Hosts: Fraser Cain and Scott Lewis

Astronomers: Gary Gonella, Roy Salisbury, Steven Coates, Tom Nathe, Stuart Foreman

Continue reading “Virtual Star Party – December 1, 2013 – Dying Comets, Smashing Galaxies and Cosmic Bees”

Is Comet ISON Dead? Astronomers Say It’s Likely After Icarus Sun-Grazing Stunt

Update, 9:55 pm EST: It’s a Thanksgiving miracle: apparently it now looks like ISON has actually survived!!

Alright we're calling it, and you heard it here first: We believe some small part of #ISON's nucleus has SURVIVED perihelion.

— Sungrazer Comets (@SungrazerComets) November 29, 2013

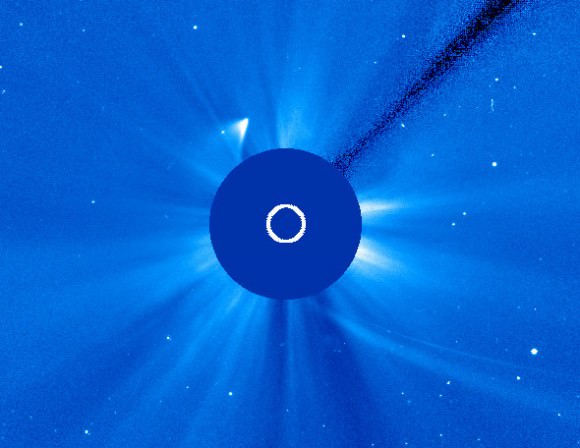

Update, 8:35 p.m. EST: Uncertainty about Comet ISON’s fate likely will persist for some time. Karl Battams just tweeted that after 2,000 sungrazing comet observations, he has never seen brightening in the same way that ISON (or its remains) appear to be doing right now. We’ll keep watching. Real-time images are available on this website.

Update, 6:30 p.m. EST: An excellent blog post from Phil Plait (who writes the Bad Astronomy blog on Slate) summarizes his take of the comet’s fate; debris (most likely, he says) continues to show up in images. An except: “It held together a long time, got very bright last night, faded this morning, then apparently fell apart. This isn’t surprising; we see comets disintegrate often enough as they round the Sun. ISON’s nucleus was only a couple of kilometers across at best, so it would have suffered under the Sun’s heat more than a bigger comet would have. Still, there’s more observing to do, and of course much data over which to pore.”

Update, 4:40 p.m. EST: On Twitter, the European Space Agency (quoting SOHO scientist Bernhard Fleck) said the comet is gone. Separately, the Naval Research Laboratory’s Karl Battams posted that he thinks recent observations show debris from ISON, but not a nucleus. Astronomers are still monitoring, however.

Update, 3:56 p.m. EST: Something has emerged from perihelion, but the experts are divided as to whether it’s leftovers of ISON’s tail, or the comet itself. Stay tuned.

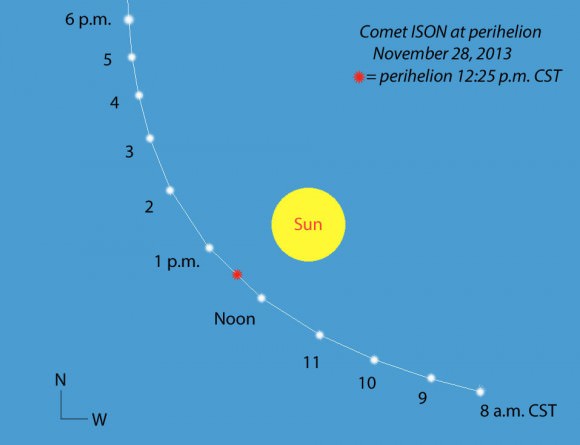

The fate of Comet C/2012 S1 ISON is uncertain. It made its closest approach to the sun today (Nov. 28) around 1:44 p.m. EST (6:44 p.m. UTC). As of Thursday night, what’s happening to the comet is still unclear, as observers try to keep up hopes for a good comet show in the next few weeks.

It will take a few more hours until NASA and other agencies can say for sure what the comet’s fate is. That said, there still is valuable science that can be performed if ISON has broken up — more details below the jump.

ISON coincided with American Thanksgiving, causing a lot of astronomers and journalists to work holiday hours while pundits made jokes about the comet being “roasted” along with the turkey. Meanwhile, amateur astronomer Stuart Atkinson — author of the Waiting for ISON blog — was among those eagerly awaiting the comet’s closest approach.

