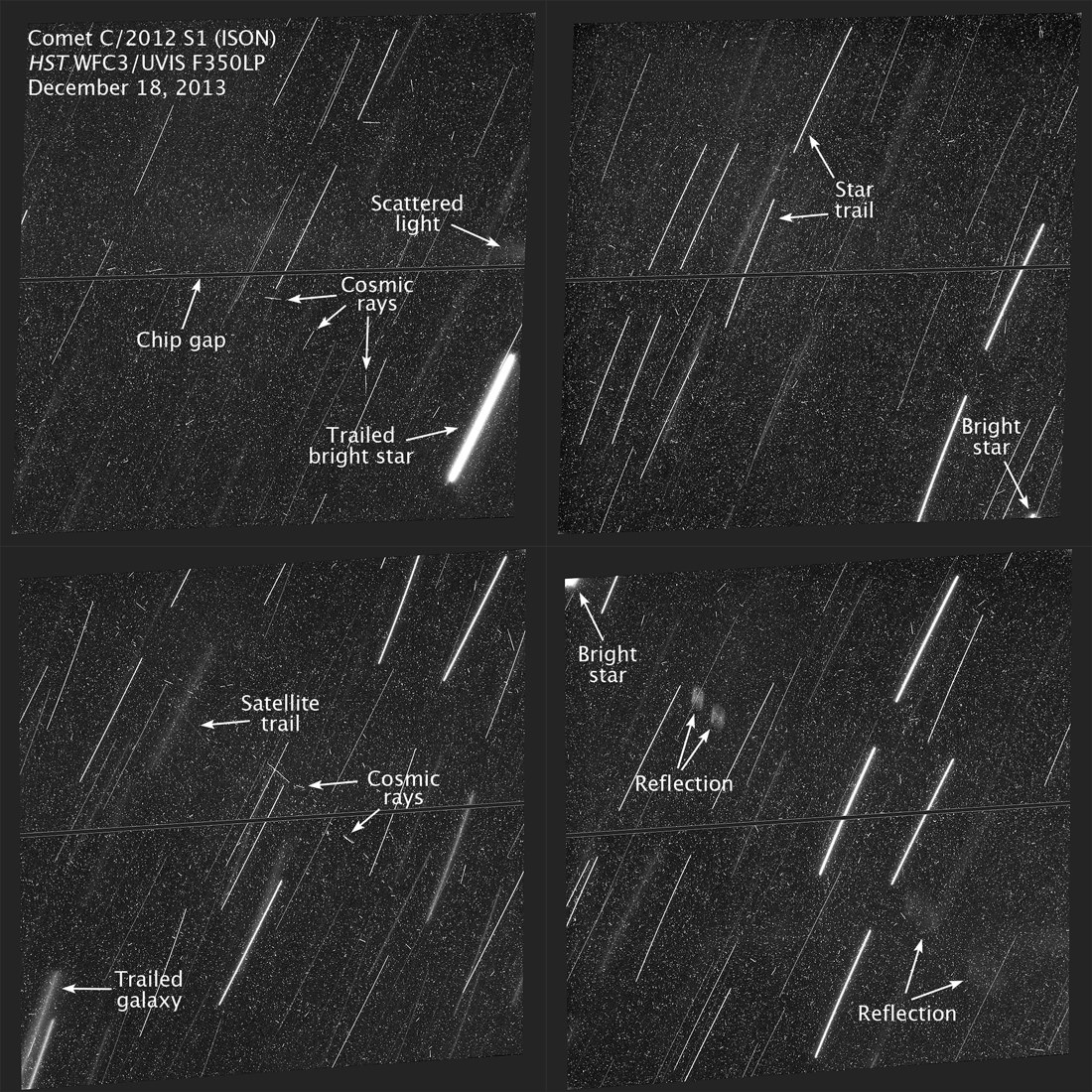

As 2014 opens, most of the half dozen comets traversing the morning and evening sky are faint and require detailed charts and a good-sized telescope to see and appreciate. Except for Comet Lovejoy. This gift to beginner and amateur astronomers alike keeps on giving. But wait, there’s more. Three additional binocular-bright comets will keep us busy starting this spring.

