An international team of astronomers has figured out a way to determine details of an exoplanet’s atmosphere from 50 light-years away… even though the planet doesn’t transit the face of its star as seen from Earth.

Tau Boötis b is a “hot Jupiter” type of exoplanet, 6 times more massive than Jupiter. It was the first planet to be identified orbiting its parent star, Tau Boötis, located 50 light-years away. It’s also one of the first exoplanets we’ve known about, discovered in 1996 via the radial velocity method — that is, Tau Boötis b exerts a slight tug on its star, shifting its position enough to be detectable from Earth. But the exoplanet doesn’t pass in front of its star like some others do, which until now made measurements of its atmosphere impossible.

Today, an international team of scientists working with the Very Large Telescope (VLT) at ESO’s Paranal Observatory in Chile have announced the success of a “clever new trick” of examining such non-transiting exoplanet atmospheres. By gathering high-quality infrared observations of the Tau Boötis system with the VLT’s CRIRES instrument the researchers were able to differentiate the radiation coming from the planet versus that emitted by its star, allowing the velocity and mass of Tau Boötis b to be determined.

Today, an international team of scientists working with the Very Large Telescope (VLT) at ESO’s Paranal Observatory in Chile have announced the success of a “clever new trick” of examining such non-transiting exoplanet atmospheres. By gathering high-quality infrared observations of the Tau Boötis system with the VLT’s CRIRES instrument the researchers were able to differentiate the radiation coming from the planet versus that emitted by its star, allowing the velocity and mass of Tau Boötis b to be determined.

“Thanks to the high quality observations provided by the VLT and CRIRES we were able to study the spectrum of the system in much more detail than has been possible before,” said Ignas Snellen with Leiden Observatory in the Netherlands, co-author of the research paper. “Only about 0.01% of the light we see comes from the planet, and the rest from the star, so this was not easy.”

Using this technique, the researchers determined that Tau Boötis b’s thick atmosphere contains carbon monoxide and, curiously, exhibits cooler temperatures at higher altitudes — the opposite of what’s been found on other hot Jupiter exoplanets.

“Maybe one day we may even find evidence for biological activity on Earth-like planets in this way.”

– Ignas Snellen, Leiden Observatory, the Netherlands

In addition to atmospheric details, the team was also able to use the new method to determine Tau Boötis b’s mass and orbital angle — 44 degrees, another detail not previously identifiable.

“The new technique also means that we can now study the atmospheres of exoplanets that don’t transit their stars, as well as measuring their masses accurately, which was impossible before,” said Snellen. “This is a big step forward.

“Maybe one day we may even find evidence for biological activity on Earth-like planets in this way.”

This research was presented in a paper “The signature of orbital motion from the dayside of the planet Tau Boötis b”, to appear in the journal Nature on June 28, 2012.

Read more on the ESO release here.

Added 6/27: The team’s paper can be found on arXiv here.

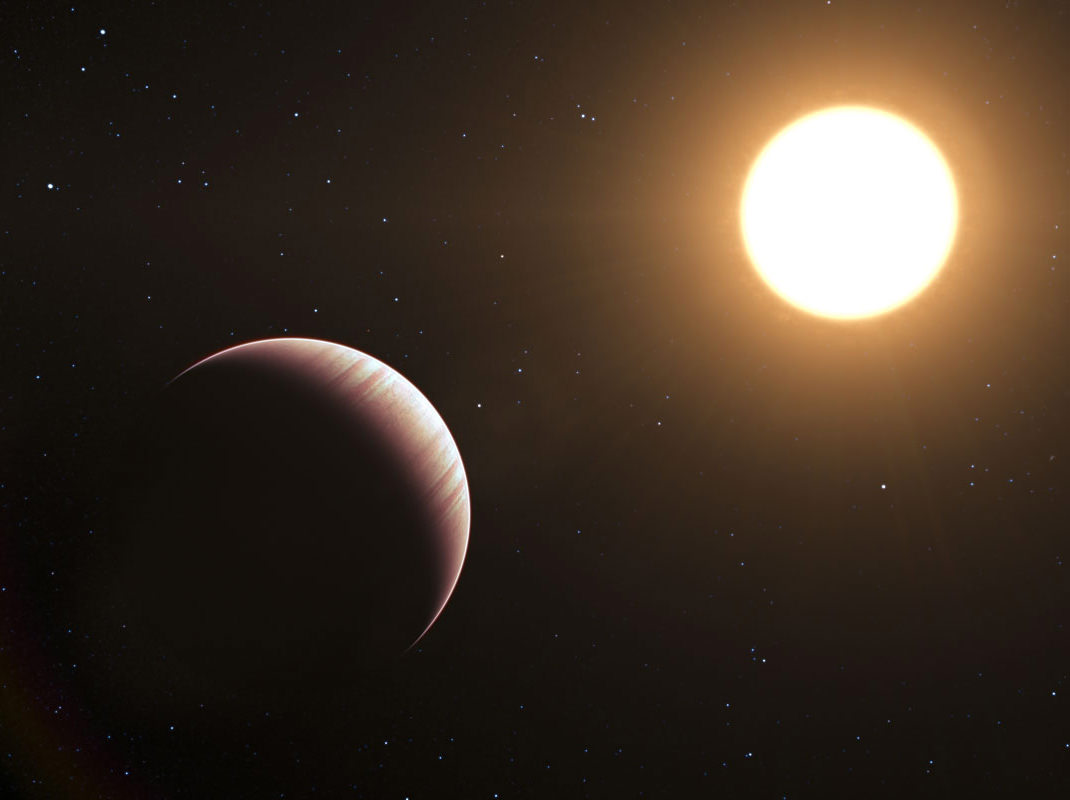

Top image: artist’s impression of the exoplanet Tau Boötis b. (ESO/L. Calçada). Side image: ESO’s VLT telescopes at the Paranal Observatory in Chile’s Atacama desert. (Iztok Boncina/ESO)

Here are two relevant (PDF) papers:

The radial velocity trail from the giant planet orbiting ? Boötis;

Exoplanet-atmospheres at high spectral resolution: A CRIRES survey of hot-Jupiters.

Ingenious! They correlate the known planet velocity from its known orbit with spectroscopic variation and can tease out what is light and its absorption from the planet (vs say star emission/absorption or Earth atmosphere absorption).

I assume they will need some orbits to get reliable results, in which case observing Earth analogs will be slightly less appealing. But maybe not.

Amazing what we can tease from literally nothing more than a point of light.

I love this stuff, the clever detective work , each mystery unravelled helping to know the next unknown, this and the awesomeness of it all is what does it for me.