[/caption]

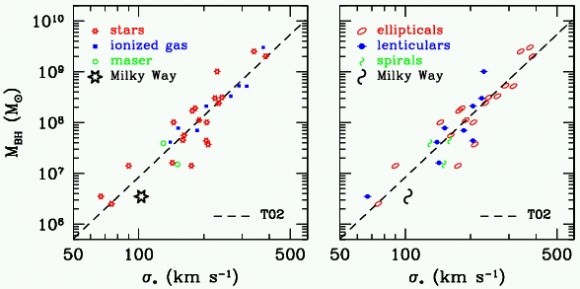

While only observable by inference, the existence of supermassive black holes (SMBHs) at the centre of most – if not all – galaxies remains a compelling theory supported by a range of indirect observational methods. Within these data sources, there exists a strong correlation between the mass of the galactic bulge of a galaxy and the mass of its central SMBH – meaning that smaller galaxies have smaller SMBHs and bigger galaxies have bigger SMBHs.

Linked to this finding is the notion that SMBHs may play an intrinsic role in galaxy formation and evolution – and might have even been the first step in the formation of the earliest galaxies in the universe, including the proto-Milky Way.

Now, there are a number of significant assumptions built into this line of thinking, since the mass of a galactic bulge is generally inferred from the velocity dispersion of its stars – while the presence of supermassive black holes in the centre of such bulges is inferred from the very fast radial motion of inner stars – at least in closer galaxies where we can observe individual stars.

For galaxies too far away to observe individual stars – the velocity dispersion and the presence of a central supermassive black hole are both inferred – drawing on the what we have learnt from closer galaxies, as well as from direct observations of broad emission lines – which are interpreted as the product of very rapid orbital movement of gas around an SMBH (where the ‘broadening’ of these lines is a result of the Doppler effect).

But despite the assumptions built on assumptions nature of this work, ongoing observations continue to support and hence strengthen the theoretical model. So, with all that said – it seems likely that, rather than depleting its galactic bulge to grow, both an SMBH and the galactic bulge of its host galaxy grow in tandem.

It is speculated that the earliest galaxies, which formed in a smaller, denser universe, may have started with the rapid aggregation of gas and dust, which evolved into massive stars, which evolved into black holes – which then continued to grow rapidly in size due to the amount of surrounding gas and dust they were able to accrete.

Distant quasars may be examples of such objects which have grown to a galactic scale. However, this growth becomes self-limiting as radiation pressure from an SMBH’s accretion disk and its polar jets becomes intense enough to push large amounts of gas and dust out beyond the growing SMBH’s sphere of influence. That dispersed material contains vestiges of angular momentum to keep it in an orbiting halo around the SMBH and it is in these outer regions that star formation is able to take place. Thus a dynamic balance is reached where the more material an SMBH eats, the more excess material it blows out – contributing to the growth of the galaxy that is forming around it.

To further investigate the evolution of the relationship between SMBHs and their host galaxies – Nesvadba et al looked at a collection of very red-shifted (and hence very distant) radio galaxies (or HzRGs). They speculate that their selected group of galaxies have reached a critical point – where the feeding frenzy of the SMBH is blowing out about as much material as it is taking in – a point which probably represents the limit of the active growth of the SMBH and its host galaxy.

From that point, such galaxies might grow further by cannibalistic merging – but again this may lead to a co-evolution of the galaxy and the SMBH – as much of the contents of the galaxy being eaten gets used up in star formation within the feasting galaxy’s disk and bulge, before whatever is left gets through to feed the central SMBH.

Other authors (e.g. Schulze and Gebhardt), while not disputing the general concept, suggest that all the measurements are a bit out as a result of not incorporating dark matter into the theoretical model. But, that is another story…

Further reading: Nesvadba et al. The black holes of radio galaxies during the “Quasar Era”: Masses, accretion rates, and evolutionary stage.

If these observations of spectral broadening can be extended to the most distant galaxies we might observe how SMBHs form in the first place. This would suggest that SMBH formation might be accompanied by the rapid formation of the earliest galaxies.

LC

There is more.

I believe LC laid out in a comment on the “Jets” thread how BHs explains overcoming and regulating angular momentum in whole.

Also, I seem to remember a paper looking at star birth rate in galaxies, which distribution has to be disentangled from aging and what not. Doing it properly seemed to predict that formation rate was tightly regulated by feed back.

Now, as I can’t find the paper I don’t know if it connects. But conversely, the SMBH results should suggest a birth rate regulation, if I understand it correctly.

Speculating then, star birth would pull (into stars) and push (radiation) matter away from the SMBH star production engine, constituting a negative feedback regulating loop. The figures constitute a test for _some_ type of feedback from a bottleneck.

But is it the SMBH regulating itself, or is the surrounding galaxy/star birth responsible? The former is simpler, the later is more poetic – and the paper gives the answer, I think; the kinetic/radiative energy balance is explained by the SMBH alone (fig 5). Neat!

“… LC laid out in a comment …”, and others, I remember now.

“the mass of a galactic bulge is generally inferred from the velocity dispersion of its stars ”

I don’t really understand this. Does “its stars” relate to the bulge, or the whole galaxy? And why should it be the dispersion, rather than the average velocity?

Other questions: SMBHs vary in mass from millions to billions of solar masses. Do bulges vary in the same proportion? What is the current understanding about the reasons for this important variation?

Its most plausible to think of ‘whatever’ we are indirectly observing in galaxy center’s as formative to a their existence and structure. What is not being asked is what purpose it serves.

I personally like thinking of galaxies as a star factory’s. Turning base interstellar hydrogen into stars that further turn it into heavier metals. The jets emanating from the centers of our proposed SMBH could be the engine of a galaxy that achieve this task.

Why the universe has or needs such factories is yet another question.

I feel it has to be tied to entropy, which creates ever more complex and energy efficient systems. Yes they are ultimately a lower energy state but also far more interesting from a sentient perspective. 🙂

SMBH production most likely had to begin with the end of the radiation dominated period. The entropy of the universe was low at the start, which means there were not likely black holes that emerged in the quantum tunneling or instanton that defined the preinflationary universe. Inflation precluded any possible BH formation after that. Then with the reheating phase where the inflaton potential became a quadratic potential the universe entered the radiation period. BH formation was again unlikely then as well. Yet it does appear that within 5e^8 years galaxies and probably large BHs were alive and kicking.

With these giant telescope planned it should be possible to peer into the hearts of these earliest galaxies to determine in the SMBHs were established then or prior to then. These data suggest a linear relationship between the size of galactic bulges and SMHBs, which as a sort of standard model might be considered or tested ally the way back to the earliest period of galaxy formation.

The stars “relate” to the bulge in that the larger the bulge the larger is the gravitational potential which holds these stars. This means their velocities are larger. It is like a swarm of angry bees, the larger the swarm the faster the bees fly around each other.

LC

Ah, um, well.

First, the overall reason there is dust to create stars can be found in environmental principles, which maximize life where there is dust. It isn’t tied to entropy as such, though without a sufficiently expanding universe you would have neither dust nor possible entropy increase from its expansion.

Second, gravitation is counterintuitive when we discuss entropy, it is the negative specific heat capacity of a gravitational cloud that let it shrink, but it looses entropy (and its energy, of course) all the same. It is the universe at infinity that gets the entropy increase with the heat radiation.

BHs messes that “simple” picture up by being gravitational systems, yet gaining entropy – for a while. A forward infinite time FLRW universe outlives the suckers, whereupon presumably a evaporating BH gives its entropy back to the universe.

Since galaxies emits heat, I would simply guess that as a mainly gravitational system it has an overall entropy loss.

Third, it doesn’t make much sense to say that entropy creates ever more complex systems.

The dust production is related but not primary out of the entropy process, it is a selection effect.

Evolution is related but not primary out of the entropy process, again a selection effect and actually lowering entropy locally. But very little, estimates puts it at a 10^-8 decrease compared to Earth entropy production out of mediating sun light to the environment. (I have the ref, if asked.)

[As for energy efficiency, I dunno what to make of it. The best energy efficiency I know of is optical absorption quantum efficiency in silicon crystals and such like. That is more a “dust” system than an “evolution” system, random outcome. Not surprisingly, since evolution is a local hill climber, not an optimizing algorithm – it would take an infinite population infinite time to resolve a local maxima precisely.

Again, neither “dust” nor “evolution” as processes has directly to do with entropy as a process.]

