Watch live coverage of the EPOXI mission’s close flyby of Comet Hartley 2. Live coverage begins on November 4, 2010 at 9:30 a.m. EDT (6:30 a.m. PDT) from mission control at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory. You can watch NASA TV’s Media Channel online at this link, (and make sure you click on the “Media Channel” tab on the right side of the “tv” screen). You can also watch on JPL’s UStream channel online. Coverage includes closest approach, an educational segment, and the return of close-approach images. Emily Lakdawalla of the Planetary Society Blog has posted a very detailed timeline of the encounter.

Continue reading “Watch Live Coverage of EPOXI’s Hartley 2 Encounter on Nov. 4”

A Comet that Gives Twice?

[/caption]

While historically, meteor showers were portents of ill omens, we know today that they are the remnants of ejecta from comets entering our atmosphere. Many showers have had their parent comets identified. But a new study is suggesting that two meteor showers, the December Monocerotids and the November Orionids, may share the same parent.

The possibility of a single comet providing multiple showers isn’t too difficult to imagine. Since comets orbit the Sun in elliptical paths there are two potential points the path can intersect Earth’s orbit: Once on the way in and once on the way out. The trouble is that comets don’t tend to orbit directly in the ecliptic plane (defined by the plane on which the Earth orbits the Sun). Thus, comets only puncture through this plane at points known as “nodes”. As a body passes from the upper half to the lower (where upper and lower are the halves defined by Earth’s north and south poles respectively) this point of intersection of the orbit with the ecliptic plane is known as the descending node. When it heads back up, this is the ascending node. If both nodes happen to lie near enough to Earth’s orbital path, the potential for two meteor showers exists. Another possibility is that orbital evolution cause the nodes to change their position and, over time, crossed Earth’s orbit at two different points.

In principle, identifying a parent comet for two showers is much simpler with the first method. In that instance, the comet still orbits in the same path (or near enough) to be conclusively identified as the progenitor. If such an instance were to arise due to orbital evolution, the case must be much more indirect since interactions with planets, even at fairly large distances, can induce large uncertainties in the orbital history.

The December Monocerotids have been associated with a comet known as C/1917 F1 Mellish. Unfortunately for the researchers, the current orbital characteristics of the comet did not feature nodes in Earth’s orbit and did not match the November Orionids. Thus, to establish a connection between the two meteor streams, the team of astronomers from Comenius University in Slovakia, looked at the characteristics of the showers. In order to track these characteristics, the team utilized a publicly available database of meteor recordings from SonotaCo which uses webcams to capture video of meteors and then compute the orbital characteristics of the debris. However, the two showers did share suspiciously similar distributions of sizes (and thus brightnesses) of meteors as well as the velocity and less so, but still notable, the eccentricity.

This led the team to suspect that the node had evolved across Earth’s orbit sweeping by once in the past to create the stream of debris that forms the November shower, and more recently, crossed our orbit to create the December shower. If this hypothesis were correct, the team expected to also find subtle differences hinting that the November shower was older. Sure enough, the November Orionids show a larger dispersion of velocities than that of the December shower.

In the future, the team plans to revise the orbital characteristics of the parent comet. While they were able to show that the precession of the orbit would allow for the situation described, it was only one of a number of possible solutions. Thus, refining the knowledge of the orbit, perhaps from archival photographic plates, would allow the team to better constrain the path and determine the orbital history sufficiently to reinforce or refute their scenario.

