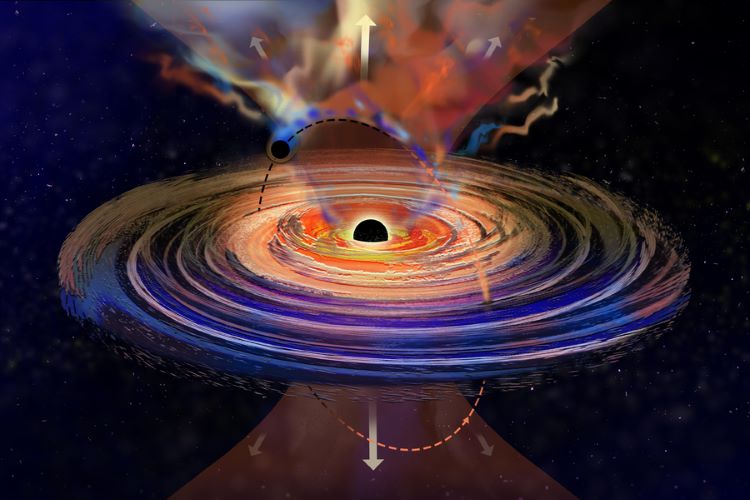

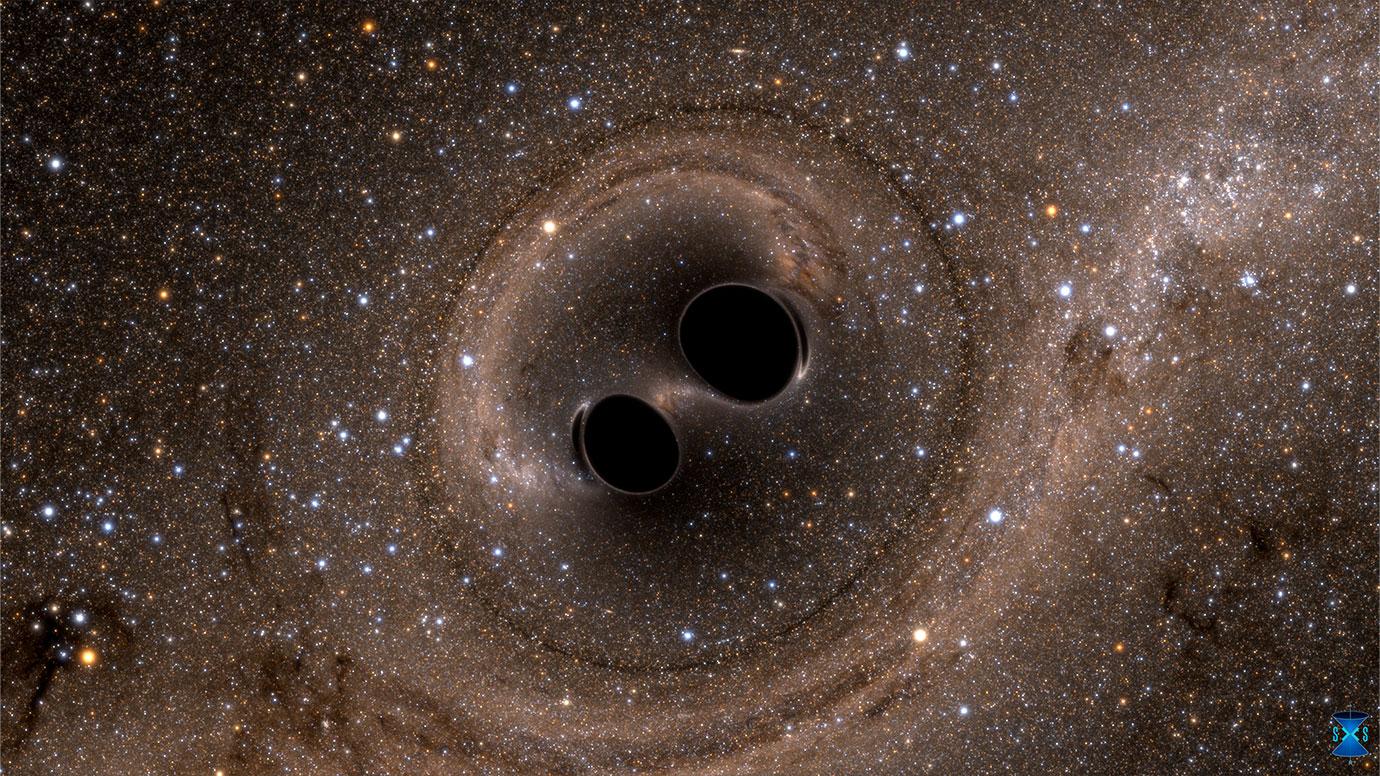

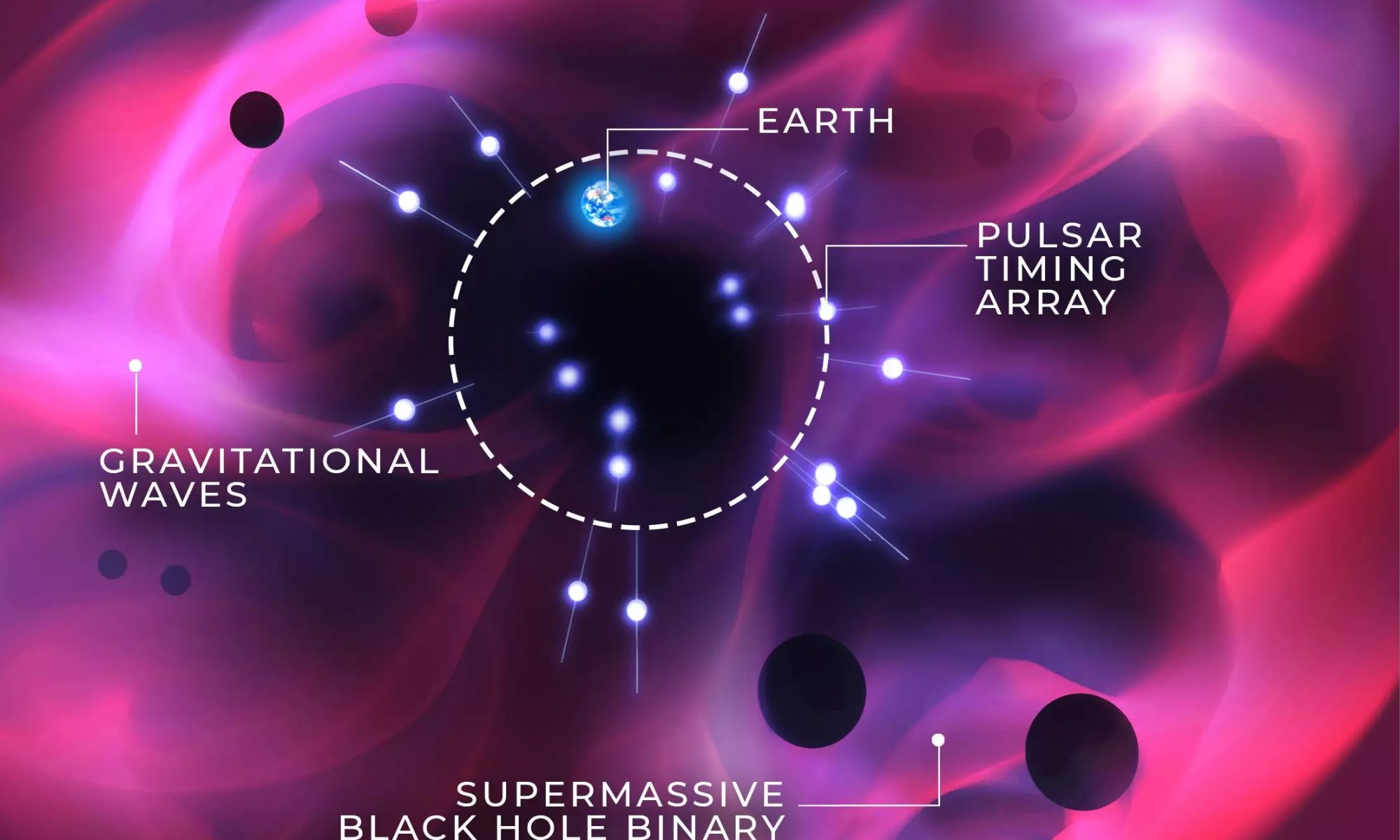

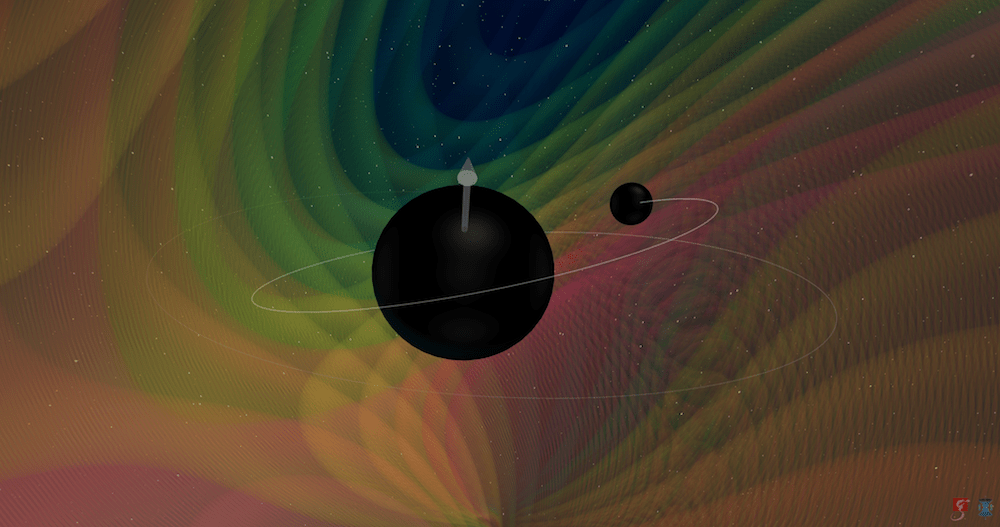

Can binary black holes, two black holes orbiting each other, influence their respective behaviors? This is what a recent study published in Science Advances hopes to address as a team of more than two dozen international researchers led by the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) investigated how a smaller black hole orbiting a supermassive black hole could alter the outbursts of the energy being emitted by the latter, essentially giving it “hiccups”. This study holds the potential to help astronomers better understand the behavior of binary black holes while producing new methods in finding more binary black holes throughout the cosmos.

Continue reading “A Supermassive Black Hole with a Case of the Hiccups”A Supermassive Black Hole with a Case of the Hiccups