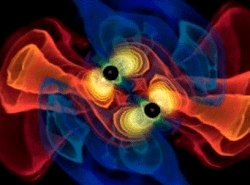

Frame from a simulation of the merger of two black holes and the resulting emission of gravitational radiation (NASA/C. Henze)

The short answer? You get one super-SUPERmassive black hole. The longer answer?

Well, watch the video below for an idea.

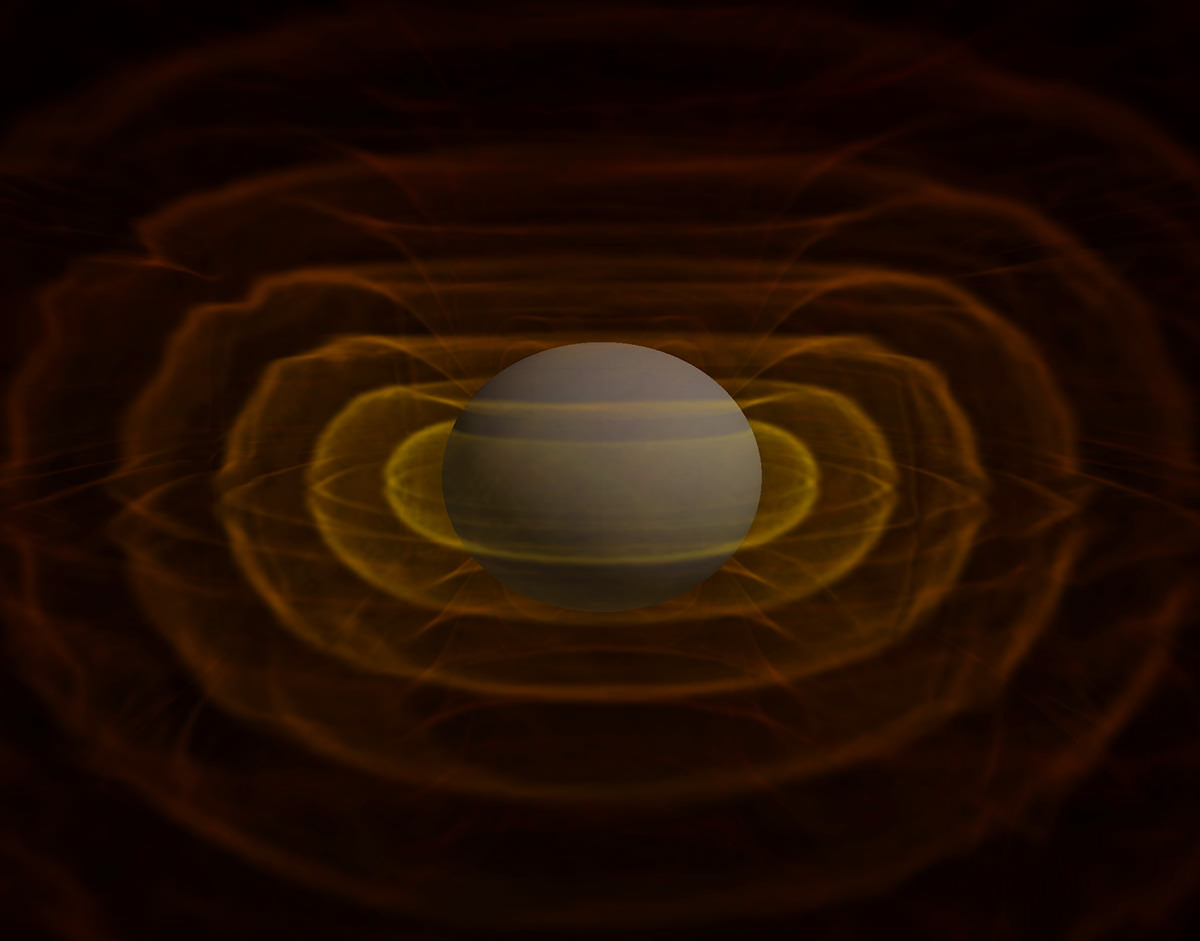

This animation, created with supercomputers at the University of Colorado, Boulder, show for the first time what happens to the magnetized gas clouds that surround supermassive black holes when two of them collide.

The simulation shows the magnetic fields intensifying as they contort and twist turbulently, at one point forming a towering vortex that extends high above the center of the accretion disk.

This funnel-like structure may be partly responsible for the jets that are sometimes seen erupting from actively feeding supermassive black holes.

The simulation was created to study what sort of “flash” might be made by the merging of such incredibly massive objects, so that astronomers hunting for evidence of gravitational waves — a phenomenon first proposed by Einstein in 1916 — will be able to better identify their potential source.

