[/caption]

Hubble is back! The wait is over and here are the new Hubble telescope images from the newly refurbished space telescope. Above is an image taken by the Wide Field Camera 3 (WFC3), a new camera aboard NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope, installed by NASA astronauts in May 2009, during the servicing mission to upgrade and repair the 19-year-old Hubble telescope. This is a planetary nebula, catalogued as NGC 6302, but more popularly called the Bug Nebula or the Butterfly Nebula.

NGC 6302 lies within our Milky Way galaxy, roughly 3,800 light-years away in the constellation Scorpius. The glowing gas is the star’s outer layers, expelled over about 2,200 years. The “butterfly” stretches for more than two light-years, which is about half the distance from the Sun to the nearest star, Alpha Centauri.

And there’s more!

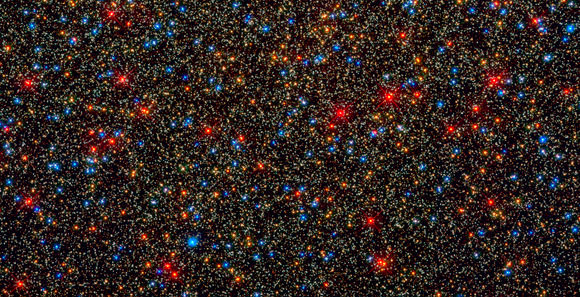

This one is absolutely awesome! This zoom into the globular star cluster Omega Centauri converges onto the Hubble Wide Field Camera 3’s panoramic view of 100,000 stars lying in the center of the cluster. The stars vary in age and change color as they get older. Most of them are middle-aged, yellowish stars like our Sun. But as they near the end of their lives, they balloon into red giants, and later still, into hot, blue stars.

This portrait of Stephan’s Quintet, also known as Hickson Compact Group 92, was taken by the new Wide Field Camera 3 (WFC3) aboard NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope. Stephan’s Quintet, as the name implies, is a group of five galaxies. The name, however, is a bit of a misnomer. Studies have shown that group member NGC 7320, at upper left, is actually a foreground galaxy about seven times closer to Earth than the rest of the group.

Three of the galaxies have distorted shapes, elongated spiral arms, and long, gaseous tidal tails containing myriad star clusters, proof of their close encounters. These interactions have sparked a frenzy of star birth in the central pair of galaxies. This drama is being played out against a rich backdrop of faraway galaxies.

The image, taken in visible and infrared light, showcases WFC3’s broad wavelength range.

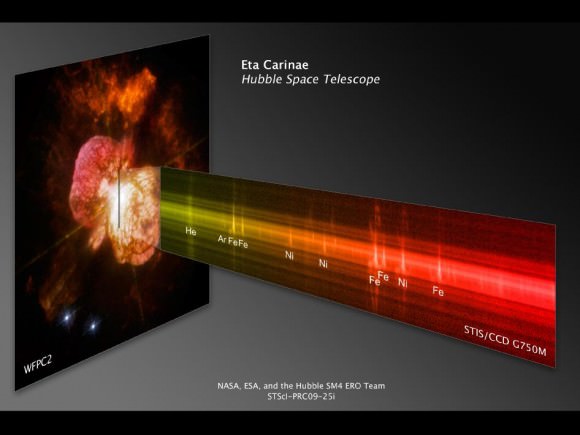

Observations by the newly repaired Space Telescope Imaging Spectrograph (STIS) on Hubble reveals the signature balloon-shaped clouds of gas blown from a pair of massive stars called Eta Carinae. This new observation shows some of the chemical elements that were ejected in the eruption seen in the middle of the 19th century.

STIS analyzed the chemical information along a narrow section of one of the giant lobes of gas. In the resulting spectrum, iron and nitrogen define the outer boundary of the massive wind, a stream of charged particles, from Eta Car A, the primary star. The amount of mass being carried away by the wind is the equivalent one sun every thousand years. While this “mass loss” may not sound very large, in fact it is an enormous rate among stars of all types. A very faint structure, seen in argon, is evidence of an interaction between winds from Eta Car A and those of Eta Car B, the hotter, less massive, secondary star.

Eta Car A is one of the most massive and most visible stars in the sky. Because of the star’s extremely high mass, it is unstable and uses its fuel very quickly, compared to other stars. Such massive stars also have a short lifetime, and we expect that Eta Carinae will explode within a million years.

This image of barred spiral galaxy NGC 6217 is the first image of a celestial object taken with the newly repaired Advanced Camera for Surveys (ACS) aboard the Hubble Space Telescope. The camera was restored to operation during the STS-125 servicing mission in May to upgrade Hubble. The barred spiral galaxy NGC 6217 was photographed on June 13 and July 8, 2009, as part of the initial testing and calibration of Hubble’s ACS. The galaxy lies 6 million light-years away in the north circumpolar constellation Ursa Major. The blue haze at the edges are baby stars being born.

About Hubble’s repair, NASA’s Ed Weiler said, “The astronauts basically did a total repair job on Hubble, and fixed two instruments that haven’t been working for a long time. It’s not an 19 year old telescope, it’s a new telescope again.”

NASA admisinatrator Charlie Bolden, who participated in an earlier Hubble repair mission, said at the press conference unveiling the new images that “after almost twenty years of service we are so proud and honored to part of the Hubble story. The telescope is now equipped to last well into the next decade. Hubble is one of the most accomplished scientific instruments ever, and it has captured the imagination of people everywhere.”

For the full gallery of new Hubble images, see this NASA webpage.

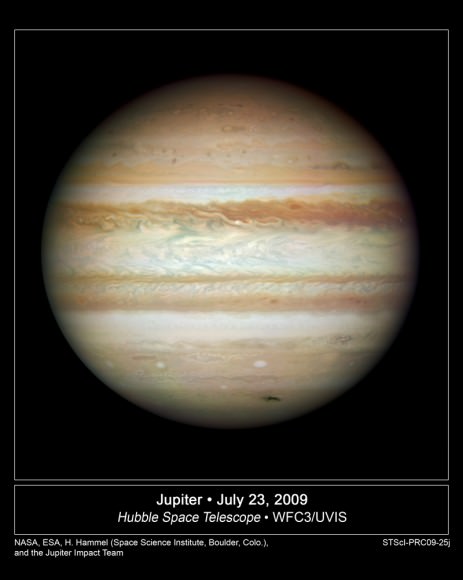

And here’s one more: a full view of Jupiter with the impact scar visible.

Sources: NASA, ESA