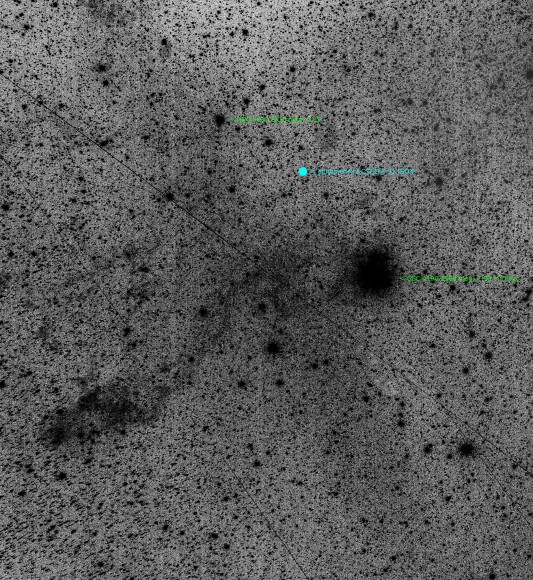

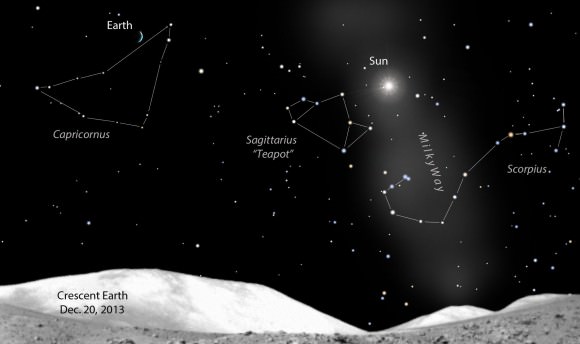

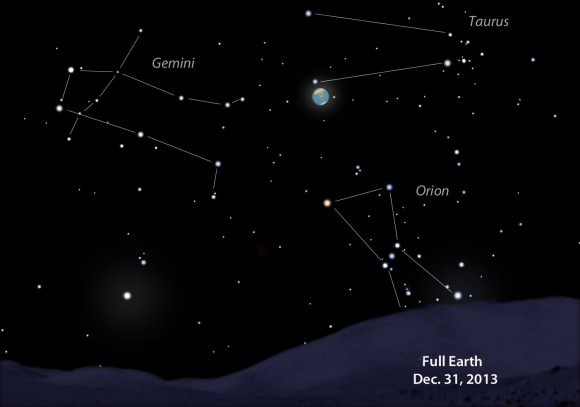

Still glowing around the naked eye limit at magnitude 6, the Lovejoy remains easy to see in binoculars from dark skies as it tracks from southern Hercules into Ophiuchus in the coming weeks.

