Play the skywatching game long enough, and anything can happen.

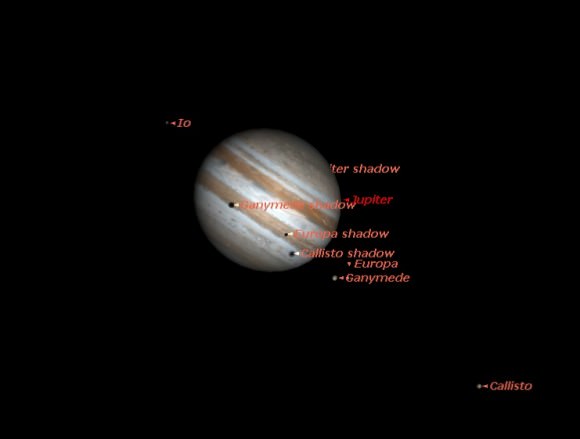

Well, nearly anything. One of the more unique clockwork events in our solar system occurs this weekend, when shadows cast by three of Jupiter’s moons can be seen transiting its lofty cloud tops… simultaneously.

How rare is such an event? Well, Jean Meeus calculates 31 triple events involving moons or their shadows occurring over the 60 year span from 1981 to 2040.

But not all are as favorably placed as this weekend’s event. First, Jupiter heads towards opposition just next month. And of the aforementioned 31 events, only 9 are triple shadow transits. Miss this weekend’s event, and you’ll have to wait until March 20th, 2032 for the next triple shadow transit to occur.

Of course, double shadow transits are much more common throughout the year, and we included some of the best for North America and Europe in 2015 in our 2015 roundup.

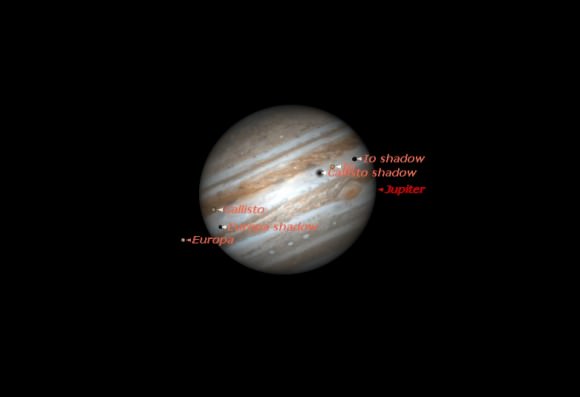

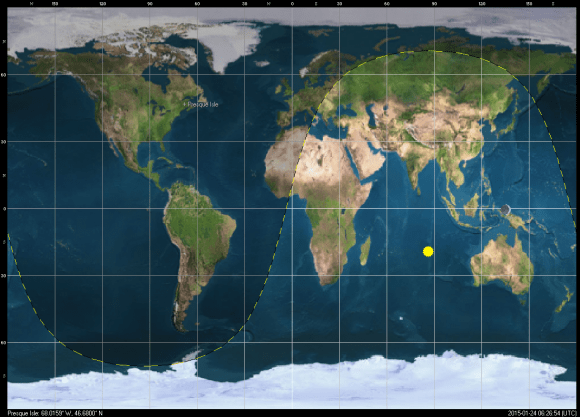

The key times when all three shadows can be seen crossing Jupiter’s 45” wide disk are on the morning of Saturday, January 24th starting at 6:26 Universal Time (UT) as Europa’s shadow ingresses into view, until 6:54 UT when Io’s shadow egresses out of sight. This converts to 1:26 AM EST to 1:54 AM EST. The span of ‘triplicate shadows’ only covers a period of slightly less than 30 minutes, but the action always unfolds fast in the Jovian system with the planet’s 10 hour rotation period.

Unfortunately, the Great Red Spot is predicted to be just out of view when the triple transit occurs, as it crosses Jupiter’s central meridian over three hours later at 10:28 UT.

The moons involved in this weekend’s event are Io, Callisto and Europa. Now, I know what you’re thinking. Seeing three shadows at once is pretty neat, but can you ever see four?

The short answer is no, and the reason has to do with orbital resonance.

The three innermost Galilean moons of Jupiter (Io, Europa and Ganymede) are locked in a 4:2:1 resonance. Unfortunately, this resonance assures that you’ll always see two of the innermost three crossing the disk of Jupiter, but never all three at once. Either Europa or Ganymede is nearly always the “odd moon out.”

To complete a ‘triple play,’ outermost Callisto must enter the picture. Trouble is, Callisto is the only Galilean moon that can ‘miss’ Jupiter’s disk from our line of sight. We’re lucky to be in an ongoing season of Callisto transits in 2015, a period that ends in July 2016.

Perhaps, on some far off day, a space tourism agency will offer tours to that imaginary vantage point on the surface of one of Jupiter’s moons such as Callisto to watch a triple transit occur from close up. Sign me up!

