When Curiosity executed a perfect six-wheel landing on Mars on the morning of August 6 to the excitement of millions worldwide — not to mention quite a few engineers and scientists at JPL — it immediately began relaying images back to Earth. Although the initial views were low-resolution and taken through dusty lens covers, features of the local landscape around the rover could be discerned… distant hills, a pebbly surface, the rise of Gale Crater’s central peak — and a curious dark blur on the horizon that wasn’t visible in later images.

What could it have been? Another bit of lens dust? An image artifact? A piece of ancient Martian architecture that NASA demanded be erased from the image? As it turns out, it was most likely something even cooler (or at least real): the result of Curiosity’s descent stage crash-landing into the Martian surface.

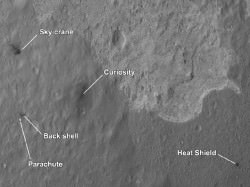

Seen in an image from NASA’s Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter’s HiRISE camera, the remnants of Curiosity’s descent to Mars are scattered around the landing site. The heat shield, parachute, back shell — and undeniably the star player of Curiosity’s EDL sequence, the descent stage and sky crane — all landed in relatively close proximity to where the rover touched down. As it turned out, Curiosity’s’s rear Hazcam happened to be aimed right where the sky crane landed after it severed Curiosity’s bridles and rocketed safely away — just as it had been shown in the landing animation.

Seen in an image from NASA’s Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter’s HiRISE camera, the remnants of Curiosity’s descent to Mars are scattered around the landing site. The heat shield, parachute, back shell — and undeniably the star player of Curiosity’s EDL sequence, the descent stage and sky crane — all landed in relatively close proximity to where the rover touched down. As it turned out, Curiosity’s’s rear Hazcam happened to be aimed right where the sky crane landed after it severed Curiosity’s bridles and rocketed safely away — just as it had been shown in the landing animation.

See an infographic on Curiosity’s EDL timeline here.

Seen in the first images captured by Curiosity’s rear Hazcams just minutes after touchdown — but not in higher-resolution images acquired later — the dark blur is now thought to be a plume of dust and soil kicked up by the sky crane’s impact.

“We know that the cloud was real because we saw it in both the left and right rear Hazcams, so it wasn’t just a smudge on the lens cover or anything like that… and then 45 minutes later it was gone,” said Steven Sell, Deputy Operations for Entry, Descent and Landing at JPL, during an interview with Universe Today on Friday.

“When we were putting together the sequence of images of what would happen after touchdown, we specifically put in the Hazcam shots as soon as we could on the off chance that we would see something,” Sell said. “It was just one of those things where we had some choices we could make, and we said if we put these really close to landing maybe we’ll actually see part of the descent stage.”

Although capturing the sky crane or other part of the descent stage on camera was an intriguing idea, it wasn’t any particular goal of the mission.

“We know that the cloud was real because we saw it in both the left and right rear Hazcams, so it wasn’t just a smudge on the lens cover or anything like that.”

– Steven Sell, Deputy Operations for Entry, Descent and Landing at JPL in Pasadena, CA

“We literally weren’t even thinking about it,” Sell said. “It’s a total bonus that we were able to capture that.”

Unfortunately, the plume only appears in the initial Hazcam shots, which were taken through lens covers coated with dust from landing. It wasn’t until nearly an hour later that the covers were removed and clearer images were captured, and by then the plume was gone. Plus the Hazcams themselves are low-resolution by design — they’re more for navigation than landscape photography.

“Those cameras are not intended for doing that kind of science, or even any science at all,” said Sell. “They’re strictly engineering cameras.”

It’s been said that the best camera is the one you have with you, and in this case Curiosity’s best camera happened to be aimed in the right place at the right time. Plus the sky crane just so happened to land in view of the cameras that got turned on first, which wasn’t a guarantee.

“The descent stage had two possible directions to go: it could have gone forward or backward,” Sell explained. “The way it decides which way to go is whichever direction would take it more north. We knew that the science target is toward the south — the scientists want to study the mountain — and so we didn’t want to throw the descent stage toward the mountain.

“The descent stage had two possible directions to go: it could have gone forward or backward,” Sell explained. “The way it decides which way to go is whichever direction would take it more north. We knew that the science target is toward the south — the scientists want to study the mountain — and so we didn’t want to throw the descent stage toward the mountain.

Read: Curiosity’s First 360-Degree Color Panorama

“The good news is that the forward Hazcams were at a lower temperature upon landing, we knew they were going to be colder,” Sell said. “The cameras have to reach a certain temperature before they can take a picture, so we knew the rear Hazcams were going to get the picture first, and so the fact that the thing flew to the rear was another coincidence.”

About the same mass as the rover itself, the sky crane weighed about 800 kg (1700 lbs) at the time of impact — including 100 kg of fuel — and hit going 100 mph. That’s going to kick up a good-sized plume (although exactly how large has yet to be determined.)

“It was one hell of an impact,” Sell said.

You can watch Steve Sell describe this and other data from the first few days of the MSL mission in the press conference held at JPL on Friday, August 10 below, and follow Sell on his Twitter feed here.

Images: NASA/JPL-Caltech. HiRISE image NASA/JPL/University of Arizona.