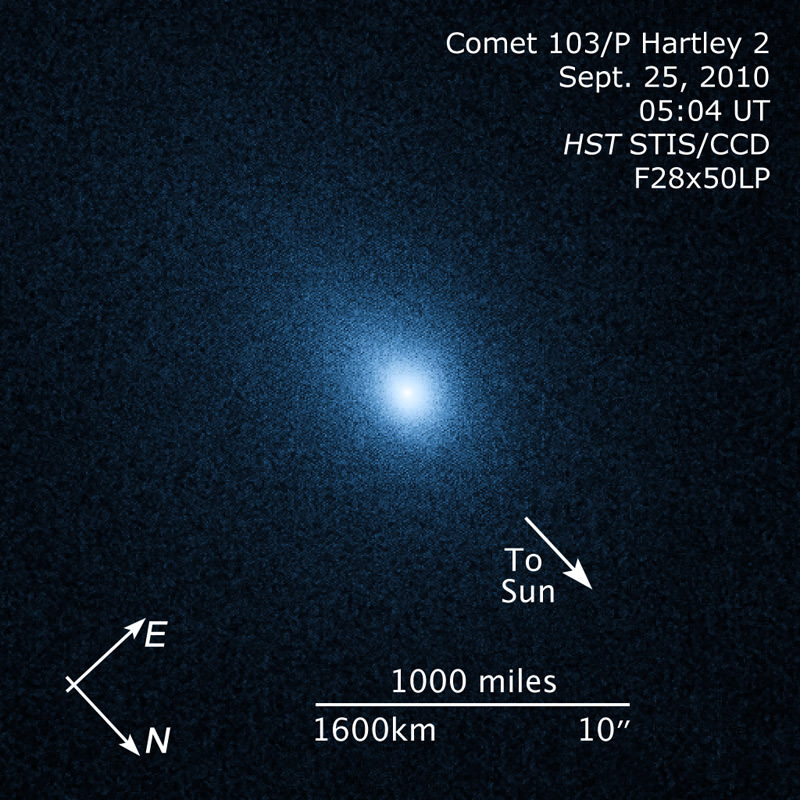

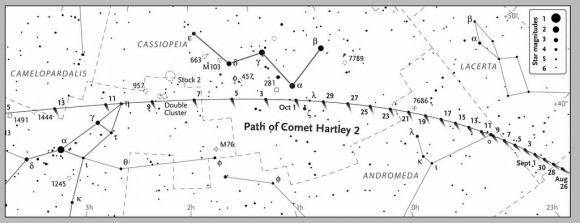

Comet Hartley 2 Scouted by WISE, Hubble for Upcoming Encounter

[/caption]

In a little less than a month, NASA’s Deep Impact spacecraft (its current mission is called EPOXI) will fly by the comet Hartley 2 to image the comet’s nucleus and take other measurements. In preparation for this event, both the Wide-field Infrared Survey Explorer (WISE) and the Hubble Space Telescope have imaged the comet, scouting out the destination for Deep Impact.

On November 4th of this year, Deep Impact will come within 435 miles (700 km) of the comet Hartley 2, close enough to take images of the comet’s nucleus.

The name of the mission is EPOXI, which is a combination of the names for the two separate missions the spacecraft has been most recently tasked with: the extrasolar planet observations, called Extrasolar Planet Observations and Characterization (EPOCh), and the flyby of comet Hartley 2, called the Deep Impact Extended Investigation (DIXI). The spacecraft itself is still referred to as Deep Impact, though, despite the changes and extensions of its mission.

NASA’s Deep Impact mission to slam a copper weight into comet Tempel 1 was a wonderful success, sending back data that greatly improved our understanding of the composition of comets. After the encounter, though, there was still a lot of life left in the spacecraft, so it was tasked with another cometary confrontation: take images of the comet Hartley 2.

Deep Impact is an example of NASA using a single spacecraft to perform multiple, disparate missions. In addition to impacting and imaging Tempel 1 and performing a flyby of Hartley 2, the spacecraft took observations of 5 different stars outside of our Solar System during the period between January and August of 2008 (8 were scheduled, but some observations were missed due to technical difficulties).

It looked at stars with known exoplanets to observe transits of those planets in front of the star, giving astronomers a better idea of the orbital period, albedo – or reflectivity – and size of the planets.

Click here for a list of the various stars and transits it observed, as listed on the mission page.

Deep Impact also took data on both the Earth and Mars as they passed in front of our own Sun, to help characterize what exoplanets with a similar size and composition the Earth and Mars would look like passing in front of a star.

As of September 29th, Deep Impact was about 23 million miles (37 million km) away from Hartley 2. It is approaching at roughly 607,000 miles a day (976,000 km), so that puts it at about 18 million miles (29 million km) away from the comet today. As it approaches, Deep Impact will speed up, to over 620,000 miles (1,000,000 km) per day.

You won’t have to depend on NASA’s observatories and the spacecraft to see a view of Hartley 2, though – you should be able to see it with the naked eye or binoculars near the constellation Perseus throughout the month of October. On October 20th, it will make its closest approach to Earth at a distance of 11 million miles (17.7 million km). The comet is officially designated 103P Hartley, and for viewing information you can go to Heavens Above.

