Are the ancient planets discovered around Kapteyn’s Star for real?

As the saying goes, all that glitters isn’t gold, and the same could be said in the fast-paced hunt for exoplanets. In 2014, we reported on an exciting new discovery of two new exoplanets orbiting Kapteyn’s Star. The news came out of the American Astronomical Society’s 224th Meeting held in Boston Massachusetts, and immediately grabbed our attention. The current number of exoplanet discoveries as of July 2015 sits at 1,932 and counting.

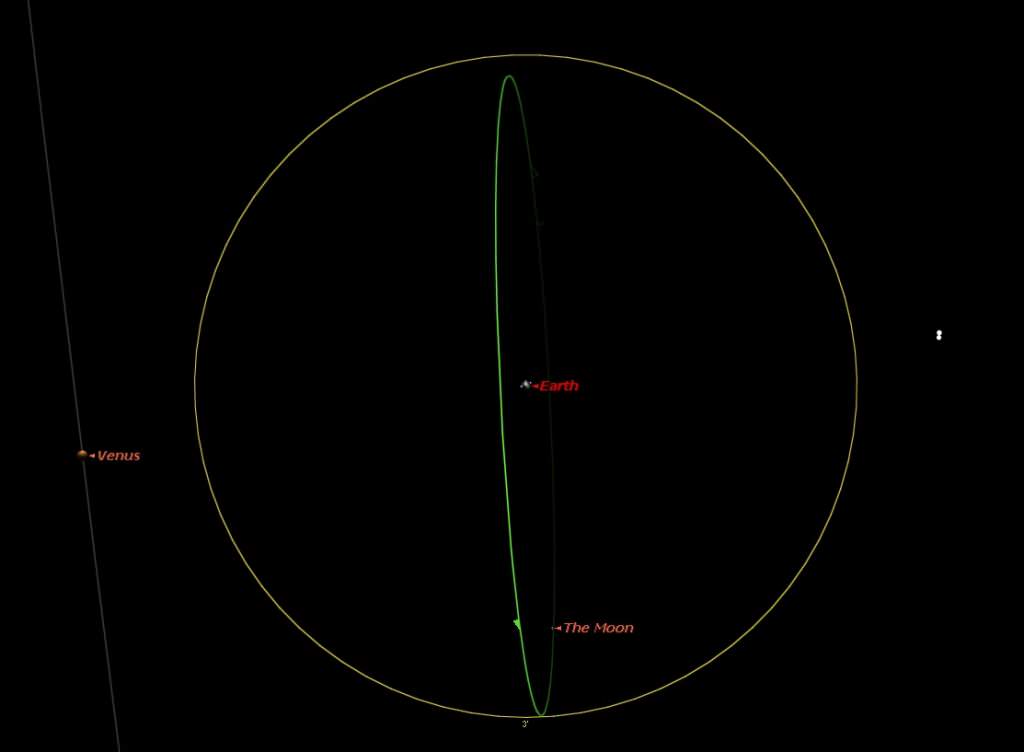

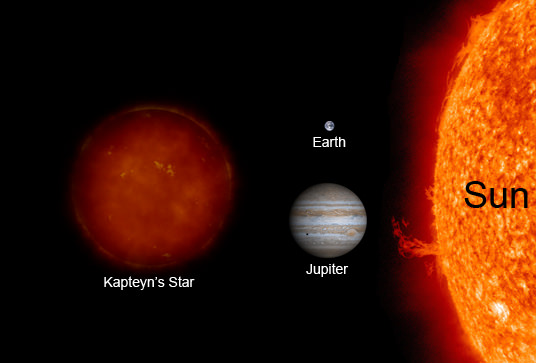

An M-class red dwarf, Kapteyn’s Star is relatively nearby at only 13 light years distant. The planetary discovery consisted of a world five times the mass of the Earth in a 48 day orbit (Kapteyn b), and a world seven times the mass of the Earth in a 122 day orbit (Kapteyn c). The discovery was hailed as an example of an ancient—possibly over 11 billion years old—system with its innermost world cast as a ‘super-Earth’ in the habitable zone…

But is Kapteyn-b not to be?

An interesting paper came up in the Astrophysical Journal Letters recently that suggests the exoplanets discovered orbiting Kapteyn’s Star in 2014 may in fact be spurious detections.

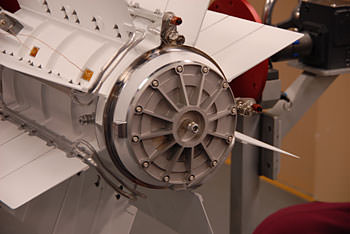

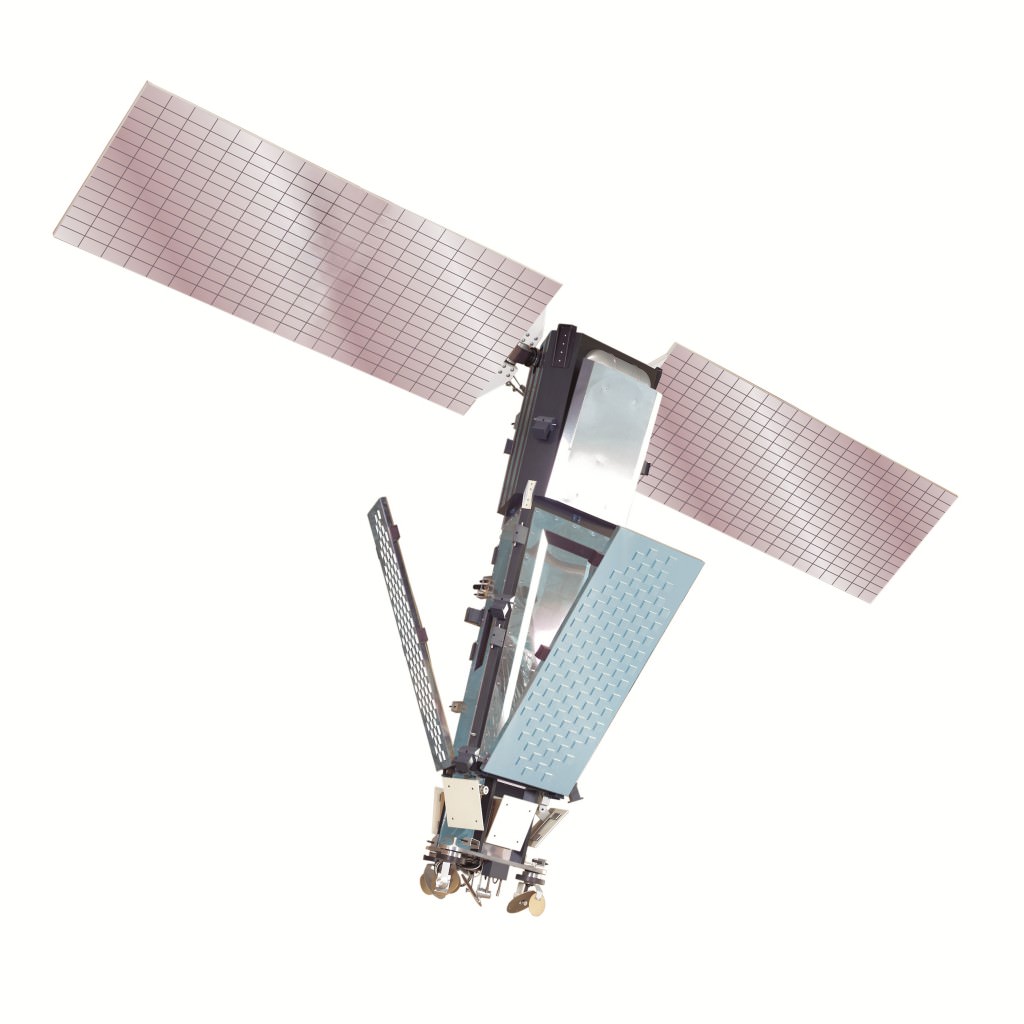

The idea of a planetary system around Kapteyn’s Star, real or not, is an interesting tale of exoplanet science. The original discovery was made using the High Accuracy Radial velocity Planetary research (HARP) instrument at the European Southern Observatory, with supporting observations from the Las Campanas and Keck Observatory. You’d think that would make the discoveries pretty air-tight. The planets discovered orbiting Kapteyn’s Star were discerned using the radial velocity method, looking at the spectra of the star for the characteristic tugging of an unseen companion.

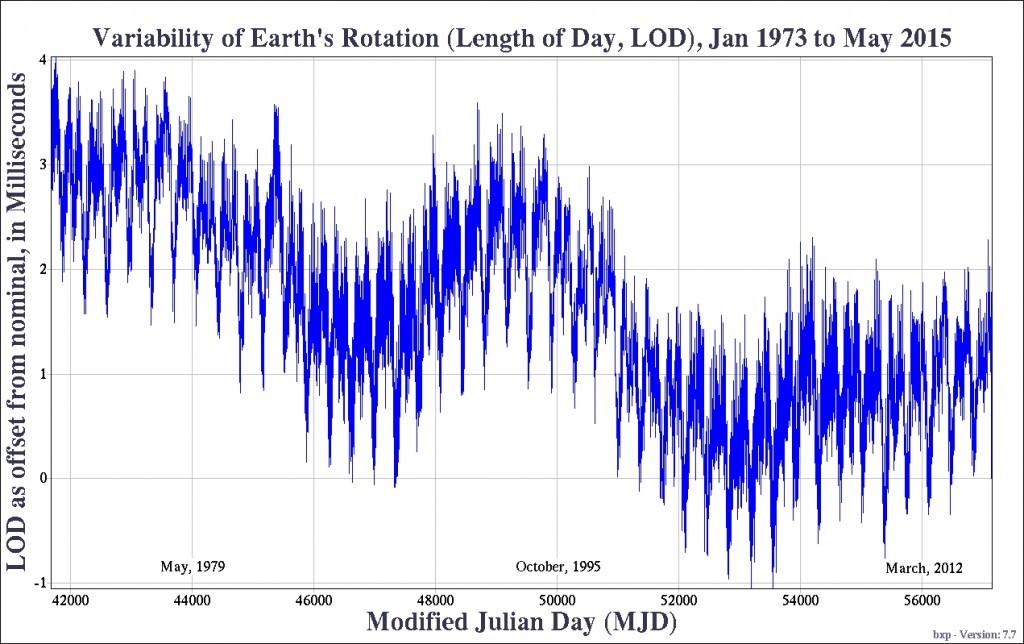

Recent research led by Paul Robertson of Pennsylvania State University suggests that the signal for the discovery of Kapteyn B may in fact be the result of stellar activity. Starspots—think sunspots on our own host star—can mimic the spectral signal of an unseen planet. Analyzing the HARPS data, we know that Kapteyn’s Star rotates once every 143 days. Kapteyn-b’s orbit of 48 days is very close to an integer fraction (143/48= 2.979) making it extremely suspicious.

Universe Today recently caught up with Paul Robertson, who had this to say about exoplanets around Kapteyn’s Star:

Q-How does this put the existence of a planet around Kapteyn’s Star in jeopardy?

“Based on our analysis of the star’s magnetic activity, we determined the star has a rotation period that is three times that of the orbital period for ‘planet b.’ Theoretical simulations have predicted—and subsequent observations have proven—that a star can create Doppler signals at integer fractions of its rotation period (that is, one half, one third, etc). Furthermore, the measurements of the star’s magnetic activity are correlated with the predicted Doppler shifts caused by planet b. In such cases, the simplest explanation for the observations is that the Doppler periodicity is caused by the star’s activity, rather than a planet whose signal coincidentally matches the star’s activity.”

Q-Is it possible to discern the starspot cycle that we’re seeing on Kapteyn’s Star?

“We infer the presence of active magnetic regions—possibly starspots—on the stellar surface through the variability of certain magnetically-sensitive absorption lines in the star’s spectrum. Previous observations suggest that the star’s brightness is relatively constant, so any starspots must be fairly small or not especially dark. It is possible that a space-based photometer such as K2 or TESS might see starspots.”

Q-Are future observations planned?

“Honestly, I don’t know. My paper used data from previous observing programs that are now available in public archives. I certainly think additional data would be quite valuable for Kapteyn’s Star. Given that Kapteyn’s Star is somewhat special, being the closest halo star and one of the oldest nearby stars, I suspect someone will take more observations.”

This discovery is significant either way. An ancient super-Earth orbiting in the habitable zone of a nearby star has had lots of time to get the engine of evolution underway, more than twice the span of the history of life on Earth. But if Kapteyn-b is merely a transitory flicker in the data, it also serves as a good case study in perils of exoplanet hunting as well.

There’s still a good deal of controversy, however, surrounding the existence of planets orbiting Kapteyn’s Star. One very recent paper released just last week on June 30th titled No Evidence for Activity Correlations in the Radial Velocities of Kapteyn’s Star is safely in the ‘pro- Kapteyn-b’ camp.

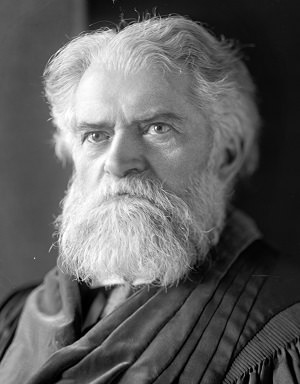

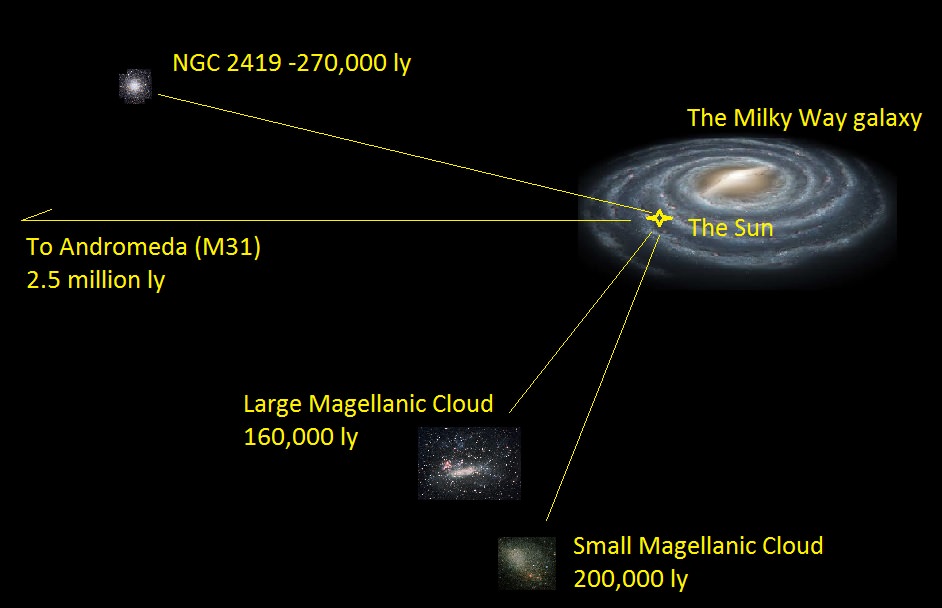

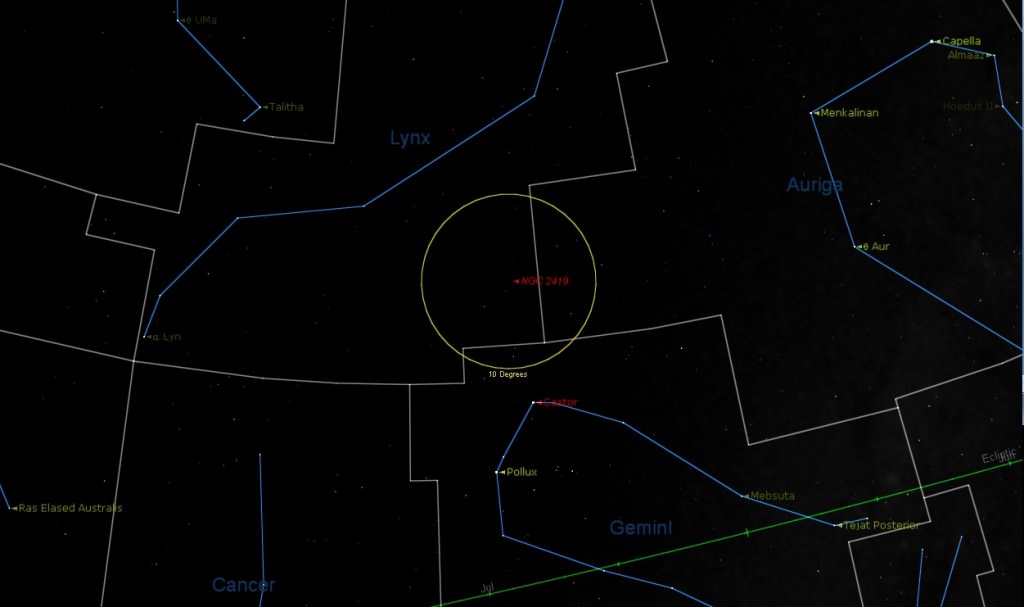

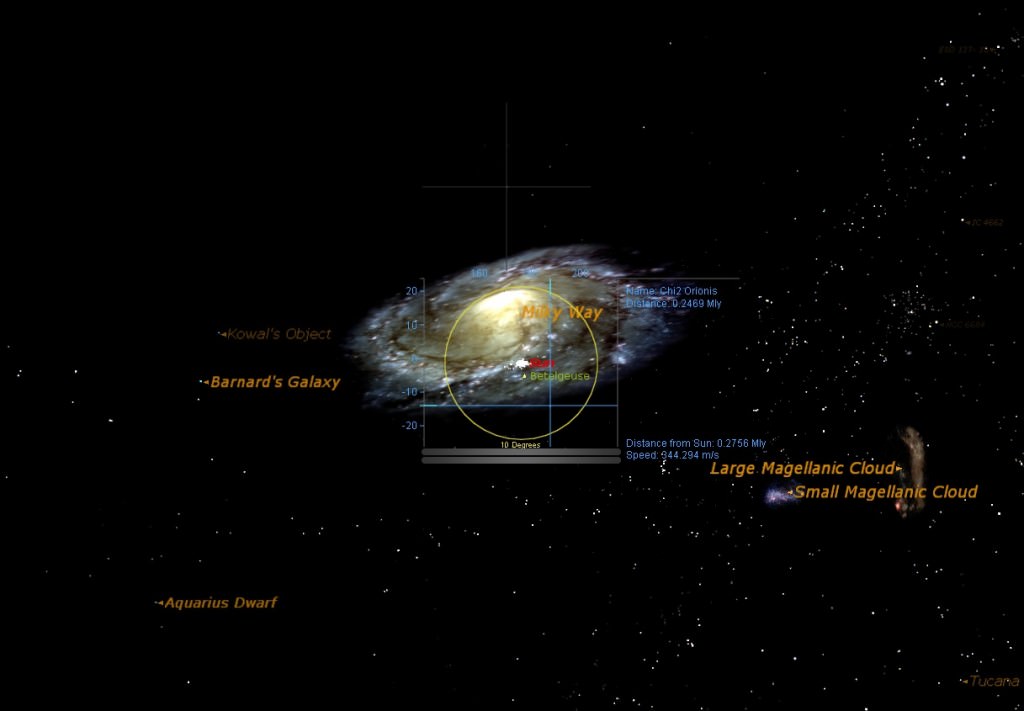

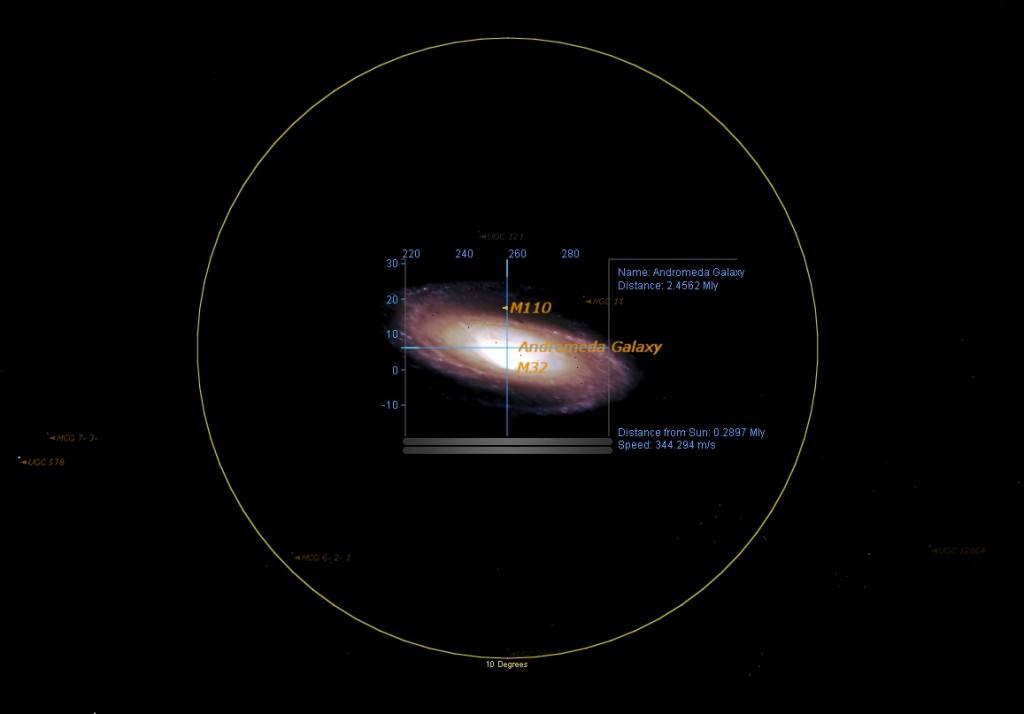

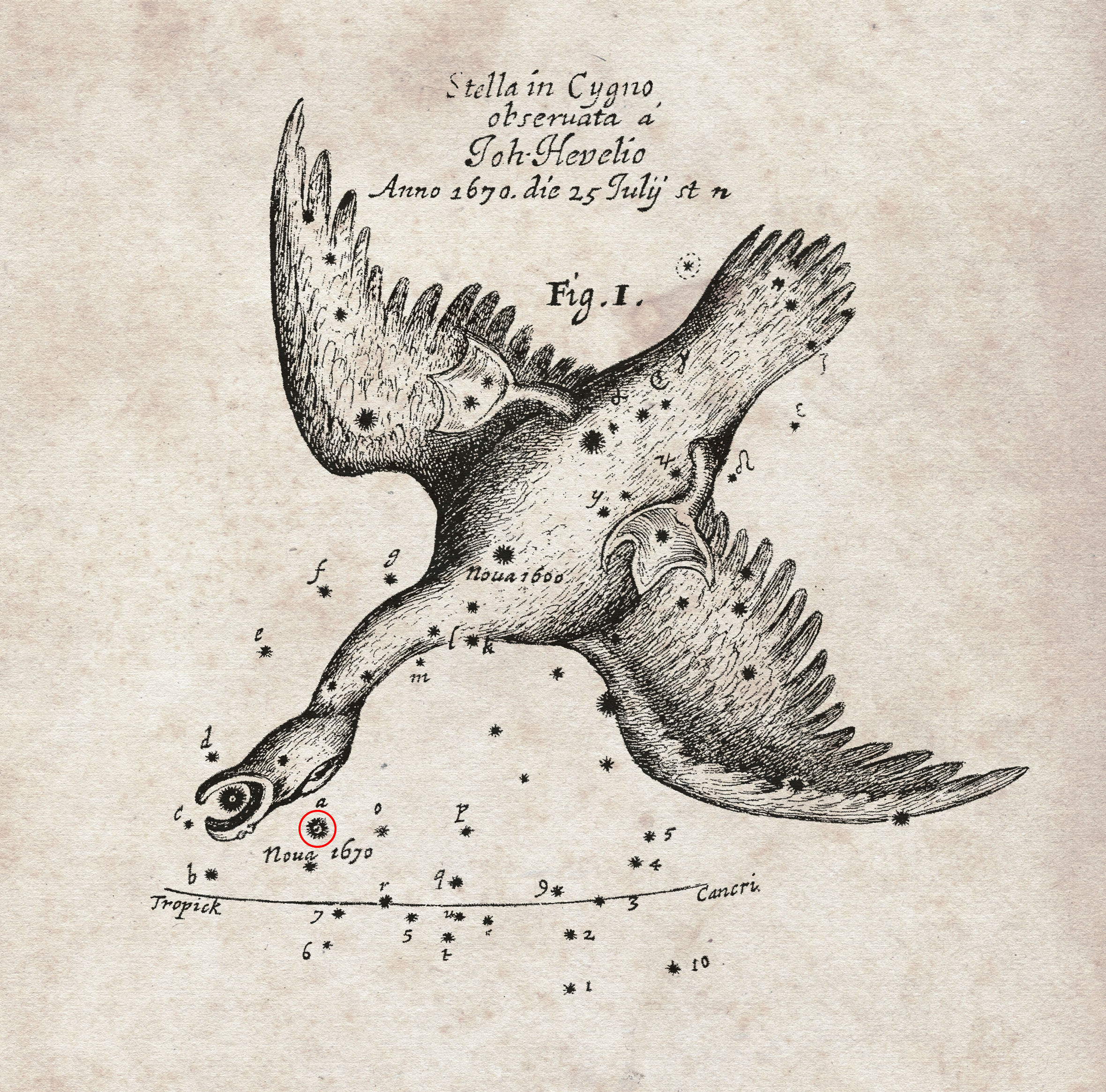

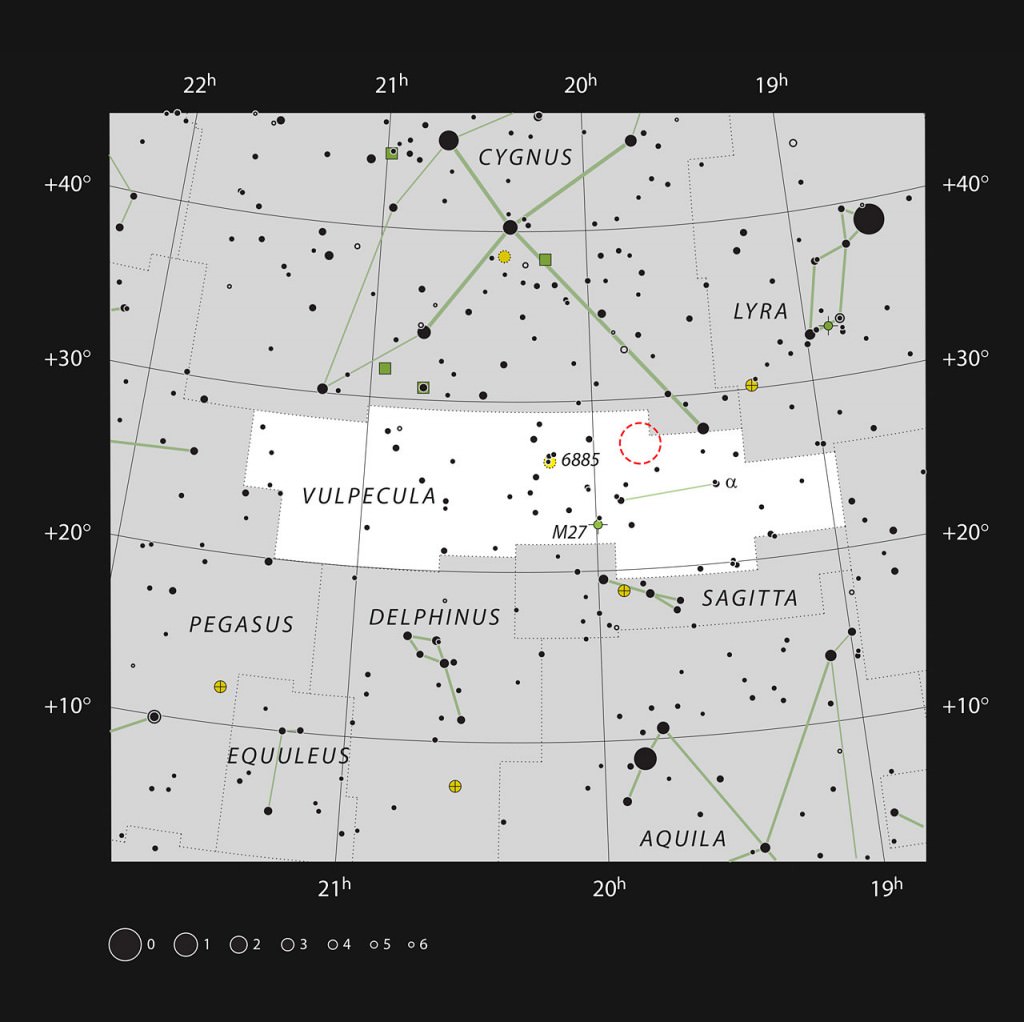

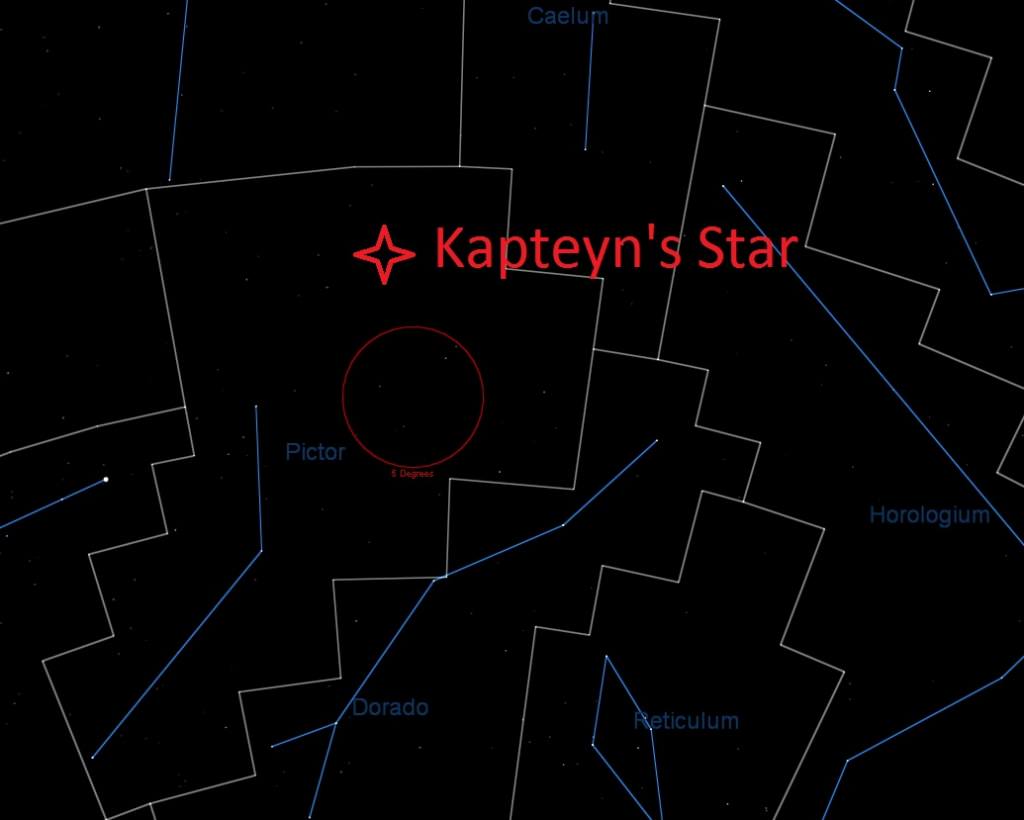

Discovered due to its high (8 arc seconds per year) proper motion by Dutch astronomer Jacobus Kapteyn in 1898, Kapteyn’s Star is the closest known halo star to our solar system. It’s thought that Kapteyn’s Star might be associated with the large globular cluster Omega Centauri, which itself is thought to be the remnant of a dwarf galaxy gobbled up by our own Milky Way in the distant past.

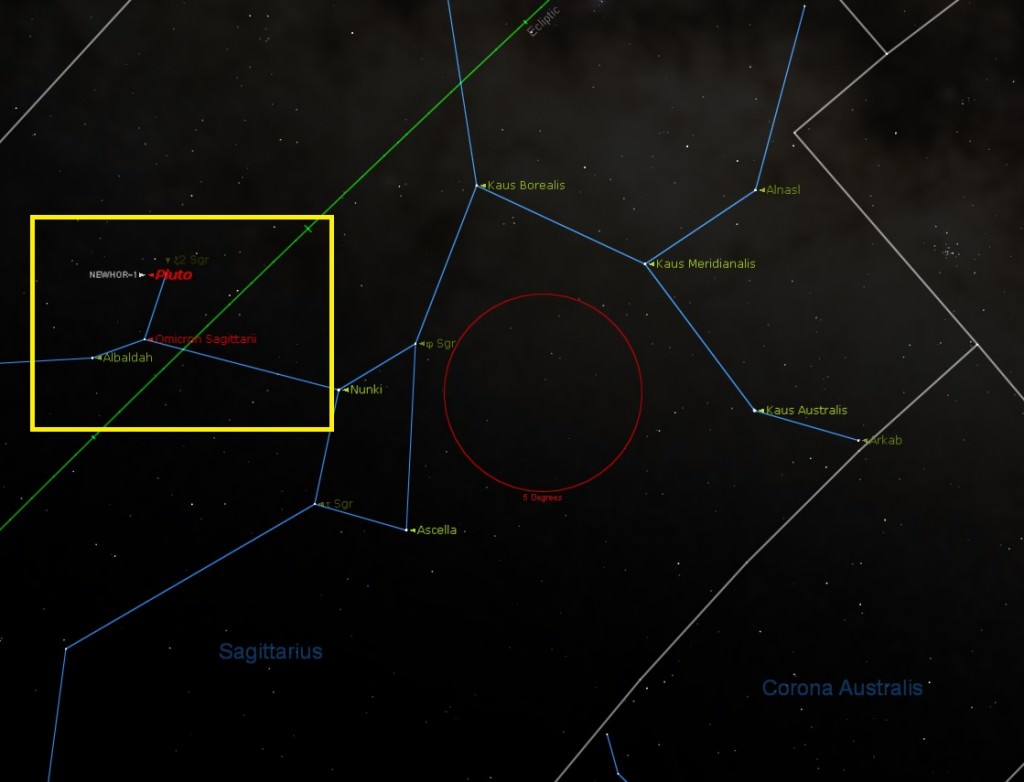

Kapteyn-b also made our list of red dwarf stars visible in backyard telescopes.

And Kapteyn-b wouldn’t be the first exoplanet detection that turned out to be spurious, as the existence of the exoplanet Alpha Centuari Bb announced in 2012 has been called into question as well.

It’s a brave new world on exoplanet science out there for sure, and for now, the worlds of Kapteyn’s Star will remain a mystery.