Read: Effects of Einstein’s Elusive Gravity Waves Observed

Gravitational waves are often described as “ripples” in the fabric of space-time, infinitesimal perturbations created by supermassive, rapidly rotating objects like orbiting black holes. Detecting them directly has proven to be a challenge but researchers expect that the technology will be available within several years’ time, and knowing how to spot colliding black holes will be the first step in identifying any gravitational waves that result from the impact.

In fact, it’s the gravitational waves that rob energy from the black holes’ orbits, causing them to spiral into each other in the first place.

“The black holes orbit each other and lose orbital energy by emitting strong gravitational waves, and this causes their orbits to shrink. The black holes spiral toward each other and eventually merge,” said astrophysicist John Baker, a research team member from NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center. “We need gravitational waves to confirm that a black hole merger has occurred, but if we can understand the electromagnetic signatures from mergers well enough, perhaps we can search for candidate events even before we have a space-based gravitational wave observatory.”

The video below shows the expanding gravitational wave structure that would be expected to result from such a merger:

If ground-based telescopes can pinpoint the radio and x-ray flash created by the mergers, future space telescopes — like ESA’s eLISA/NGO — can then be used to try and detect the waves.

Read more on the NASA Goddard new release here.

First animation credit: NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center/P. Cowperthwaite, Univ. of Maryland. Second animation: NASA/C. Henze.

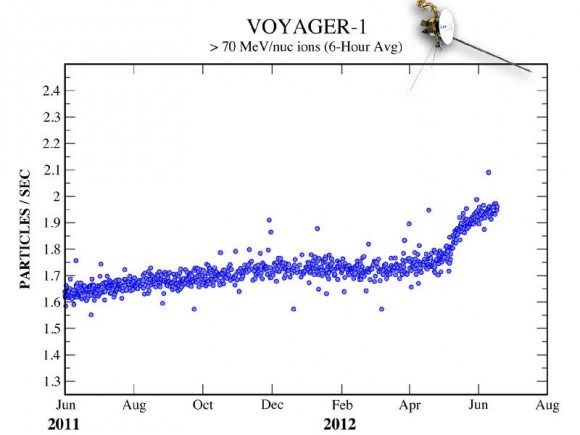

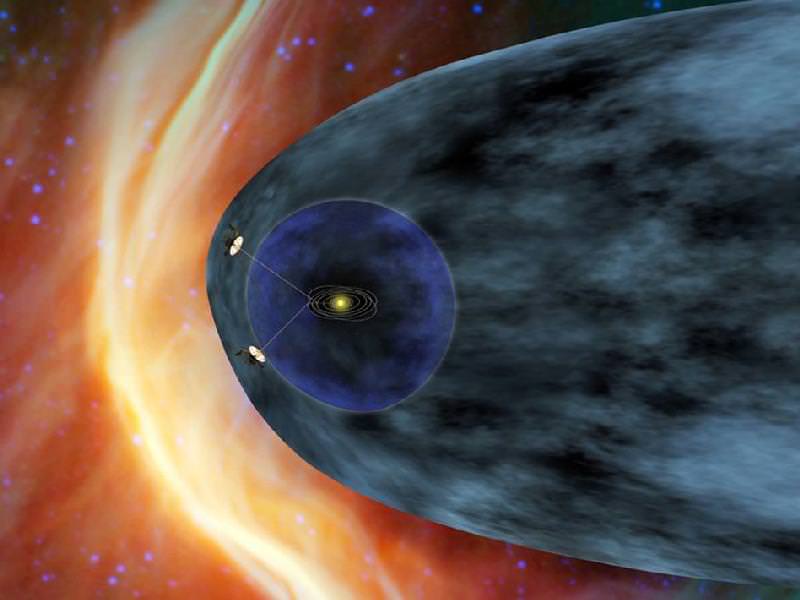

Data sent from Voyager 1 — a trip that currently takes the information nearly 17 hours to make — have shown steadily increasing levels of cosmic radiation as the spacecraft moves farther from the Sun. But on July 28, the levels of high-energy cosmic particles detected by Voyager jumped by 5 percent, with levels of lower-energy radiation from the Sun dropping by nearly half later the same day. Within three days both levels had returned to their previous states.

Data sent from Voyager 1 — a trip that currently takes the information nearly 17 hours to make — have shown steadily increasing levels of cosmic radiation as the spacecraft moves farther from the Sun. But on July 28, the levels of high-energy cosmic particles detected by Voyager jumped by 5 percent, with levels of lower-energy radiation from the Sun dropping by nearly half later the same day. Within three days both levels had returned to their previous states.