The universe is stunning. Images from even the most modest telescopes can unveil its brilliant beauty. But couple that with a profound reason — our ability to question and understand the physical laws that dominate that brilliant beauty — and the image transforms into something much more spectacular.

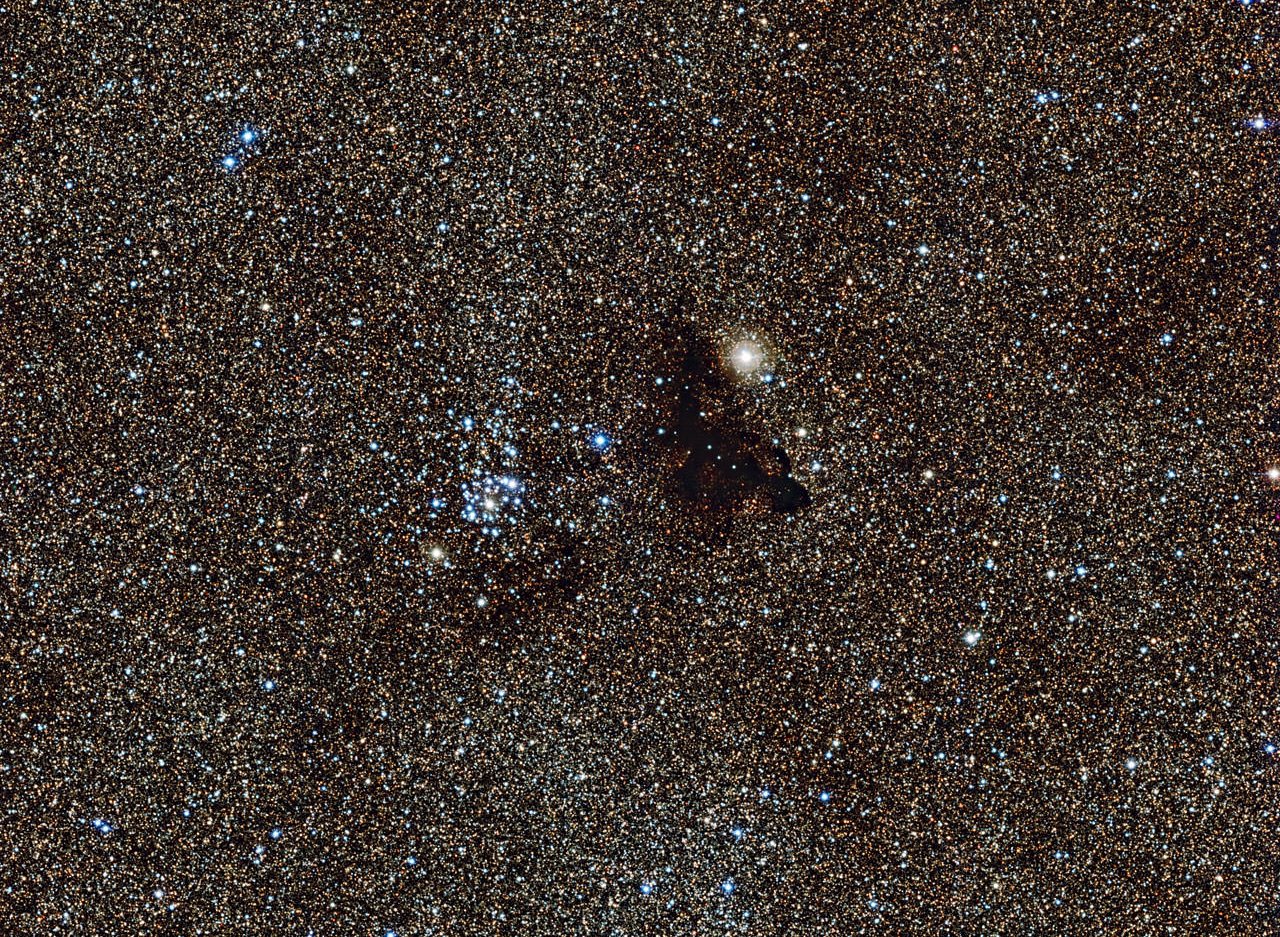

Take ESO’s latest image of two dramatic star formation regions in the southern Milky Way. John Herschel first observed the cluster on the left in 1834, during his three-year expedition to systematically survey the southern skies near Cape Town. He described it as a remarkable object and thought it might be a globular cluster. But future studies (and not to mention more dramatic images from larger telescopes) enriched our understanding, demonstrating that it was not an old globular but a young open cluster.

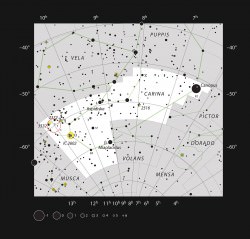

The Wide Field Imager at ESO’s La Silla Observatory in Chile recently captured the image again. The bright region on the left is the star cluster NGC 3603, located 20,000 light-years away in the Carina-Sagittarius spiral arm of the Milky Way galaxy. The bright region on the right is a collection of glowing gas clouds known as NGC 3576, located only 10,000 light-years away.

Stars are born in enormous clouds of gas and dust, largely hidden from view. But as small pockets in these clouds collapse under the pull of gravity, they become so hot they ignite nuclear fusion, and their light clears away — and brightens — the surrounding gas and dust.

Nearby regions of hydrogen gas are heated, and therefore partially ionized, by the ultraviolet radiation given off by the brilliant hot young stars. These regions, better known as HII regions, can measure several hundred light-years in diameter, and the one surrounding NGC 3603 has the distinction of being the most massive known in our galaxy.

Not only is NGC 3603 known for having the most massive HII region, it’s known for having the highest concentration of massive stars that have been discovered in our galaxy so far. At the center lies a Wolf-Rayet star system. These stars begin their lives at 20 times the mass of the Sun, but evolve quickly while shedding a considerable amount of their matter. Intense stellar winds blast the star’s surface into space at several million kilometers per hour.

Where NGC 3603 is notable for its extremes, NGC 3576 is notable for its extremities — the two huge curved objects in the outreaches of the cluster. Often described as the curled horns of a ram, these odd filaments are the result of stellar winds from the hot, young stars within the central regions of the nebula. The stars have blown the dust and gas outwards across a hundred light-years.

Additionally, the two dark silhouetted areas near the top of the nebula are known as Bok globules, dusty regions found near star formation sights. These dark clouds absorb nearby light and offer potential sites for the future formation of stars. They may further sculpt the dramatic landscape above, which is the smallest slice of our stunning universe