[/caption]

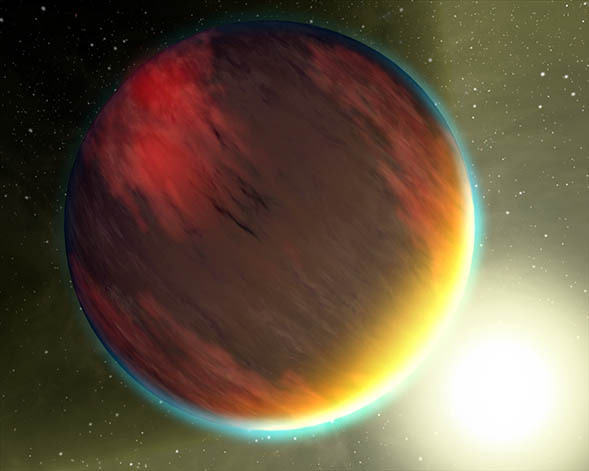

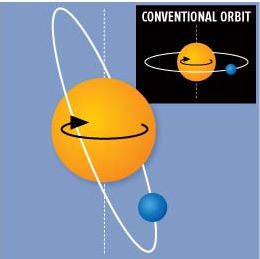

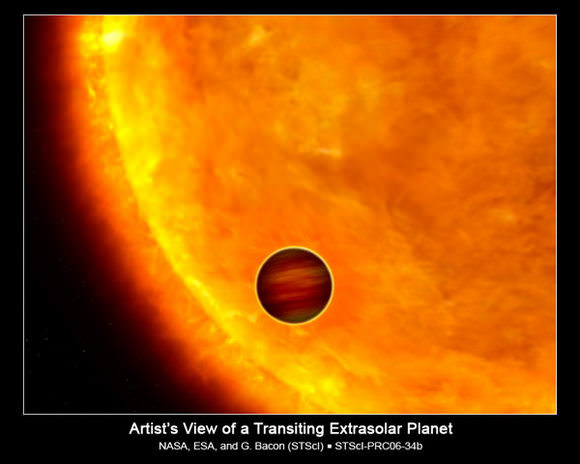

The basic chemistry for life has been detected the atmosphere of a second hot gas planet, HD 209458b. Data from the Hubble and Spitzer Space Telescopes provided spectral observations that revealed molecules of carbon dioxide, methane and water vapor in the planet’s atmosphere. The Jupiter-sized planet – which occupies a tight, 3.5-day orbit around a sun-like star — is not habitable but it has the same chemistry that, if found around a rocky planet in the future, could indicate the presence of life. Astronomers are excited about the detection, as it shows the potential of being able to characterize planets where life could exist.

HD 209458b is in the constellation Pegasus.

“It’s the second planet outside our solar system in which water, methane and carbon dioxide have been found, which are potentially important for biological processes in habitable planets,” said researcher Mark Swain of JPL. “Detecting organic compounds in two exoplanets now raises the possibility that it will become commonplace to find planets with molecules that may be tied to life.”

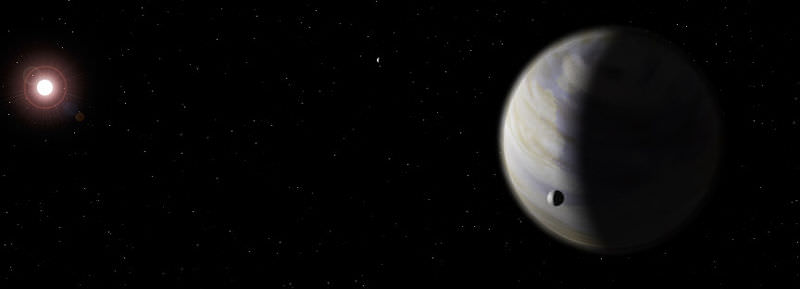

Over a year ago, astronomers detected these same organic molecules in the atmosphere of another hot, giant planet, called HD 189733b, using the same two space telescopes. Astronomers can now begin comparing the chemistry and dynamics of these two planets, and search for similar measurements of other candidate exoplanets.

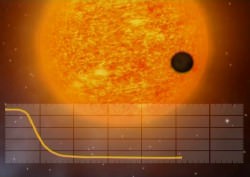

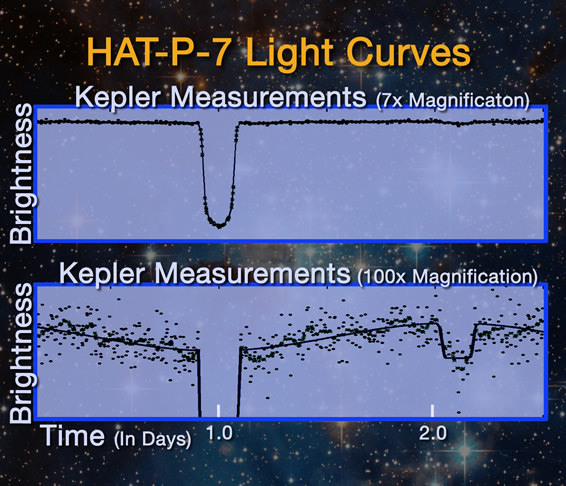

The detections were made through spectroscopy, which splits light into its components to reveal the distinctive spectral signatures of different chemicals. Data from Hubble’s near-infrared camera and multi-object spectrometer revealed the presence of the molecules, and data from Spitzer’s photometer and infrared spectrometer measured their amounts.

“This demonstrates that we can detect the molecules that matter for life processes,” said Swain. Astronomers can now begin comparing the two planetary atmospheres for differences and similarities. For example, the relative amounts of water and carbon dioxide in the two planets is similar, but HD 209458b shows a greater abundance of methane than HD 189733b. “The high methane abundance is telling us something,” said Swain. “It could mean there was something special about the formation of this planet.”

Rocky worlds are expected to be found by NASA’s Kepler mission, which launched earlier this year, but astronomers believe we are a decade or so away from being able to detect any chemical signs of life on such a body.

If and when such Earth-like planets are found in the future, “the detection of organic compounds will not necessarily mean there’s life on a planet, because there are other ways to generate such molecules,” Swain said. “If we detect organic chemicals on a rocky, Earth-like planet, we will want to understand enough about the planet to rule out non-life processes that could have led to those chemicals being there.”

“These objects are too far away to send probes to, so the only way we’re ever going to learn anything about them is to point telescopes at them. Spectroscopy provides a powerful tool to determine their chemistry and dynamics.”

For more information about exoplanets and NASA’s planet-finding program, check out PlanetQuest.

Source: Spitzer