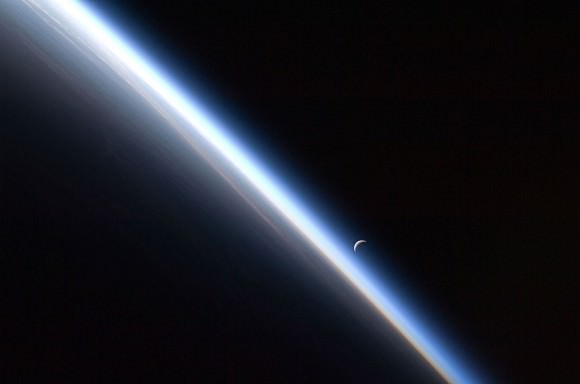

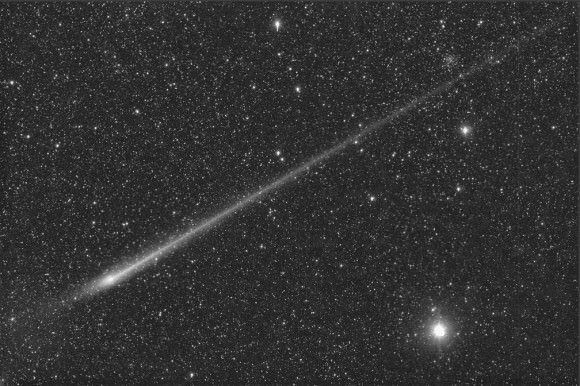

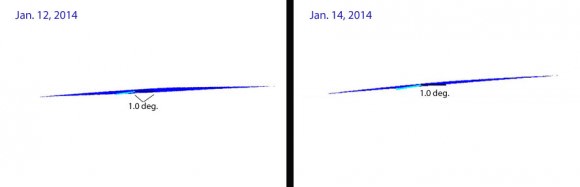

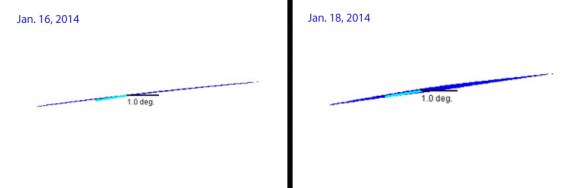

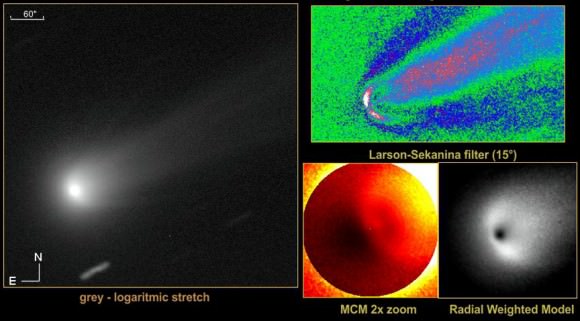

The best time to view the comet is shortly before the start of dawn when it sails highest in the eastern sky at an altitude of around 30 degrees or “three fists” up from the horizon. By January’s end, the comet will still be 25 degrees high in a dark sky. My last encounter with Lovejoy was a week ago when 10×50 binoculars revealed a bright coma and 1.5 degree long tail to the northwest. Through the telescope the stark contrast between bright, compact nucleus and gauzy coma struck me as one of the most beautiful sights I’d seen all month.

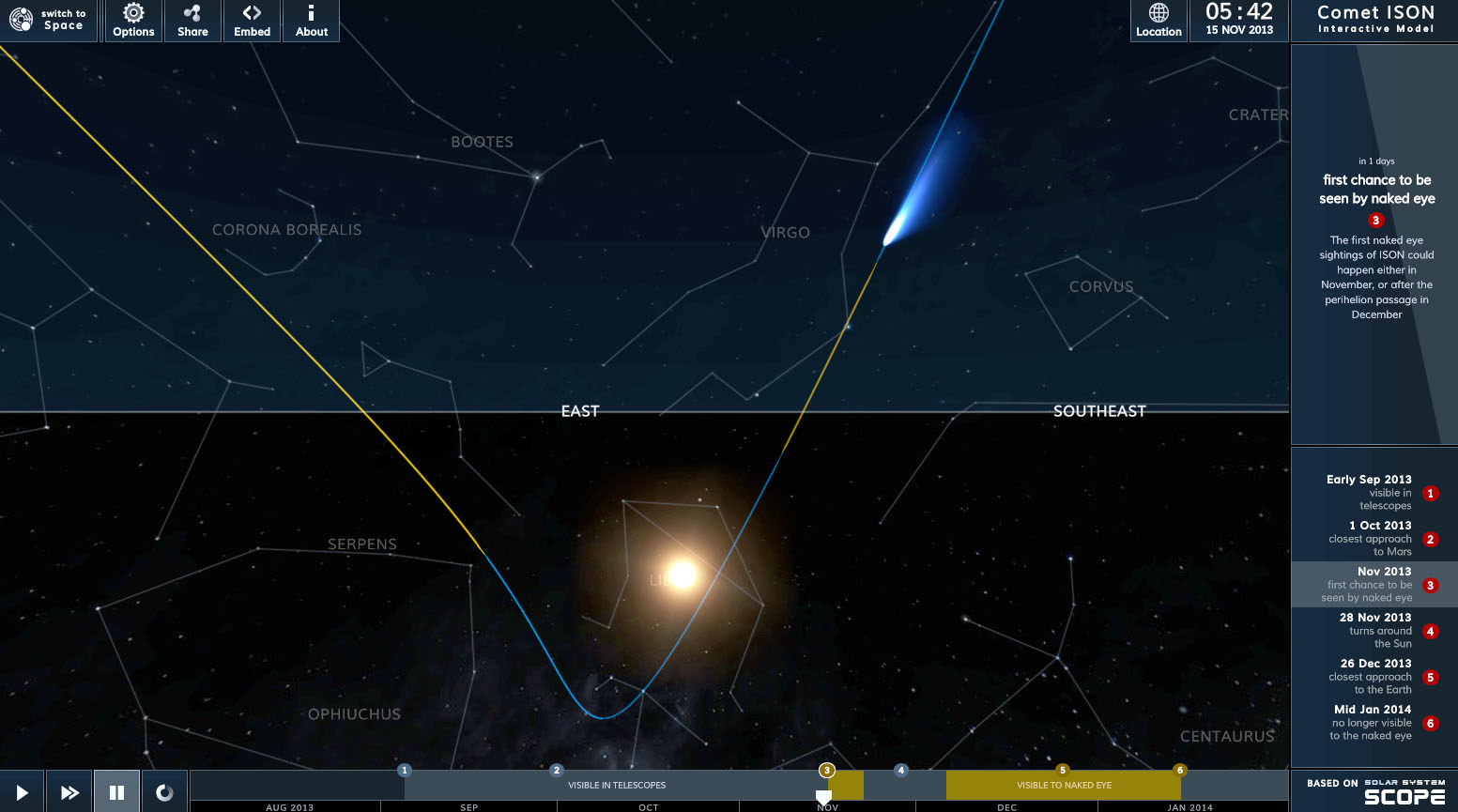

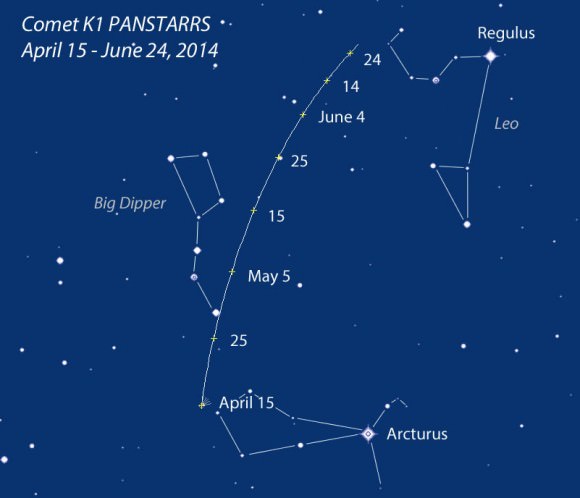

Looking ahead to 2014 there are at present three comets beside Lovejoy that are expected to wax bright enough to see in binoculars and possibly with the naked eye: C/2012 K1 PanSTARRS, C/2013 V5 Oukaimeden and C/2013 A1 Siding Spring The first lurks in Hercules but come early April should bulk up to magnitude 9.5, bright enough to track in a small telescope for northern hemisphere observers. Watch K1 PANSTARRS amble from Bootes across the Big Dipper and down through Leo from mid-spring through late June hitting magnitude 7.5 before disappearing in the summer twilight glow. K1 will be your go-to comet during convenient viewing hours.

Come early September after K1 PANSTARRS leaves the sun’s ken, it reappears in the morning sky, traveling westward from Hydra into Puppis. Southern hemisphere observers are now favored, but northerners won’t suffer too badly. The comet is expected to crest to magnitude 5.5 in mid-October just before it dips too far south for easy viewing at mid-northern latitudes.

Comet C/2013 V5 (Oukaimeden), discovered November 15 at Oukaimeden Observatory in Marrekesh, Morocco. Preliminary estimates place the comet at around magnitude 5.5 in mid-September. It should reach binocular visibility in late August in Monoceros the Unicorn east of Orion in the pre-dawn sky before disappearing in the twilight glow for mid-northern latitude observers. Southern hemisphere skywatchers will see the comet at its best and brightest before dawn in early September and at dusk later that month.

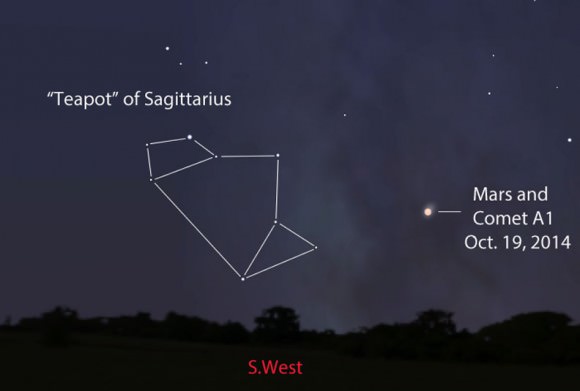

2014’s most anticipated comet has to be C/2013 A1 Siding Spring, expected to reach magnitude 7.5 and become binocular-worthy for southern hemisphere skywatchers as it traverses the southern circumpolar constellations this September. Northerners will have to wait until early October for the comet to climb into the evening sky by way of Scorpius and Sagittarius. Watch for an 8th magnitude hazy glow in the southwestern sky at that time.

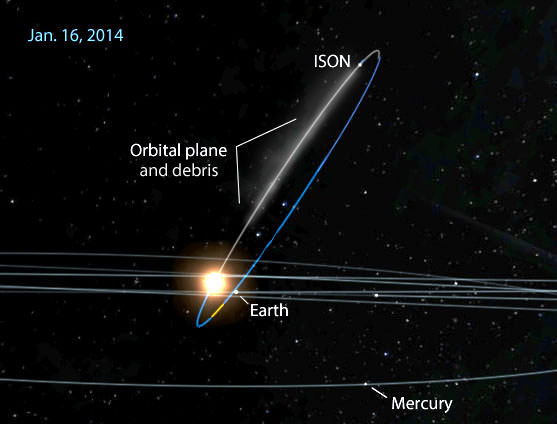

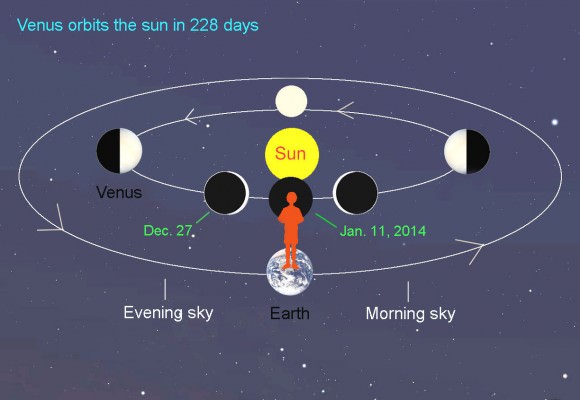

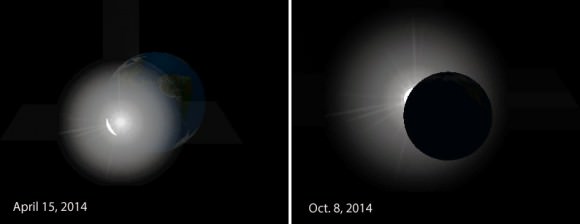

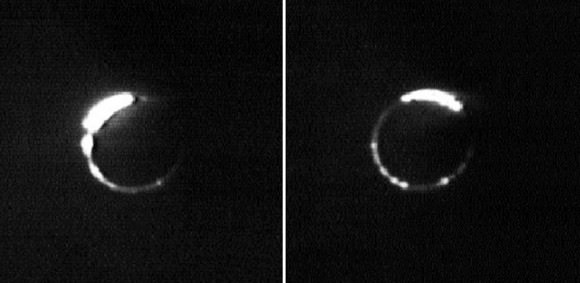

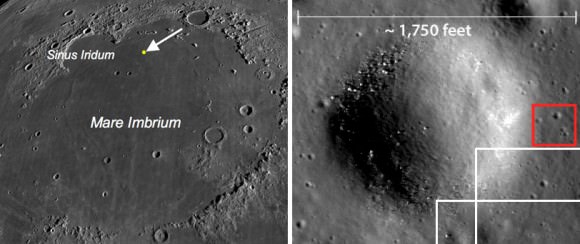

As October ticks by, A1 Siding Spring creeps closer and closer to Mars until it overlaps the planet on the 19th. Normally, a comet will only appear to pass in front of stars and deep sky objects because it’s in the same line of sight. Not this time. Siding Spring may actually “touch” Mars for real.

On October 19 the comet will pass so close to the planet that its outer coma or atmosphere may envelop Mars and spark a meteor shower. The sight of a bright planet smack in the middle of a comet’s head should be something quite wonderful to see through a telescope.

While the list of predicted comets is skimpy and arguably not bright in the sense of headliners like Hale-Bopp in 1997 or even L4 PANSTARRS from last spring, all should be visible in binoculars from a dark sky site.

Every year new comets are discovered, some of which can swiftly brighten and put on a great show like Comet Lovejoy (discovered Sept. 7) did last fall and continues to do. In 2013, 64 new comets were found, 14 of them by amateur astronomers. Comets with the potential to make us ooh and aah are out there – we just have to find them.