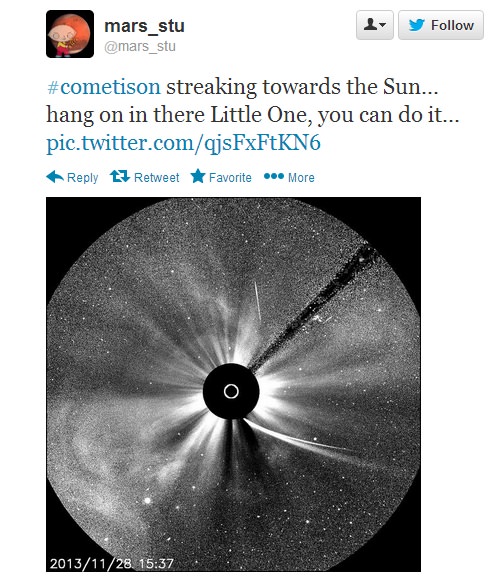

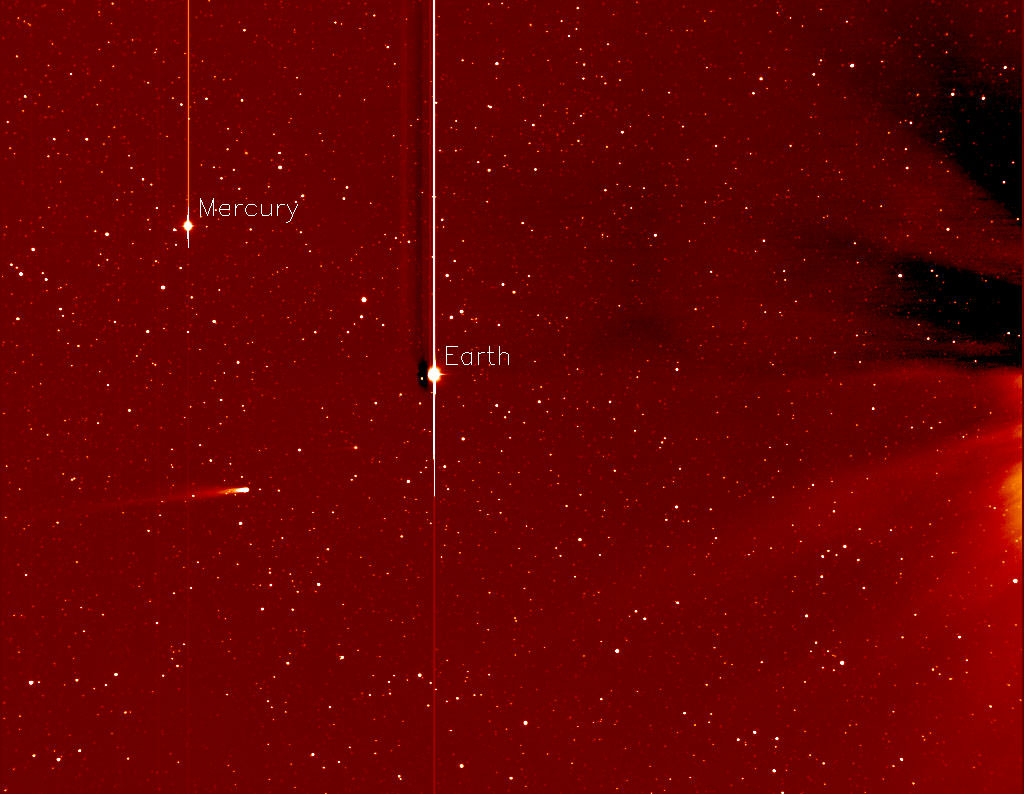

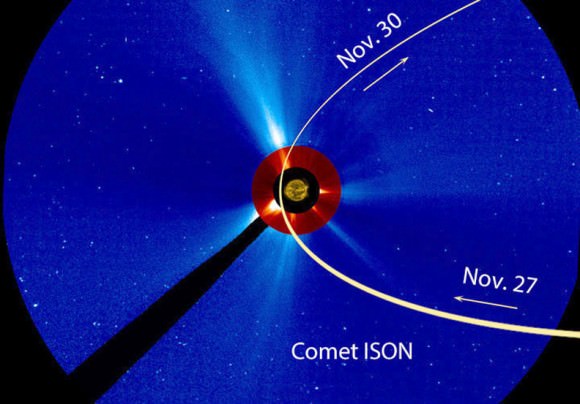

But as the comet made its closest approach, astronomers grew more and more skeptical than it had survived. Phil Plait (who writes the Bad Astronomy blog on Slate) pointed out that the comet’s nucleus appeared much dimmer than its tail in images from SOHO (Solar and Heliospheric Observatory), NASA’s sun-gazing spacecraft. This implied that the nucleus was disintegrating.

Plait and Karl Battams — a Naval Research Laboratory astrophysicist who operates the Sungrazing Comets Project — both participated in a NASA Google+ Hangout on ISON. As of about 2 p.m. EST (7 p.m. UTC), both said that they believe ISON is an “ex-comet”, although it will be a few more hours before scientists can say for sure.

The challenge is that the two spacecraft used to watch ISON swing around the sun — the Solar Dynamics Observatory and SOHO — are not necessarily designed to look for comets. Battams and Plait initially said that it sometimes take additional image processing to view information in it. more As time elapsed though, both expressed extreme skepticism that the comet survived.

Even if the comet is dead, Plait pointed out that scientists can still learn a lot from the remaining debris. ISON is believed to be a pristine example of bodies in the Oort Cloud, a vast body of small objects beyond the orbit of Neptune. Examining the dust in its debris trail could tell scientists more about the origins of the solar system.

“The fact that it’s broken up is really cool. There’s a lot we can learn from it and a lot we can get from it,” he said.

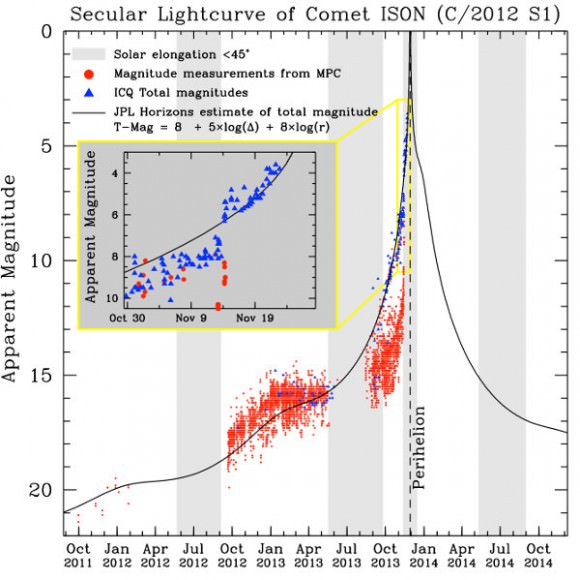

Battams added that ISON has been a very unpredictable comet, flaring up when people expected it would fade, and vice versa. “ISON is just weird. It has behaved unpredictably at times. When it’s done something strange, we spent some time scratching our heads, figuring out what is going on and we think we know what it’s doing … it then goes and does something different.”

Amid the waiting came the inevitable social media jokes (including science fiction and fantasy references.)

For others, the comet served as an inspiration for daring to be courageous.

ISON Watch: A Post-Perihelion Viewing Guide

“ISON Lives!!!”

“ISON R.I.P…”

Those are just some of the possible headlines that we’ve wrestled with this week, as Comet C/2012 S1 ISON approaches perihelion tomorrow evening. It’s been a rollercoaster ride of a week, and this sungrazing comet promises to keep us guessing right up until the very end.

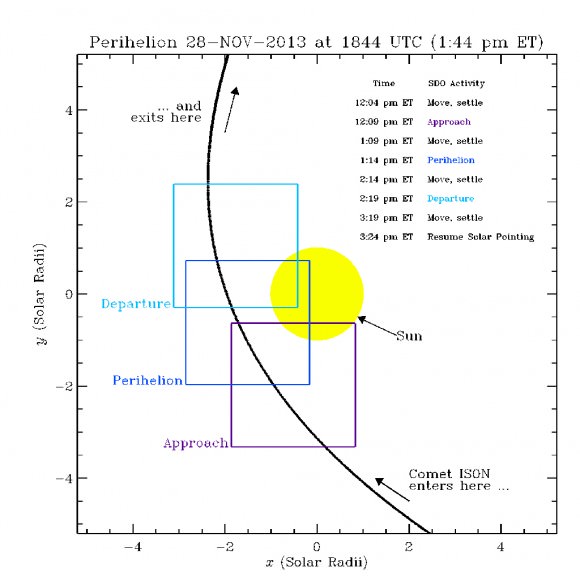

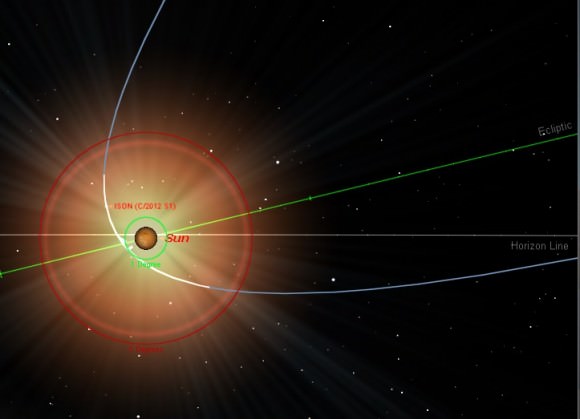

Comet ISON reaches perihelion on U.S. Thanksgiving Day Thursday, November 28th at around 18:44 Universal Time/ 1:44 PM Eastern Standard Time. ISON will pass 1.2 million kilometres from the surface of the Sun, just over eight times farther than Comet C/2011 W3 Lovejoy did in 2011, and about 38 times closer to the Sun than Mercury reaches at perihelion.

Earth-based observers essentially lost sight of ISON in the dawn twilight this past weekend, and there were fears that the comet might’ve disintegrated all together as it was tracked by NASA’s STEREO spacecraft. Troubling reports circulated early this week that emission rates for the comet had dropped while dust production had risen, possibly signaling that fragmentation of the nucleus was imminent. Certainly, this comet is full of surprises, and our observational experience with large sungrazing comets of this sort is pretty meager.

However, as ISON entered the field of view of the Solar and Heliospheric Observatory’s LASCO C3 camera earlier today it still appeared to have some game left in it. NASA’s Solar Dynamics Observatory will pick up ISON starting at around 17:09UT/12:09 PM EST tomorrow, and track it through its history-making perihelion passage for just over two hours until 19:09UT/2:19PM EST.

And just as with Comet Lovejoy a few years ago, all eyes will be glued to the webcast from NASA’s Solar Dynamics Observatory as ISON rounds the bend towards its date with destiny… don’t miss it!

Note: you can also follow ISON’s current progress as seen from SOHO at their website!

For over the past year since its discovery, pundits have pondered what is now the astronomical question of the approaching hour: just what is ISON going to do post-perihelion? Will it dazzle or fizzle? In this context, ISON has truly become “Schrödinger’s Comet,” both alive and dead in the minds of those who would attempt to divine its fate.

Recent estimates place ISON’s nucleus at between 950 and 1,250 metres in diameter. This is well above the 200 metre size that’s considered the “point of no return” for a comet passing this close to the Sun. But again, another key factor to consider is how well put together the nucleus of the comet is: a lumpy rubble pile may not hold up against the intense heat and the gravitational tug of the Sun!

But what are the current prospects for spotting ISON after its fiery perihelion passage?

If the comet holds together, reasonable estimates put its maximum brightness near perihelion at between magnitudes -3 and -5, in the range of the planet Venus at maximum brilliancy. ISON will, however, only stand 14’ arc minutes from the disk of the Sun (less than half its apparent diameter) at perihelion, and spying it will be a tough feat that should only be attempted by advanced observers.

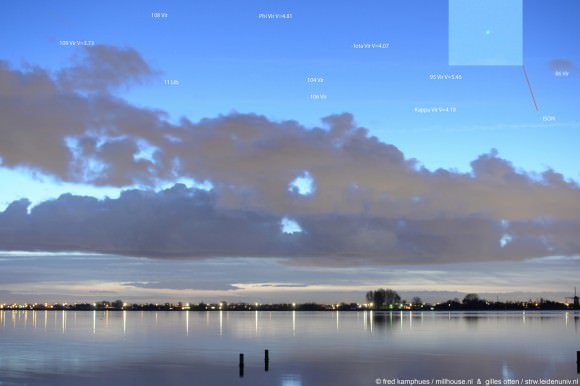

Note that for observers based at high northern latitudes “north of the 60,” the shallow angle of the ecliptic might just make it possible to spot Comet ISON low in the dawn after perihelion and before sunrise November 29th:

We’ve managed to see the planet Venus the day of solar conjunction during similar circumstances with the Sun just below the horizon while observing from North Pole, Alaska.

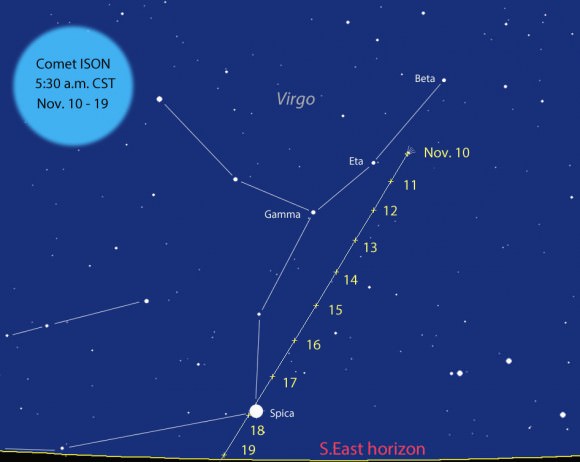

Most northern hemisphere observers may catch first sight of Comet ISON post-perihelion around the morning of December 1st. Look low to the east, about half an hour before local sunrise. Use binoculars to sweep back and forth on your morning comet dawn patrol. Note that on December 1st, Saturn, Mercury, and the slim waning crescent Moon will also perch nearby!

Comet ISON will rapidly gain elevation on successive mornings as it heads off to the northeast, but will also rapidly decrease in brightness as well. If current projections hold, ISON will dip back below magnitude 0 just a few days after perihelion, and back below naked eye visibility by late December. Observers may also be able to start picking it up low to the west at dusk by mid-December, but mornings will be your best bet.

Keep in mind, if ISON fizzles, this could become a “death-watch” for the remnants of the comet, as fragments that might only be visible with binoculars or a telescope follow its outward path. If this turns out to be the case, then the best views of the “Comet formerly known as ISON” have already occurred.

Another possible scenario is that the comet might fragment right around perihelion, leaving us with a brief but brilliant “headless comet,” similar to W3 Lovejoy back in late 2011. The forward light scattering angle for any comet is key to visibility, and in this aspect, ISON is just on the grim edge in terms of its potential to enter the annals of “great” comets, such as Comet Ikeya-Seki back in 1965.

ISON will then run nearly parallel to the 16 hour line in right ascension from south to north through the month of December as it crosses the celestial equator, headed for a date with the north celestial pole just past New Years Day, 2014.

Whether as fragments or whole, comets have to obey Sir Isaac and his laws of physics as they trace their elliptical path back out of the solar system. Keep in mind, a comet’s dust tail actually precedes it on its way outbound as the solar wind sweeps past, a counter-intuitive but neat concept we may just get to see in action soon.

Here are some key dates to watch for as ISON makes tracks across the northern hemisphere sky. Passages are noted near stars brighter than +5th magnitude and closer than one degree except as mentioned:

December 1st: ISON is grouped with Saturn, Mercury and the slim crescent Moon in the dawn.

December 2nd: Passes near the +4.9 magnitude star Psi Scorpii.

December 3rd: Passes into the constellation Ophiuchus.

December 5th: Passes near the +2.7 magnitude multiple star Yed Prior.

December 6th: Crosses into the constellation Serpens Caput.

December 8th: Crosses from south to north of the celestial equator.

December 15th: Passes into the constellation Hercules and near the +5th magnitude star Kappa Herculis.

December 17th: The Moon reaches Full, marking the middle of a week with decreased visibility for the comet.

December 19th: Passes into the constellation of Corona Borealis.

December 20th: Passes near the +4.8th magnitude star Xi Coronae Borealis.

December 22nd: Passes 5 degrees from the globular cluster M13. Photo op!

December 23rd: Crosses back into the constellation Hercules.

December 24th: Passes near the +3.9 magnitude star Tau Herculis.

December 26th: Comet ISON passes closest to Earth at 0.43 A.U. or 64 million kilometres distant, now moving with a maximum apparent motion of nearly 4 degrees a day.

December 26th: Crosses into the constellation Draco and becomes circumpolar for observers based at latitude 40 north.

December 28th: Passes the +2.7 magnitude star Aldhibain.

December 29th: Passes the +4.8 magnitude star 18 Draconis.

December 31st: Passes the 4.9 magnitude star 15 Draconis.

January 2nd: Crosses into the constellation Ursa Minor.

January 4th: Crosses briefly back into the constellation Draco.

January 6th: Crosses back into the constellation Ursa Minor.

January 7th: Crosses into Cepheus; passes within 2.5 degrees of Polaris and the North Celestial Pole.

And after what is (hopefully) a brilliant show, ISON will head back out into the depths of the solar system, perhaps never to return. Whatever the case turns out to be, observations of ISON will have produced some first-rate science… and no planets, popes or prophets will have been harmed in the process. And while those in the business of predicting doom will have moved on to the next apocalypse in 2014, the rest of us will have hopefully witnessed a dazzling spectacle from this icy Oort Cloud visitor, as we await the appearance of the next Great Comet.

Enjoy the show!

– Got question about Comet ISON? Lights in the Dark has answers!

– Be sure to post those amazing post-perihelion pics of Comet ISON on Universe Today’s Flickr page.

Guide to Safely Viewing Comet ISON on Perihelion Day, November 28

The day of truth is fast approaching. Will Comet ISON’s sungrazing ways spark it to brilliance or break it to bits? How bright will the comet become? Studying the latest images from NASA’s STEREO Ahead sun-watching spacecraft, it’s obvious that ISON remains healthy and intact. The most recent pictures taken from the ground confirm that no major breakup has occurred. Assuming that ISON doesn’t crumble apart on Nov. 28, when it passes just 730,000 miles (1.2 million km) from the sun, it could brighten to -4 magnitude or better in the hours leading up to and after the moment of perihelion at 12:24:57 p.m. CST (18:24:57 UT).

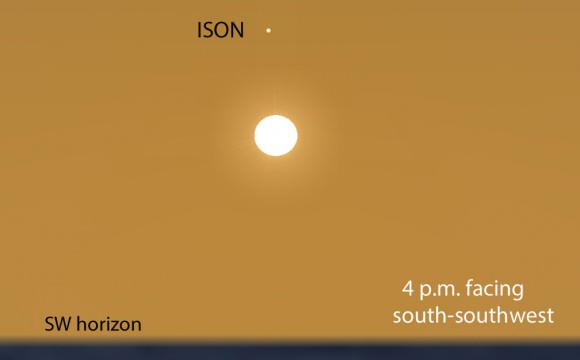

For comparison, the planet Venus hovers around -4 magnitude and is routinely visible visible with the naked eye in broad daylight if you know exactly where to look. For the sake of establishing a baseline, let’s imagine that ISON will match Venus in magnitude during its crack-the-whip fling around the sun. Naturally, this would put the comet within range of naked eye visibility smack in the middle of the day. Well, maybe. ISON presents us with a little problem. While it may grow bright enough to view in daylight, it will be very close to the sun on perihelion day. Not only will it be difficult to tease from the solar glare, but with the sun only a degree or two away, there’s a real danger you could damage your eyes if you stray too close.

During the early morning hours of the 28th, ISON will lie approximately 2.5 degrees from the sun’s limb or edge. At the time of perihelion that separation narrows to less than 1/2 degree or one solar diameter. This is likely when the comet will shine brightest, but with the sun so close, it will be next to impossible to spot it with naked eye or binoculars at that time. Matter of fact, don’t even try – it’s not worth the risk of damaging your retinas. An expert observer with a carefully-aimed telescope might pick it up, but must use extreme caution that sunlight not enter the field of view. Come sunset, the distance widens again to a somewhat more comfortable 2.5 degrees.

Once, when following Venus as a crescent through inferior conjunction, I dared track it within 2.5 degrees of the sun. THAT was almost too close for comfort. I had to avert my vision from a brilliant wedge of internally reflected sunlight along one side of the view and wear sunglasses to temper the brilliance of the “safe zone” where Venus appeared.. Red and polarizing filters can help reduce glare and increase contrast for near-sun viewing of comets and planets.

In mid-January 2007, Comet C/2006 P1 McNaught had a similar close brush with the sun and peaked around magnitude -5. For several days around perihelion on Jan. 12 it was plainly visible with the naked eye in broad daylight. I spotted it 5.6 degrees from the sun at magnitude -3.5 (twice as faint as Venus) at 10 a.m. on Jan. 13 and 5 degrees from the sun the following day when I estimated its magnitude at -4.5. While close, 5 degrees is a much more comfortable distance for comet and inner planet viewing.

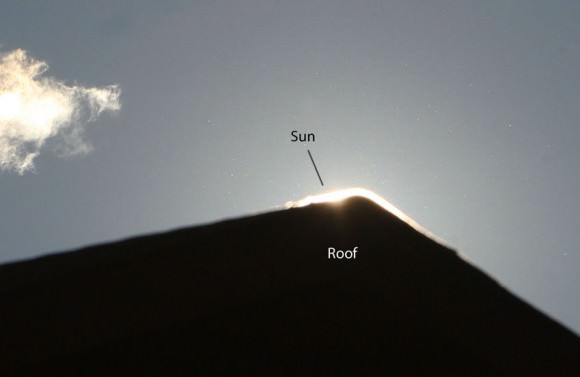

Whether naked eye, binocular or telescope, the favorite method for finding Comet McNaught in 2007 remains the best for Comet ISON in 2013. Block out the sun by placing something with a crisp edge in its way. Power poles, street lights (finally a good use for them), buildings, roof gables, church steeples and even clouds make ideal sun filters. They effectively remove the sun and allow you to look as close as is safe. Safety is critical here – never look directly at the sun. The damage to your retina will be swift and painless. No comet is worth losing your precious sense of sight.

As Earth rotates, the sun slowly moves across the sky. When using binoculars, if you start to see a bright reflection from approaching sunlight in the field of view, shift your position and re-cover the sun. I’ve been asked if you can simply hold an appropriate solar filter over your eye to dim the sun. Yes you can, but the filter will also completely block your view of the much, much fainter comet. Use the filter instead to dim the sun so you can hunt nearby for the comet.

Since ISON will be 2.5 degrees from the sun in the early morning and again just before sunset, those might be the best times to find it. Compared to the hour or two around perihelion, the glare will be less though ISON will likely be a little fainter. You can use the diagram above, suitable for mid-northern latitudes, to know in what direction from the sun to look for the comet. If ISON becomes at least as bright as Venus and your sky is deep blue and haze-free, you might just see it on Thursday before sitting down to that Thanksgiving turkey dinner. But of course much depends upon the comet.

Don’t fret if it’s cloudy. Head over to the Solar and Heliospheric (SOHO) website. There you’ll have a ringside seat Nov. 27-30 as Comet ISON makes its death-defying turn around the sun. Thereafter it will appear risk-free in the morning sky with what we hope will be a beautiful tail.