So the Eddington limit results in a very stable situation, or does the condensation of the rotating dust disk into stars create stable orbits and starve the SMBH? Does this mean that active galaxies always turn into normal galaxies when that equilibrium is reached? More interesting though is LC’s comment about where the SMBH came from in the first place.

More precisely perhaps, in the face of the competing mechanism of near neutral drift, it would take that population to avoid drifting away entirely as it increases “signal” (sees smaller fitness) and suppresses “noise” (avoids stochastic drift fixation of alleles).

I dunno if anyone have made a comparison of the two, to say what would happen. Probably not, because the result is that in practice evolution “makes do”, it is enough to be sufficiently fecund compared with (extinction and) competition.

Oy vey, now I’m expanding on a parenthesis! I’ll take my coat and leave now…

…to me it seems only logical that any (spiral) galaxy MUST have a black hole in its center… giving it the descriptive spiral design, derived from the “motor” in its midst.

It also seems logical to assume that an ‘unorganized’ galaxy or heap of stars does not have a black hole in its center. So-called old galaxies may have had a black hole in its center which became inactive…

I am not a scientist, but have been interested in astronomy and cosmology from a philosophical point of view. So forgive me for not being too scientific.

The effective heat capacity of spacetime is negative. This has several strange consequences. The temperature of a black hole T = hbar c^3/(8pi GMk), (hbar = unit of action, k = Boltzmann constant, G = gravitation constant, c = speed of light) decreases with the mass of the black hole, and the entropy S = A/4L_p^2, for A = 4pi R^2 and R = Schwarzschild radius = 2GM/c^3 increases with mass. This is the meaning of the negative heat capacity of spacetime. This is opposite of most standard thermodynamic systems that have zero entropy as t – -> 0. Quantum mechanically this mean if a black hole quantum radiates a unit of mass-energy in a boson &m then the reduced mass of the black hole m – &m results in higher temperature and lower entropy. The entropy is liberated to the exterior world, so this does not violate thermodynamics. Similarly if a black hole increases its entropy by absorbing a unit of mass energy &m its temperature declines. This has a curious consequence, for in a model system a black hole has no equilibrium. If a black hole sits in a box with a temperature background equal to its horizon temperature it will not remain there. If it emits a quantum with mass-energy &m it then is hotter than the back ground and will tend to heat up further and quantum radiate away. If instead it absorbs a quantum from the background it becomes cooler and will then increase in mass, get colder and run off in that direction. There is no equilibrium.

There is only one sort of “box” which can hold a black hole, that is an anti de Sitter spacetime. The negative curvature of that spacetime is such that one can place a black hole “eternally” in one. That gets into some frontier issues with physics and cosmology, which I will not delve into for now.

Another consequence of black holes on an astrophysical front is that as their entropy increases and their temperature decreases they becomes enormous heat sinks for external mechanisms. It is for this reason that the MHD mechanism for jets in quasars, micro-quasars and AGNs are extremely efficient. They have thermodynamic efficiencies around 90%, which is astounding. The thermodynamic efficiencies of our heat engines (internal combustion engines, turbines etc) run around 30-40% efficient, and our practical devices are at best half of that. The reason for this huge efficiency is heat flow into zero temperature regions are 100% efficient (one reason for the 3rd law of thermodynamics) and the horizon of a black hole is pretty darn close to zero temperature. It may be by extension that the kinetic energy processes the SMBH induce in a galaxy may also be extremely efficient.

LC

“…to me it seems only logical that any (spiral) galaxy MUST have a black hole in its center… giving it the descriptive spiral design, derived from the “motor” in its midst.”

But we do know of many spiral galaxies that do not posses a central SMBH, even ones in a quiescent state. M 33, NGC 300 and NGC 5907 come to mind. But these three examples are also less massive and have a smaller or non-existent bulge component compared to the Milky Way or Andromeda galaxies (also, SMBHs are not thought to drive the formation of spiral arms). As you mentioned, irregular galaxies are not thought, in general, to contain SMBHs. Likewise with dwarf spheroidal, dwarf elliptical and tidal dwarf galaxies.

So the total mass of a galaxy seems to have some bearing on whether it contains a SMBH or not. The question remains though as to the role of SMBHs in galaxy formation.