As always, check this space regularly for updates on the upcoming flyby.

Sources: JPL here, here and here, Hubblesite, Heavens Above

Trojans May Yet Rain Down

It would be an interesting survey to catalog the initial reactions readers have to “Trojans”. Do you think first of wooden horses, or do asteroids spring to mind? Given the context of this website, I’d hope it’s the latter. If so, you’re thinking along the right lines. But how much do you really know about astronomical Trojans?

While most frequently used to discuss the set of objects in Jupiter’s orbital path that lie 60º ahead and behind the planet, orbiting the L4 and L5 Lagrange points, the term can be expanded to include any family of objects orbiting these points of relative stability around any other object. While Jupiter’s Trojan family is known to include over 3,000 objects, other solar system objects have been discovered with families of their own. Even one of Saturn’s moons, Tethys, has objects in its Lagrange points (although in this case, the objects are full moons in their own right: Calypso and Telesto).

In the past decade Neptunian Trojans have been discovered. By the end of this summer, six have been confirmed. Yet despite this small sample, these objects have some unexpected properties and may outnumber the number of asteroids in the main belt by an order of magnitude. However, they aren’t permanent and a paper published in the July issue of the International Journal of Astrobiology suggests that these reservoirs may produce many of the short period comets we see and “contribute a significant fraction of the impact hazard to the Earth.”

The origin of short period comets is an unusual one. While the sources of near Earth asteroids and long period comets have been well established, short period comets parent locations have been harder to pin down. Many have orbits with aphelions in the outer solar system, well past Neptune. This led to the independent prediction of a source of bodies in the far reaches by Edgeworth (1943) and Kuiper (1951). Yet others have aphelions well within the solar system. While some of this could be attributed to loss of energy from close passes to planets, it did not sufficiently account for the full number and astronomers began searching for other sources.

In 2006, J. Horner and N. Evans demonstrated the potential for objects from the outer solar system to be captured by the Jovian planets. In that paper, Horner and Evans considered the longevity of the stability of such captures for Jupiter Trojans. The two found that these objects were stable for billions of years but could eventually leak out. This would provide a storing of potential comets to help account for some of the oddities.

However, the Jupiter population is dynamically “cold” and does not contain a large distribution of velocities that would lead to more rapid shedding. Similarly, Saturn’s Trojan family was not found to be excited and was estimated to have a half life of ~2.5 billion years. One of the oddities of the Neptunian Trojans is that those few discovered thus far have tended to have high inclinations. This indicates that this family may be more dynamically excited, or “hotter” than that of other families, leading to a faster rate of shedding. Even with this realization, the full picture may not yet be clear given that searches for Trojans concentrate on the ecliptic and would likely miss additional members at higher inclinations, thus biasing surveys towards lower inclinations.

To assess the dangers of this excited population, Horner teamed with Patryk Lykawka to simulate the Neptunian Trojan system. From it, they estimated the family had a half life of ~550 million years. Objects leaving this population would then undergo several possible fates. In many cases, they resembled the Centaur class of objects with low eccentricities and with perihelion near Jupiter and aphelion near Neptune. Others picked up energy from other gas giants and were ejected from the solar system, and yet others became short period comets with aphelions near Jupiter.

Given the ability for this the Neptunian Trojans to eject members frequently, the two examined how many of the of short period comets we see may be from these reservoirs. Given the unknown nature of how large these stores are, the authors estimated that they could contribute as little as 3%. But if the populations are as large as some estimates have indicated, they would be sufficient to supply the entire collection of short period comets. Undoubtedly, the truth lies somewhere in between, but should it lie towards the upper end, the Neptunian Trojans could supply us with a new comet every 100 years on average.

Fully Functional Pan-STARRS is now Panning for Stars, Asteroids and Comets

[/caption]

There’s a new eye on the skies on the lookout for ‘killer’ asteroids and comets. The first Pan-STARRS (Panoramic Survey Telescope & Rapid Response System) telescope, PS1, is fully operational, ready to map large portions of the sky nightly. It will be sleuthing not just for potential incoming space rocks, but also supernovae and other variable objects.

“Pan-STARRS is an all-purpose machine,” said Harvard astronomer Edo Berger. “Having a dedicated telescope repeatedly surveying large areas opens up a lot of new opportunities.”