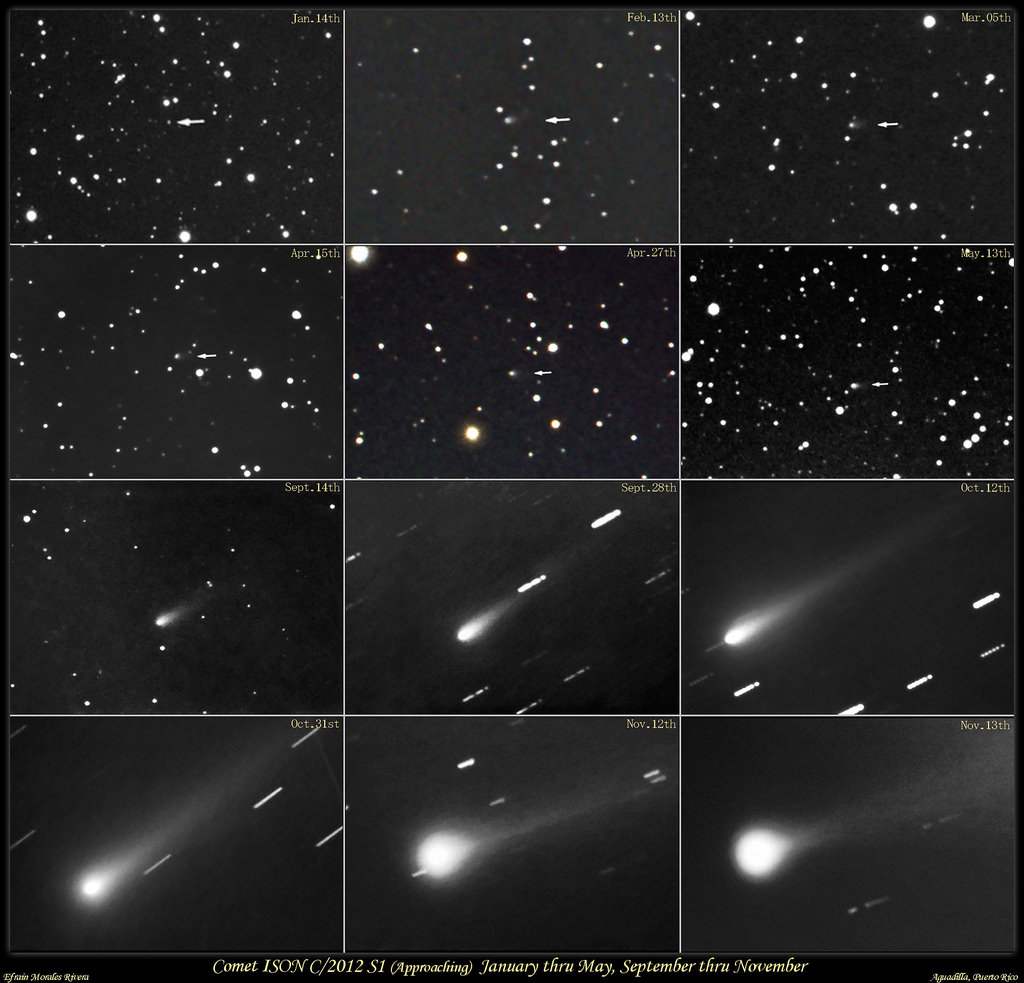

Say Goodbye to Comet ISON (for now): Timelapse and Image Gallery

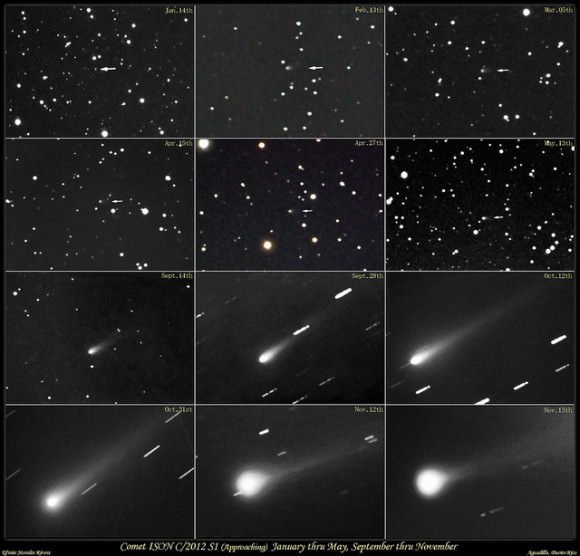

Comet ISON is heading towards its inexorable close pass of the Sun, which will occur on November 28, 2013. And while we’ve been enjoying great views from astrophotographers, that luxury is probably over as of today, as the comet is just getting to close to the Sun — and its blinding glare — for us to see it. But while we won’t be able to see it from Earth, we’re lucky to have a fleet of spacecraft that will be able to keep an eye on the comet for us! The STEREO spacecraft has already taken images of ISON hurtling towards the Sun; the Solar and Heliospheric Observatory (SOHO) will start observations on November 27. Then, the Solar Dynamics Observatory (SDO) will view the comet for a few hours during its closest approach to the Sun, and the X-Ray telescope on the Hinode spacecraft will view Comet ISON for about 55 minutes during perihelion.

Will Comet ISON survive its close pass and emerge brighter than ever? Only time will tell. You can keep track of what is going on with ISON here on Universe Today, as well as at NASA’s Comet ISON website, the Comet ISON Observing Campaign website, and there will be a special Hangout on Google+ during perihelion on Nov. 28.

Above is a gorgeous timelapse of ISON from the Teide observatory in the Canary Islands on Nov. 22nd, 2013. See more images and videos below.

Above is a screenshot from the live camera views from the Canada France Hawaii Telescope webcam. You can see a live view from their webcam any time at this link.

Want to get your astrophoto featured on Universe Today? Join our Flickr group or send us your images by email (this means you’re giving us permission to post them). Please explain what’s in the picture, when you took it, the equipment you used, etc.

Watch Live Webcast: Countdown to Comet ISON

We’re all watching what’s happening with Comet ISON, and today, November 21, 2013 Astronomy Magazine and Discover Magazine are hosting a “Countdown to Comet ISON” Google Hangout event, where the magazines’ expert editors will have all your comet questions answered. all the action starts at 20:00 UTC (3 pm EST). With ISON reaching its brightest this month, Astronomy Editor-in-Chief Dave Eicher, Discover Editor-at-Large Corey Powell and several others will discuss things like:

· When and where can you spot Comet ISON?

· How best to photograph the comet

· What scientists hope to learn from ISON

· Other amazing facts about comets across the ages

We’ll post the video feed here when it goes live, but can also watch (and RSVP) at the G+ event page.

If you miss it live, you can watch the replay above.

Get Out Your Comet Scorecards: Comet Nevski Now Visible With Binoculars

Is 2013 truly the “Year of the Comet?” Perhaps “Comets” might be a better term, as no less than five comets brighter than +10th magnitude grace the pre-dawn sky for northern hemisphere observers.

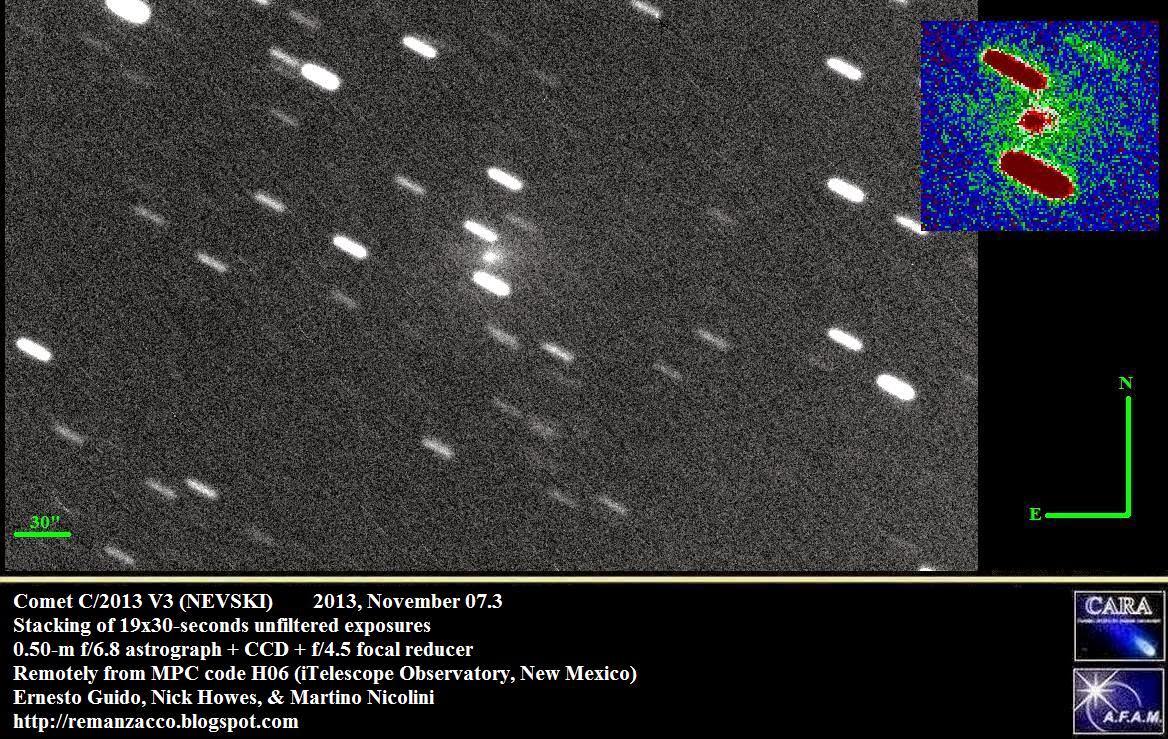

Comet C/2013 V3 Nevski has just brightened up 6 magnitudes — just over a 250-fold increase in brightness — and now sits at around magnitude +8.8. Comet Nevski was just recently discovered by Vitali Nevski using a 0.4 metre reflecting telescope 12 days ago on November 8th. If that name sounds familiar, it’s because Nevski discovered the comet from the Kislovodsk observatory located near Kislovodsk, Russia which is part of the International Scientific Optical Network survey which located comet ISON last year. In fact, there was some brief controversy early on in its discovery that Comet C/2012 S1 ISON should have had the moniker Comet Nevski-Novichonok.