@ manu

Velocity dispersion tells you about the mass of the bulge as others have explained (gravity potential) – essentially you measure velocities at different radii to get the parameters of the gravity well: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Velocity_dispersion

It’s impractical trying to calculate bulge mass from counting the number of stars, either because there are so many – or the galaxy is far, far away and you can’t see them.

@stevezodiac

“So the Eddington limit results in a very stable situation, or does the condensation of the rotating dust disk into stars create stable orbits and starve the SMBH? ”

Eddington luminosity pushes material away from the SMBH’s sphere of influence (starving it). Whether or not this material condenses is not immediately relevant (i.e. it’s out of the picture anyway). But new gas coming into the system may be depleted in bulge star formation – which does hence further ‘starve’ the SMBH. And yes, the suggestion is that they all quieten down after the SMBH depletes its accretion disk (unless cannibalistic merging starts things up again).

@ikepod

“…to me it seems only logical that any (spiral) galaxy MUST have a black hole in its center… giving it the descriptive spiral design, derived from the “motor” in its midst.”

I’m not sure this is a given. You can find stable celestial geometries (e.g. globular clusters) that don’t need a central massive object. An SMBH does not have enough gravity to significantly influence the large scale structure of a galaxy. The idea of an SMBH ‘engine’ is generally used in the context of active galactic nuclei (AGN) – i.e. it is the major source of AGN radiation outburst and jets.

As Jon points out, the SMHB is not a main driver of a galaxy structure and dynamics. The SMBH in the Milky ways is only 10e^6 times solar mass, and the galaxy has 3e^11 stars. So in our case the SMBH is not a main determinant of galactic dynamics. From what I understand there are some SMBHs that are in the 10-100 billion solar mass range, and there you might have serious galactic structure result from these. However, in any case around 70% of matter is still dark matter.

I am not that familiar with the physics, but galactic arms are thought to arise from density waves. These are not at all determined by the SMBH, at least from my understanding.

In the above I wrote that the Schwarschild radius is R = 2GM/c^3, when in fact it is 2GM/c^2.

LC

I’m surprised that the bar hasn’t had a mention in this discussion. Any speculation as to it’s relation to the SMBH dynamics?

@ wjwbudro

Bars are suggested to arise from orbital resonances in the galactic disk – so it’s unlikely the SMBH has a role in their development. However, since the bar acts as a route to channel gas from the arms to the centre of the galaxy, there is a correlation between bars and AGN – all that gas is fresh food for the SMBH, making it actively radiate (i.e. accretion disk, jets etc).

Why is there a rule of conservation of momentum in this universe in the first place?

[Not a stupid question, I hope 🙂 ].

It think it all must have something to do with the original state of the universe, imho.

One should make a study of the apparent increase of momentum in galaxy’s -regarding time, because :

– Our early universe does not show a preferred type of distribution of stars.

– Our lately universe does have a preferred type of distribution. SPIRAL galaxy’s are the preferred type. Not ellipticals.

This should have to do with the mechanism involved. [Hello Big Bang, are you involved somehow !? ]

What does a “SMBH” accomplish exactly, apart from showing a difference in local circumstances regarding the alignment of all the atoms in the galaxy in respect to the atomic configuration during Big Bang’s inflational period [function: time and distance] ?

Yes, but it seems to affect star production (when it is there), doesn’t it?

Stevezodiac:

It *is* puzzling.

To assume a “pre-inflationary universe” as LC does is an unnecessary and unsupported model assumption. We can strictly assume, for the time being, that there are no BHs around when inflation stops in standard inflationary cosmology, as LC notes.

But neither were galaxies. I harken to the idea that galaxy formation and SMBH formation is somehow connected, even though it seems fast.

@ LC:

I never thought of that, trying to put a BH in equilibrium and working out the physics consequences. Mainly because cosmology should decide; but then again this is an interconnected subject!

My gut instinct is that BHs can’t “break” cosmology (so I assume what I like O.o), so they must be evaporating anyway. Likely the ground state of cosmology is never actually reached in finite time, as witnessed by our own positive cc. (Or else there is no BH radiation equilibrium despite appearers.)

Then you have to fix quantum fluctuations to that state, I guess. That is easy, they can’t take the BH with then. (Or at least put it in equilibria at the same time: unlikely.) 🙂

“despite appears” := stupid dictionary routine supervised by stupid user.