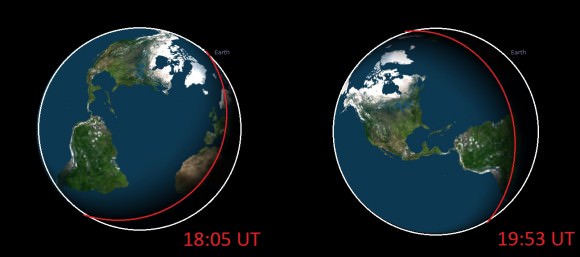

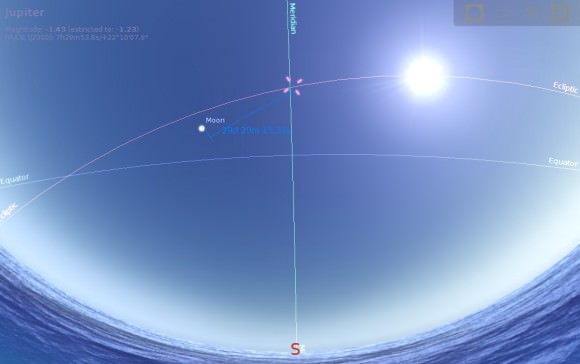

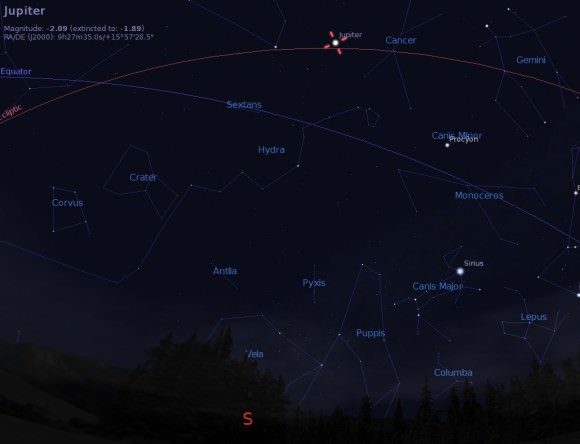

Jupiter currently rises in late January around 5:30 PM local, and sets after sunrise. It is also well placed for northern hemisphere observers in Leo at a declination 16 degrees north . This weekend’s event favors Europe towards local sunrise and ‘Jupiter-set,’ and finds the gas giant world well-placed high in the sky for all of North America in the early morning hours of the 24th.

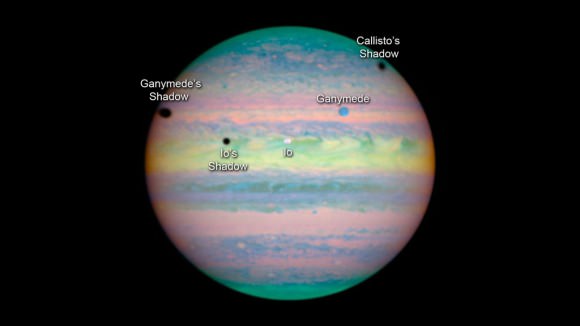

Look closely. Do the shadows of the individual moons appear different to you at the eyepiece? It’s interesting to note during a multiple transit that not all Jovian moon shadows are ‘created equal’. Distant Callisto casts a shadow that’s broad, with a ragged gray and diffuse rim, while the shadow of innermost Io appears as an inky black punch-hole dot. If you didn’t know better, you’d think those alien monoliths were busy consuming Jupiter in a scene straight out of the movie 2010. Try sketching multiple shadow transits and you’ll soon find that you can actually identify which moon is casting a shadow just from its appearance alone.

Other mysteries of the Galilean moons persist as well. Why did late 19th century observers describe them as egg-shaped? Can visual observers tease out such elusive phenomena as eruptions on Io by measuring its anomalous brightening? I still think it’s amazing that webcam imagers can now actually pry out surface detail from the Galilean moons!

Observing and imaging a shadow transit is easy using a homemade planetary webcam. We’d love to see someone produce a high quality animation of the upcoming triple shadow transit. I know that such high tech processing abilities — to include field de-rotation and convolution mapping of the Jovian sphere — are indeed out there… its breathtaking to imagine just how quickly the fledgling field of ad hoc planetary webcam imaging has changed in just 10 years.

The moons and Jupiter itself also cast shadows off to one side of the planet or the other depending on our current vantage point. We call the point when Jupiter sits 90 degrees east or west of the Sun quadrature, and the point when it rises and sets opposite to the Sun is known as opposition. Opposition for Jupiter is coming right up for 2015 on February 6th. During opposition, Jupiter and its moons cast their respective shadows nearly straight back.

Did you know: the speed of light was first deduced by Danish astronomer Ole Rømer in 1671 using the discrepancy he noted while predicting phenomena of the Galilean moons at quadrature versus opposition. There were also early ideas to use the positions of the Galilean moons to tell time at sea, but it turned out to be hard enough to see the moons and their shadows with a small telescope based on land, let alone from the pitching deck of a ship in the middle of the ocean.

And speaking of mutual events, we’re still in the midst of a season where it’s possible to see the moons of Jupiter eclipse and occult one another. Check out the USNO’s table for a complete list of events, coming to a sky near you.

And let’s not forget that NASA’s Juno spacecraft is headed towards Jupiter as well., Juno is set to enter a wide swooping orbit around the largest planet in the solar system in July 2016.

Now is a great time to get out and explore Jove… don’t miss this weekend’s triple shadow transit!

Read Dave Dickinson’s sci-fi tale of astronomical eclipse tourism through time and space titled Exeligmos.