“PS1 has been taking science-quality data for six months, but now we are doing it dusk-to-dawn every night,” says Dr. Nick Kaiser, the principal investigator of the Pan-STARRS project.

Pan-STARRS will map one-sixth of the sky every month and basically be on the lookout for any objects that move over time. Frequent follow-up observations will allow astronomers to track those objects and calculate their orbits, identifying any potential threats to Earth. PS1 also will spot many small, faint bodies in the outer solar system that hid from previous surveys.

“PS1 will discover an unprecedented variety of Centaurs [minor planets between Jupiter and Neptune], trans-Neptunian objects, and comets. The system has the capability to detect planet-size bodies on the outer fringes of our solar system,” said Smithsonian astronomer Matthew Holman.

Pan-STARRS features the world’s largest digital camera — a 1,400-megapixel (1.4 gigapixel) monster. With it, astronomers can photograph an area of the sky as large as 36 full moons in a single exposure. In comparison, a picture from the Hubble Space Telescope’s WFC3 camera spans an area only one-hundredth the size of the full moon (albeit at very high resolution).

This sensitive digital camera was rated as one of the “20 marvels of modern engineering” by Gizmo Watch in 2008. Inventor Dr. John Tonry (IfA) said, “We played as close to the bleeding edge of technology as you can without getting cut!”

Each image, if printed out as a 300-dpi photograph, would cover half a basketball court, and PS1 takes an image every 30 seconds. The amount of data PS1 produces every night would fill 1,000 DVDs.

“As soon as Pan-STARRS turned on, we felt like we were drinking from a fire hose!” said Berger. He added that they are finding several hundred transient objects a month, which would have taken a couple of years with previous facilities.

Located atop the dormant volcano Haleakala (that’s Holy Haleakala to you, Bad Astronomer) Pan-STARRS exploits the unique combination of superb observing sites and technical and scientific expertise available in Hawaii.

Source: CfA

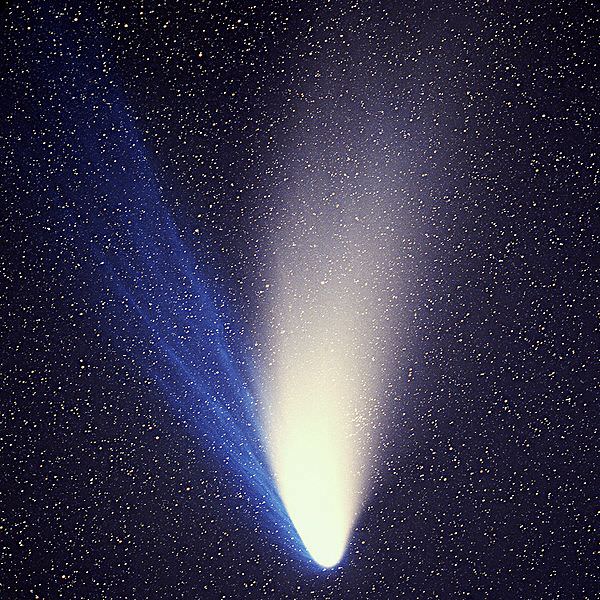

Many Famous Comets May be Visitors from Other Solar Systems

[/caption]

Most comets are thought to have originated great distances away, traveling to the inner solar system from the Oort Cloud. But new computer simulations show that many comets – including some famous ones – came from even farther: they may have been born in other solar systems. Many of the most well known comets, including the Hale Bopp Comet (above), Halley, and, most recently, McNaught, may have formed around other stars and then were gravitationally captured by our Sun when it was still in its birth cluster. This new finding solves the mystery of how the Oort cloud formed and why it is so heavily populated with comets.

Comets are believed to be leftovers from the formation of the solar system. They are observed to come to the solar system from all directions, so astronomers have thought the comet’s origin was from the Oort Cloud, a giant sphere surrounding the solar system. Some comets travel over 100,000 AU, in a huge orbit around the sun.

But comets may have formed around other stars in the cluster where the sun was born and been captured gravitationally by our sun.

Dr. Hal Levison from the Southwest Research Insitutue, along with Dr. Martin Duncan from Queen’s University, Kingston, Canada, Dr. Ramon Brasser, Observatoire de la Côte d’Azur, France and Dr. David Kaufmann (SwRI) used computer simulations to show that the Sun may have captured small icy bodies from its sibling stars while still in its star-forming nursery cluster.

The researchers investigated what fraction of comets might be able to travel from the outer reaches of one star to the outer reaches of another. The simulations imply that a substantial number of comets can be captured through this mechanism, and that a large number of Oort cloud comets come from other stars. The results may explain why the number of comets in the Oort cloud is larger than models predict.

While the Sun currently has no companion stars, it is believed to have formed in a cluster containing hundreds of closely packed stars that were embedded in a dense cloud of gas. During this time, each star formed a large number of small icy bodies (comets) in a disk from which planets formed. Most of these comets were gravitationally slung out of these prenatal planetary systems by the newly forming giant planets, becoming tiny, free-floating members of the cluster.

The Sun’s cluster came to a violent end, however, when its gas was blown out by the hottest young stars. These new models show that the Sun then gravitationally captured a large cloud of comets as the cluster dispersed.

“When it was young, the Sun shared a lot of spit with its siblings, and we can see that stuff today,” said Levison.

“The process of capture is surprisingly efficient and leads to the exciting possibility that the cloud contains a potpourri that samples material from a large number of stellar siblings of the Sun,” said co-author Duncan.

Evidence for the team’s scenario comes from the roughly spherical cloud of comets, known as the Oort cloud, that surrounds the Sun, extending halfway to the nearest star. It has been commonly assumed this cloud formed from the Sun’s proto-planetary disk. However, because detailed models show that comets from the solar system produce a much more anemic cloud than observed, another source is required.

“If we assume that the Sun’s observed proto-planetary disk can be used to estimate the indigenous population of the Oort cloud, we can conclude that more than 90 percent of the observed Oort cloud comets have an extra-solar origin,” Levison said.

“The formation of the Oort cloud has been a mystery for over 60 years and our work likely solves this long-standing problem,” said Brasser.

“Capture of the Sun’s Oort Cloud from Stars in its Birth Cluster,” was published in the June 10 issue of Science Express.

Source: Southwest Research Institute

A New Comet McNaught Could Be Seen with Naked Eye

[/caption]

A new comet with the familiar name of McNaught has just begun to grace the morning skies in the Northern Hemisphere, and it may provide observers a chance to see a naked-eye comet with a distinct tail. First images of McNaught C/2009 R1 show the tail shooting straight up into the sky, and this image was taken by amateur astronomer John Chumack from Ohio, who captured the comet passing by galaxy NGC 891 just before sunrise on June 8th. “I used a 5.5 inch telescope and a Canon Rebel Xsi digital camera to take this 15 minute exposure,” Chumack said. “It also looked great through binoculars.”

This is the latest comet discovered by Australian astronomer Robert H. McNaught, who spotted this new comet on September 9, 2009. One of the brightest comets of the past decade also bore McNaught’s name, Comet McNaught, (C/2006 P1).

The new Comet McNaught can be found low in the northeastern sky before dawn, now moving through the constellation Perseus. This coming weekend of Friday, June 11, through Sunday, June 13 should be a good time to look for the comet, as we have a New Moon on the 12th.

However, it will be brighter later next week, as it approaches Earth for a 1.13 AU close encounter on June 15th and 16th. Right now, the comet is right at the threshold of naked eye visibility (6th magnitude) and could become as bright as the stars of the Big Dipper before the end of the month.

Since this is the comet’s first visit to the inner solar system, it is uncertain how bright it will get, but skywatchers should definitely take advantage of this opportunity.

The comet’s atmosphere, or the gas expanding from the comet’s nucleus is actually really huge — estimated to be larger than the planet Jupiter, and that’s what makes this one a possible naked-eye object.

In addition to the sky maps at Astronomy Magazine, Heaven’s Above also has sighting times listed, Sky & Telescope has another sky map, NASA’s Solar System Dynamics page has a listing for C/2009 R1, and Cosmos4U has a list of images from the new comet.

Thanks again to John Chumack for sharing his image!

Sources: Astronomy Magazine, Spaceweather.com, John Chumack’s website, Galactic Images, The Miami Valley

Astronomical Society

Does McNaught Take Title for Biggest Comet Ever?

[/caption]

There are different ways to measure a comet. The Hale Bopp Comet, for example has a nucleus of more than 60 miles in diameter, which is thought to be the biggest ever encountered, so far. And Comet Hyakutake’s tail stretched out at a distance of more than 500 million km from the nucleus, the largest known. But now a group of scientists have identified a new category of measuring a comet’s size: the region of space disturbed by the comet’s presence. And for this class, first prize goes to Comet C/2006 P1 McNaught, which graced our skies in Janauary and February 2007. Of course, McNaught might win the prize for most picturesque comet, too, as this stunning image from Sebastian Deiries of ESO shows.

Dr. Geraint Jones of University College, London and his team used 2007 data from the now-inoperable Ulysses spacecraft, which was able to gauge the size of the region of space disturbed by the comet’s presence.

Ulysses encountered McNaught’s tail of ionized gas at a distance downstream of the comet’s nucleus more than 225 million kilometers. This is far beyond the spectacular dust tail that was visible from Earth in 2007.

“It was very difficult to observe Comet McNaught’s plasma tail remotely in comparison with the bright dust tail,” said Jones, “so we can’t really estimate how long it might be. What we can say is that Ulysses took just 2.5 days to traverse the shocked solar wind surrounding Comet Hyakutake, compared to an incredible 18 days in shocked wind surrounding Comet McNaught. This shows that the comet was not only spectacular from the ground; it was a truly immense obstacle to the solar wind.”

A comparison with crossing times for other comet encounters demonstrates the huge scale of Comet McNaught. The Giotto spacecraft’s encounter with Comet Grigg-Skjellerup in 1992 took less than an hour from one shock crossing to another; to cross the shocked region at Comet Halley took a few hours.

“The scale of an active comet depends on the level of outgassing rather than the size of the nucleus,” said Jones. “Comet nuclei aren’t necessarily active over their entire surfaces; what we can say is that McNaught’s level of gas production was clearly much higher than that of Hyakutake.”

Jones presented his findings at the RAS National Astronomy Meeting in Glasgow, Scotland.

Source: RAS NAM

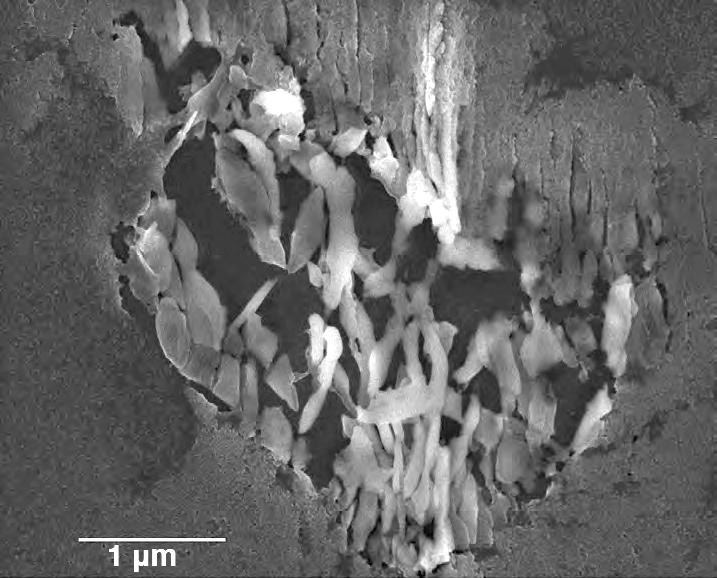

New Results from Stardust Mission Paint Chaotic Picture of Early Solar System

[/caption]

One of the most surprising results from the Stardust mission – which returned comet dust samples to Earth in 2006 – is that comets don’t just consist of particles from the icy parts of the outer solar system, which was the common assumption, but also includes sooty dust from the hot, inner region close to the Sun. A new study confirms this finding, and also provides the first chronological information from the Wild 2 comet (pronounced like Vilt 2). The find paints a chaotic picture of the early solar system.

Even some of the first looks at the cometary particles returned by Stardust showed that contrary to the popular scientific notion, there was enough mixing in the early solar system to transport material from the sun’s sizzling neighborhood and deposit it in icy deep-space comets. Whether the mixing occurred as a gentle eddy in a stream or more like an artillery blast is still unknown.

“Many people imagined that comets formed in total isolation from the rest of the solar system. We have shown that’s not true,” said Donald Brownlee back in 2006, principal investigator for Stardust.

The new study, conducted by scientists from Lawrence Livermore (Calif.) National Laboratory, shows the dust from comet 81P/Wild 2 has been altered by heating and other processes, which could have only occurred if a transport of space dust took place after the solar system formed some 4.57 billion years ago.

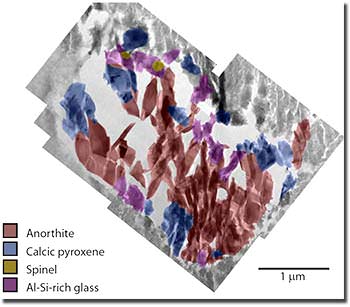

“The mission was expected to provide a unique window into the early solar system,” the team, led by Jennifer Matzel wrote in their paper, “by returning a mix of solar system condensates, amorphous grains from the interstellar medium, and true stardust – crystalline grains originating in distant stars. Initial results, however, indicate that comet Wild 2 instead contains an abundance of high-temperature silicate and oxide minerals analogous to minerals in carbonaceous chondrites.”

They analyzed a particle from the comet, about five micrometers across, known as Coki. The particle does not appear to contain any of the radiogenic isotope aluminum-26, which implies that this particle crystallized 1.7 million years after the formation of the oldest solar system solids. This means that material from the inner solar system must have traveled to the outer solar system, across a period of at least two million years.

“The inner solar system material in Wild 2 underscores the importance of radial transport of material over large distances in the early solar nebula,” said Matzel. “These findings also raise key questions regarding the timescale of the formation of comets and the relationship between Wild 2 and other primitive solar nebula objects.”

The presence of CAIs in comet Wild 2 indicates that the formation of the solar system included mixing over radial distances much greater than anyone expected.

Sources: LLNL, Astrobiology

WISE Spies Its First Comet

[/caption]

The Wide-field Infrared Survey Explorer or WISE is living up to expectations, as it now has discovered its first comet, shortly after finding its first asteroid. The spacecraft, just launched on Dec. 14, 2009 and first spotted the comet on January 22, 2010. WISE is expected to find millions of other objects during its ongoing survey of the whole sky in infrared light. Officially named “P/2010 B2 (WISE),” the comet is a dusty mass of ice more than 2 kilometers (1.2 miles) in diameter.

Comet and asteroid hunter Robert Holmes, who we have written about previously on Universe Today (whose Astronomical Research Observatory and Killer Asteroid Project in Illinois is not far from where I live) made the first ground-based confirmation of WISE’s comet discovery, with his home-built 0.81-meter telescope. Many large observatories attempted to confirm this discovery more than 7 days earlier including the Faulkes 2.0m telescope in Hawaii, without success. And due to poor weather, Holmes had to wait several days to get a look at the WISE comet himself. Holmes produces images for educational and public outreach programs like the International Astronomical Search Collaboration (IASC), which gives students and teachers the opportunity to make observations and discoveries, and a teacher actually assisted in the confirmation of this new comet.

Astronomers from the WISE team say the comet probably formed around the same time as our solar system, about 4.5 billion years ago. Comet WISE started out in the cold, dark reaches of our solar system, but after a long history of getting knocked around by the gravitational forces of Jupiter, it settled into an orbit much closer to the sun. Right now, the comet is heading away from the sun and is about 175 million kilometers (109 million miles) from Earth.

“Comets are ancient reservoirs of water. They are one of the few places besides Earth in the inner solar system where water is known to exist,” said Amy Mainzer of NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, Calif. Mainzer is the principal investigator of NEOWISE, a project to find and catalog new asteroids and comets spotted by WISE (the acronym combines WISE with NEO, the shorthand for near-Earth object).

“With WISE, we have a powerful tool to find new comets and learn more about the population as a whole,” said Mainzer. “Water is necessary for life as we know it, and comets can tell us more about how much there is in our solar system.”

“It is very unlikely that a comet will hit Earth,” said James Bauer, a scientist at JPL working on the WISE project, “But, in the rare chance that one did, it could be dangerous. The new discoveries from WISE will give us more precise statistics about the probability of such an event, and how powerful an impact it might yield.”

Comet WISE takes 4.7 years to circle the sun, with its farthest point being about 4 astronomical units away, and its closest point being 1.6 astronomical units (near the orbit of Mars). An astronomical unit is the distance between Earth and the sun. Heat from the sun causes gas and dust to blow off the comet, resulting in a dusty coma, or shell, and a tail.

Sources: JPL, Killer Asteroid Project