@ Torbjorn Larsson OM

Regarding my Entropy conjecture. I keep getting my disciplines mixed up. In information Technology, entropy is often confused in its terminology. Kolmogorov complexity or or algorithmic entropy can be applied to Theories centered around Complex Adaptive Systems. Which a galaxy can be defined as.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Complex_adaptive_system

That said, if the rules apply in information technology, then why not in cosmology. Anyway, I wish someone comes up with a theory for why simple hydrogen in interstellar space turns into complex systems like galaxies, suns, planets and ultimately biological sentience.

Schroedinger proposed Negentropy, but i think it was a work of fiction. This is where I get my energy efficiency.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Negentropy

Just to keep on topic, this is all in trying to understand what a galaxy does, (together with its alluded SMBH) rather then focusing specifically on its structure. I’m not alluding that it has purpose, just trying to define what it does by existing. Is this a ridiculous notion?

Damian

@ TL OM

“Yes, but it seems to affect star production (when it is there), doesn’t it?”

Well, its radiation prevents star production locally – but pushes/concentrates dust out to a certain region where star formation does take place, albeit at a distance well beyond the SMBH’s sphere of influence (at least that’s my understanding of the model).

In a nutshell, the SMBH is the seed from which a huge galaxy grows – though more through these feedback processes than by virtue of its direct gravitational influence.

@TL OM

I harken to the idea that galaxy formation and SMBH formation is somehow connected, even though it seems fast.

LC reckons 5e^8 years post radiation period, not very long. It would be enough to form very large Pop III stars which all explode into BHs, but is it enough to form SMBHs and galaxies as well?

TL OM, The anti de Sitter spacetime can hold a black hole both classically and quantum mechanically, Gauss’ law tells us that a spherical shell around a central gravity field can’t hold it. The Poisson equation nabla^2U = 4pi G rho gives a nonzero and variable gravity potential U when the surface of integration encloses a mass, and U = const when the surface encloses vacuum. In the case of a spherical shell a Gaussian surface encloses nothing, hence the potential inside is zero or constant. Dyson spheres and the like (ring worlds and other sci-fi fantasies) are not able to really trap the star inside them. By the same token there is no box which can contain a black hole. This means we can’t trap a black hole and set up an equilibrium situation where particles that enter it and quantum tunnel out of it are in equilibrium or ideally “controlled.” However, a theoretical box does exist and it is the anti de Sitter spacetime (AdS). A two dimensional version of the AdS_2 are the circle limit drawings Escher worked. This spacetime has a negative curvature, so it repels anything from the boundary, and the arcs which leave the boundary and re-enter it are geodesics which leave at v near the speed of light and return as v – -> 0. The mathematics for the two dimensional case is the Poincare disk. The 2 space plus 1 time version AdS_3 is interesting for one can place a black hole at the center of this spacetime and the black hole can’t escape. Further, any particle which quantum tunnels out of the black hole is matched by one which leaves the boundary of the AdS and enters the black hole. This is the BTZ black hole and it has some interesting features. One can further work the 3 Q-bit quantum information theory of the black hole, where categories of entanglements (bipartite entangled states, W-states, GHZ states etc) correspond to the configuration (extremal, BPS etc) of the black hole. This can be carried to higher dimensions as well, but that gets into deep work. This also leads to the AdS/CFT hypothesis, where the boundary of the AdS is dual to a quantum field theory on the conformal spacetime on the boundary.

What I wrote above pertains mostly to quantum black holes, where black holes of astrophysical dimensions are fairly standard classical black holes. One might think according to the large N = # quantum states limit with how quantum mechanics transitions into classical mechanics. The astrophysical black hole is a standard classical physical configuration of general relativity. It is also worth pointing out that even with super massive BHs that beyond 100 or 1000 times the Schwarzschild horizon radius R = 2GM/c^2 the gravitation is not significantly different from Newtonian physics. The motions of stars observed at the center of the Milky Way galaxy is largely Newtonian. It will require extraordinary resolution to image the physics of the accretion disk close to the SMBH.

LC

Over at ‘Brand X’ I found the following:

http://www.astronomynow.com/news/n1011/26jet/

Oops.. dang.. wrong link. My duh.. The title image made me jump w/o looking. http://www.universetoday.com/79898/j-e-t-s-jets-jets-jets/#more-79898