At the time of discovery, Comet Nevski appeared to be nothing special: shining at magnitude +15.1, it was well below our +10 magnitude limit for consideration as “interesting,” and was projected to linger there for the duration of its passage through the inner solar system. About a dozen odd such comet discoveries crop up per year, most of which give astronomers a brief pause as the orbit and size of the comet become better known, only to discern that they’re most likely to be nothing extraordinary.

Such was to be the case with Comet Nevski, until it suddenly flared up this past weekend.

Observer Gianluca Masi caught Comet Nevski in outburst, using a Celestron C14 remotely as part of the Virtual Telescope 2.0 project:

You’ll note that Comet Nevski shows a small, spiky tail on the brief exposure. As of this writing, it currently sits at between magnitudes +8 and +9 and should remain there for the coming week if this current outburst holds.

Comet Nevski is well placed for northern hemisphere observers high in the morning sky, and will spend the remainder of November and early December crossing the astronomical constellation of Leo.

Here’s a blow-by-blow rundown on noteworthy events for this comet for the remainder of 2013:

November 23rd: Passes the +5.3 magnitude star Psi Leonis and crosses north of the ecliptic plane.

December 1st: Passes +3.4 magnitude star Eta Leonis.

December 6th: Passes +4.8 magnitude 40 Leonis and the bright +2nd magnitude star Algieba.

December 15th: Crosses into the constellation Leo Minor.

December 17th: Passes near the +5.5th magnitude star 40 Leonis Minoris.

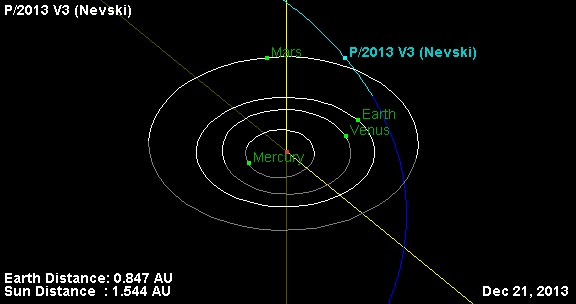

December 21st: Passes closest to Earth, at 0.847 Astronomical Units (A.U.s), or 126 million kilometres distant.

December 30th: Passes into the constellation Ursae Majoris.

Note that a “close pass” denotes a passage of the comet within a degree of a bright or interesting object.

The orbit of Comet Nevski is inclined 31.5 degrees relative to the ecliptic, and it will be headed for circumpolar for observers based in high northern latitudes as it dips back down below our “interesting” threshold of magnitude +10 in early 2014.

This comet passed perihelion on October 27th, 2013 just over a week prior to discovery. Comet Nevski is Halley-type comet, with a 27.5 year orbit.

So, looking at the “Comet Scorecard,” we currently have:

Comet C/2012 X1 LINEAR: Still undergoing a moderate outburst at magnitude +8.2, very low to the north east for northern hemisphere observers at dawn in the constellation Boötes.

Comet 2P/Encke: Reaches perihelion tomorrow at 0.33 AU’s from the Sun, shining at magnitude +7.7 near Mercury in the dawn sky but is now mostly lost in the Sun’s glare.

Comet C/2013 R1 Lovejoy: is currently well placed in the constellation Ursa Major crossing into Canes Venatici in the hours before dawn. Currently shining at magnitude +5.4, Comet R1 Lovejoy is visible to the unaided eye from a dark sky site. We caught sight of the comet last week with binoculars, looking like an unresolved globular cluster as it passed through the constellations of Leo and Leo Minor.

And of course, Comet C/2012 S1 ISON: As of this writing, ISON is performing up to expectations as it approaches Mercury low in the dawn shining at just above +4th magnitude. We’ve seen some stunning pictures as of late as ISON unfurls its tail, and now the eyes of the astronomical community will turn towards the main act: perihelion on November 28th. Will it fizzle or dazzle? More to come next week!

The recent outbursts of Comets X1 LINEAR and V3 Nevski are reminiscent of the major outburst of Comet Holmes back in 2007. Of course, the inevitable attempts to link these outbursts to the current sputtering solar max will ensue, but to our knowledge, no conclusive correlations exist. Remember, the outburst from Comet Holmes occurred as we were approaching what was to become a profound solar minimum.

Also, it might be tempting to imagine that all of these comets are somehow related, but they are in fact each on unique and very different orbits, and only appear in the rough general direction in the sky as seen from our Earthly vantage point… a boon for dawn patrol sky watchers!

Got pics? Send ‘em in to Universe Today!

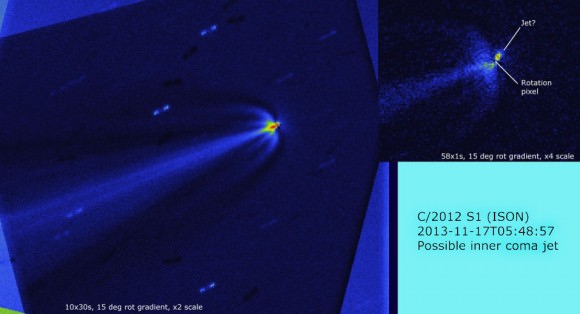

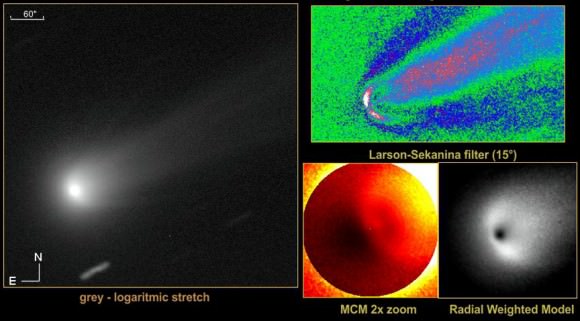

Comet ISON Grows Wings; Comet Lovejoy, a Fountain

Wonderful photos of Comets ISON and Lovejoy with their swollen comas and developing tails have appeared on these pages, but recently, amateur and professional astronomers have probed deeper to discover fascinating dust structures emanating from their very cores. Most comets possess a fuzzy, starlike pseudo-nucleus glowing near the center of the coma. Hidden within this minute luminous cocoon of haze and gas lies the true comet nucleus, a dark, icy body that typically spans from a few to 10 kilometers wide. Comet ISON’s nucleus could be as large as several kilometers and hefty enough (we hope!) to survive its close call with the sun on Nov. 28.

Last Wednesday morning Nov. 13 when calm air allowed a sharp view inside Comet Lovejoy’s large, 15-arc-minute-wide coma I noticed something odd about the false nucleus at low magnification, so I upped the power to 287x for a closer look. Extending from the fuzzy core in the sunward direction was a small cone or fountain-shaped structure of denser, brighter dust shaped like a miniature comet. It stretched eastward from the center and wrapped slightly to the south. Usually it’s harder than heck to see any details within the fuzzy, low-contrast environment of a comet’s coma unless that comet is close to Earth and actively spewing dust and ice. Lovejoy scored on both.

By good fortune, Dr. P. Clay Sherrod of the Arkansas Sky Observatories, USA, and Luc Arnold of Saint-Michel-l’Observatoire, France, shared images they’d made at high magnification of the identical feature right at the same time as my own observation. There’s no doubt that what we saw was a jet or combined jets of dust and vapor blasting from Lovejoy’s true nucleus. Jets are linear or fan-shaped features and carry ice, dust and even snowballs from inside the nucleus out into space. They typically form where freshly-exposed ice from breaks or fissures in the comet’s crust vaporizes in the sun’s heat.

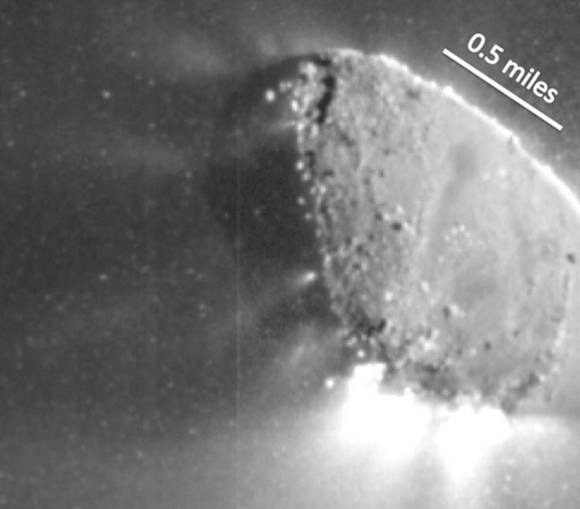

What I wouldn’t give to see one up close. Wait – we can. Take a look at the photo of Comet 103P/Hartley made during NASA’s EPOXI flyby mission in November 2010. Notice that most of Hartley’s crust appears intact with the jets being the main contributors to the dust and gas that form the coma and tail.

Spotting a jet usually requires good seeing (low atmospheric turbulence) and high magnification. They’re low-contrast features but worth searching for in any bright comet. Jets often point toward the sun for good reason – the sunward side of the comet is where the heating is happening. Activity dies back as the comet rotates to face away from the sun during the night and early morning hours. By studying the material streaming away from a comet via jets, astronomers can determine the rotation period of the nucleus.

Sometimes material sprayed by jets expands into a curved parabolic hood within the coma. This may explain the wing-shaped structures poking out from Comet ISON’s coma seen in recent photos. Possibly the Nov. 13-14 outburst released a great deal of fresh dust that’s now being pushed back toward the tail by the ever-increasing pressure of sunlight as the comet approaches perihelion.

The inner coma of Comet Hale-Bopp developed a striking series of hoods in March 1997 when a dust jet spewed material night after night from the comet’s rotating nucleus. The animation captures garden sprinkler effect beautifully. Since the nucleus spun around every 11 hours 46 minutes, multiple spiraling waves passed through the coma in the sunward direction. To the delight of amateur astronomers at the time, they were plainly visible through the telescope.

When examining a comet, I start at low magnification and note coma shape, compactness and color as well as tail form and length and details like the presence of streamers or knots. Then I crank up the power and carefully study the area around the nucleus. Surprises may await your careful gaze. If Comet ISON does break up, the first sign of it happening might be an elongation or stretching of the false nucleus. If it’s no longer a small, star-like disk or if you notice a fainter, second nucleus tailward of the main, the comet’s days may be numbered.

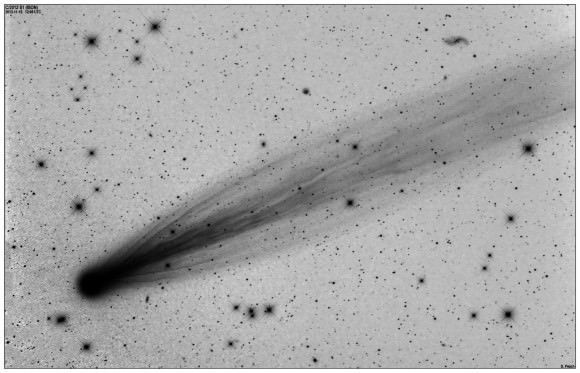

Whoa. Take a Look at Comet ISON Now

Let the show begin! With all our reports and images of Comet ISON being in outburst, this latest image from astrophotographer Damian Peach shows just how much activity is taking place in this comet as it races towards the Sun. “Hard to believe this is the same comet in my last image of Nov 10th!” Damian said via email.

ISON’s tail is suddenly full of streamers and features not seen before in this comet. At less than two weeks to its close encounter with the Sun on November 28, only a short amount of time will tell us if Comet ISON is just beginning to show off its brightness or if it is beginning to break apart.

The views here are through good quality telescopes. It is just now becoming visible to the naked eye, looking like a faint smudge at about magnitude +5.5.

Below is a “negative” view from Damain Peach, as well as a variety of views from Joseph Brimacombe and others that are coming in:

And an animation from Brimacombe:

Check out a simulator of how ISON will look in the skies from Earth or see this map of how to see ISON for yourself:

And for comparison, here is Damian Peach’s previous image from Nov. 10:

Weekly Space Hangout – November 15, 2013

Host: Fraser Cain

Guests: Jason Major & David Dickinson

Jason Major on:

Awesome New Image from Cassini

Mars Was Earthlike Millions of Years Ago

David Dickinson on:

Comet R1 LoveJoy at its brightest

Leonid Meteors this weekend

MAVEN Launches on Monday

Fraser Cain on:

Reminder re: Comet ISON photo contest

Cory Schmitz’ Aurora Photos

Curiosity’s Journey to Mount Sharpe

The Moon Has Bigger Craters on the Near Side

Super Typhoon Haiyan from Space

Two Workers Killed in Plesetsk

We record the Weekly Space Hangout every Friday at 12:00 pm Pacific / 3:00 pm Eastern. You can watch us live on Google+, Universe Today, or the Universe Today YouTube page.