times Faster

Cosmologists love universe simulations. Even models covering hundreds of millions of light years can be useful for understanding fundamental aspects of cosmology and the early universe. There’s just one problem – they’re extremely computationally intensive. A 500 million light year swath of the universe could take more than 3 weeks to simulate.. Now, scientists led by Yin Li at the Flatiron Institute have developed a way to run these cosmically huge models 1000 times faster. That 500 million year light year swath could then be simulated in 36 minutes.

Continue reading “A new Method Simulates the Universe 1000 Times Faster”Turns Out There Is No Actual Looking Up

Direction is something we humans are pretty accustomed to. Living in our friendly terrestrial environment, we are used to seeing things in term of up and down, left and right, forwards or backwards. And to us, our frame of reference is fixed and doesn’t change, unless we move or are in the process of moving. But when it comes to cosmology, things get a little more complicated.

For a long time now, cosmologists have held the belief that the universe is homogeneous and isotropic – i.e. fundamentally the same in all directions. In this sense, there is no such thing as “up” or “down” when it comes to space, only points of reference that are entirely relative. And thanks to a new study by researchers from the University College London, that view has been shown to be correct.

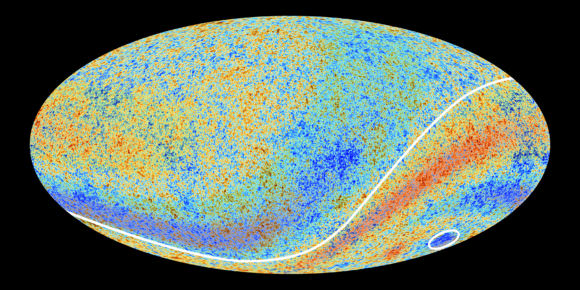

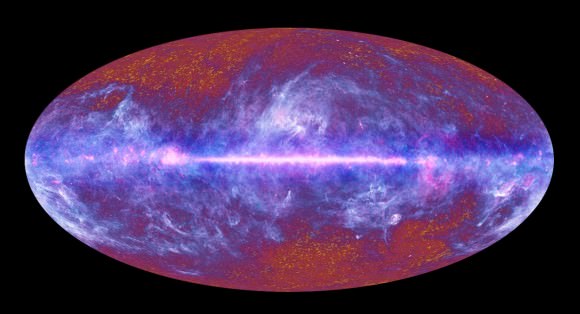

For the sake of their study, titled “How isotropic is the Universe?“, the research team used survey data of the Cosmic Microwave Background (CMB) – the thermal radiation left over from the Big Bang. This data was obtained by the ESA’s Planck spacecraft between 2009 and 2013.

The team then analyzed it using a supercomputer to determine if there were any polarization patterns that would indicate if space has a “preferred direction” of expansion. The purpose of this test was to see if one of the basic assumptions that underlies the most widely-accepted cosmological model is in fact correct.

The first of these assumptions is that the Universe was created by the Big Bang, which is based on the discovery that the Universe is in a state of expansion, and the discovery of the Cosmic Microwave Background. The second assumption is that space is homogenous and istropic, meaning that there are no major differences in the distribution of matter over large scales.

This belief, which is also known as the Cosmological Principle, is based partly on the Copernican Principle (which states that Earth has no special place in the Universe) and Einstein’s Theory of Relativity – which demonstrated that the measurement of inertia in any system is relative to the observer.

This theory has always had its limitations, as matter is clearly not evenly distributed at smaller scales (i.e. star systems, galaxies, galaxy clusters, etc.). However, cosmologists have argued around this by saying that fluctuation on the small scale are due to quantum fluctuations that occurred in the early Universe, and that the large-scale structure is one of homogeneity.

By looking for fluctuations in the oldest light in the Universe, scientists have been attempting to determine if this is in fact correct. In the past thirty years, these kinds of measurements have been performed by multiple missions, such as the Cosmic Background Explorer (COBE) mission, the Wilkinson Microwave Anisotropy Probe (WMAP), and the Planck spacecraft.

For the sake of their study, the UCL research team – led by Daniela Saadeh and Stephen Feeney – looked at things a little differently. Instead of searching for imbalances in the microwave background, they looked for signs that space could have a preferred direction of expansion, and how these might imprint themselves on the CMB.

As Daniela Saadeh – a PhD student at UCL and the lead author on the paper – told Universe Today via email:

“We analyzed the temperature and polarization of the cosmic microwave background (CMB), a relic radiation from the Big Bang, using data from the Planck mission. We compared the real CMB against our predictions for what it would look like in an anisotropic universe. After this search, we concluded that there is no evidence for these patterns and that the assumption that the Universe is isotropic on large scales is a good one.”

Basically, their results showed that there is only a 1 in 121 000 chance that the Universe is anisotropic. In other words, the evidence indicates that the Universe has been expanding in all directions uniformly, thus removing any doubts about their being any actual sense of direction on the large-scale.

And in a way, this is a bit disappointing, since a Universe that is not homogenous and the same in all directions would lead to a set of solutions to Einstein’s field equations. By themselves, these equations do not impose any symmetries on space time, but the Standard Model (of which they are part) does accept homogeneity as a sort of given.

These solutions are known as the Bianchi models, which were proposed by Italian mathematician Luigi Bianchi in the late 19th century. These algebraic theories, which can be applied to three-dimensional spacetime, are obtained by being less restrictive, and thus allow for a Universe that is anisotropic.

On the other hand, the study performed by Saadeh, Feeney, and their colleagues has shown that one of the main assumptions that our current cosmological models rest on is indeed correct. In so doing, they have also provided a much-needed sense of closer to a long-term debate.

“In the last ten years there has been considerable discussion around whether there were signs of large-scale anisotropy lurking in the CMB,” said Saadeh. “If the Universe were anisotropic, we would need to revise many of our calculations about its history and content. Planck high-quality data came with a golden opportunity to perform this health check on the standard model of cosmology and the good news is that it is safe.”

So the next time you find yourself looking up at the night sky, remember… that’s a luxury you have only while you’re standing on Earth. Out there, its a whole ‘nother ballgame! So enjoy this thing we call “direction” when and where you can.

And be sure to check out this animation produced by the UCL team, which illustrates the Planck mission’s CMB data: