Freddie Mercury, the frontman from the rock band Queen, is getting his name etched in the night sky. No, they’re not naming another planet after him. That would be confusing. Instead, an asteroid will bear the name of the iconic singer.

If you don’t know much about the band Queen, there’s a connection between them and astronomy. Brian May, the band’s guitarist, holds a PhD. in astrophysics. He studied reflected light from interplanetary dust and the velocity of dust in the plane of the Solar System. But when Queen became mega-popular in the 70’s, he abandoned astrophysics, for the most part.

Brian May is still involved with space, and has an interest in asteroids. He helped the ESA launch Asteroid Day in June 2016, to raise awareness of the threat that asteroids pose to Earth. So there’s the connection.

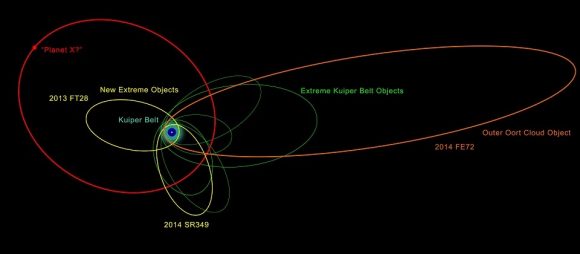

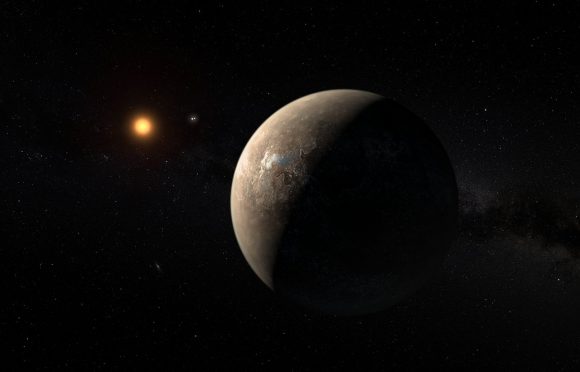

As for the asteroid that will bear Freddie Mercury’s name, it was previously named Asteroid 17473, but will now be known as Asteroid FreddieMercury 17473. It’s a rock about 3.5 km in diameter in the asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter.

Today would have been Freddie’s 70th birthday, if he were still alive. So this naming is a fitting commemorative gesture. According to the International Astronomical Union, who handles the naming of objects in space, the naming of the asteroid is in honour of “Freddie’s outstanding influence in the world.”

Brian May explains things in this video:

We’re mostly science-minded people, so you may be skeptical of Freddie’s influence in the world. He was no scientist, that’s for sure. But if you lived through Queen’s heyday, as I did, you can sort of see it.

Freddie Mercury was a very polished entertainer, with a great voice and fantastic stage presence. He mastered the theatrical side of performing as a rock frontman, and his voice spanned four octaves. The music he made with his band-members in Queen was very original. Mercury was a creative force, that’s for sure.

Check out “Killer Queen” from 1974.

Plus, William Shatner (aka Captain James Tiberius Kirk) clearly had a warm spot in his heart for Freddie and the rest of Queen. How else to explain his version of Queen’s timeless tune “Bohemian Rhapsody?”

If that isn’t a ringing endorsement of Freddie Mercury and Queen, I don’t know what is.

The asteroid that will bear Freddie Mercury’s name was discovered by Belgian astronomer Henri Debehogne in 1991. It travels an elliptical path around the Sun, and never comes closer than 350 million km to Earth. It isn’t very reflective, so only powerful telescopes can see it. But there it’ll be, for anyone with a powerful enough telescope to look with, as long as human civilization lasts.

Freddie Mercury isn’t the first entertainer to have something in space bear his name. In fact, he’s not even the first member of Queen to have that honor. An asteroid first seen in 1998 now bears the name Asteroid 52665 Brianmay, in honor of the guitarist from Queen.

Other musicians and singers who’ve had space rocks named after them include the Beatles, Enya, Frank Zappa, David Bowie, Aretha Franklin, Yes, and Bruce Springsteen. Authors Kurt Vonnegut, Vladimir Nabokov, and Douglas Adams and the characters Don Quixote, James Bond, Sherlock Holmes and Dr Watson also have the honor.

As for the rock itself, Oxford astrophysics professor Chris Lintott told the Guardian, “I think it’s wonderful to name an asteroid after Freddie Mercury. Pleasingly, it’s on a slightly eccentric orbit about the sun, just as the man himself was.”

Freddie died in 1991 from complications from AIDS, but his music still lives on. Maybe Asteroid FreddieMercury 17473 will help us remember him.

Sources: