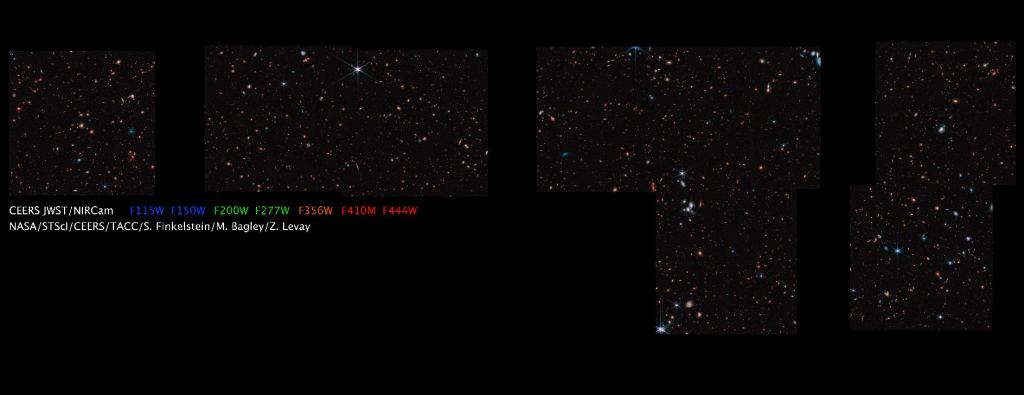

A team of scientists using the James Webb Space Telescope have just released the largest image taken by the telescope so far. The image is a mosaic of 690 individual frames taken with the telescope’s Near Infrared Camera (NIRCam) and it covers an area of sky about eight times as large as JWST’s First Deep Field Image released on July 12. And it is absolutely FULL of stunning early galaxies, many never seen before. Additionally, the team may have photographed one of the most distant galaxies yet observed.

The scientists, from the Cosmic Evolution Early Release Science Survey (CEERS) collaboration, said the mosaic is from a patch of sky near the handle of the Big Dipper. The images were taken as part of the first observations of the CEERS team, which is working to demonstrate that JWST can be used efficiently for performing extragalactic surveys, even while the telescope is performing other observations.

“This is JUST Epoch 1 of our observations,” said team member and astrophysicist Rebecca Larson, on Twitter. “We are less than halfway through our full survey, and already our data have led to new discoveries and an unexpected, but not unwelcome, abundance of never-before-seen galaxies.”

In a blog post on the CEERS website, Larson added encouraged everyone to open the high-resolution images, available here, to zoom in and explore. But a warning, the highest resolution versions of the images are ginormous, and it doesn’t really work to look at them on small screens like a phone.

“The sheer number of galaxies we have captured so far is awe-inspiring!” Larson said.

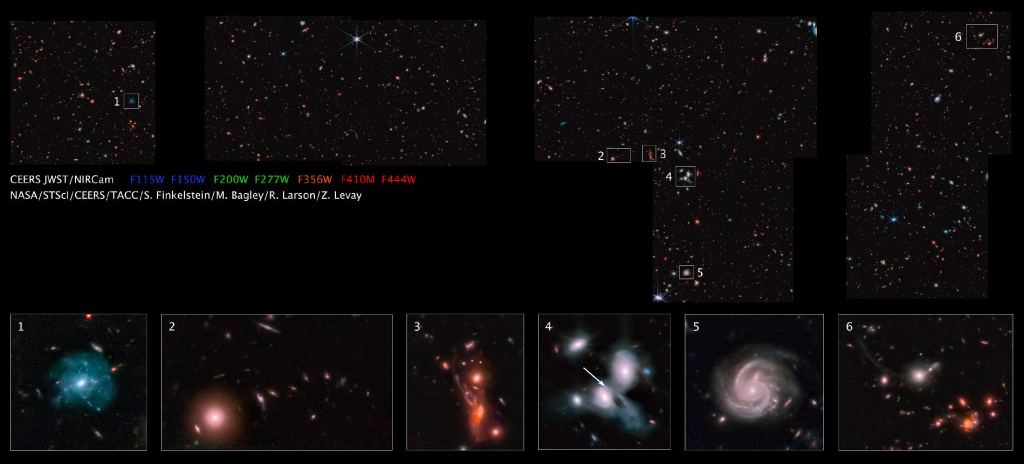

In the large mosaic, there are a few galaxies of note that are shown in the inset of the image above. First is a spiral galaxy at a redshift of z=0.16. The resolution of the JWST imaging reveals a large number of blue star-forming clumps and star clusters.

There’s also an interacting system of galaxies at 1.4 redshift, dubbed the “Space Kraken” by the CEERS team, as well as two interacting spiral galaxies at redshift z=0.7. The image below shows those galaxies as well as something unique: the arrow points to what is likely the first supernovae discovered with JWST images.

The other insets show a stunning spiral galaxy, which the team says highlights JWST’s ability to resolve smallscale features even for modestly distant galaxies, as well as a chance alignment of a galaxy with a tidal tail and group of red galaxies.

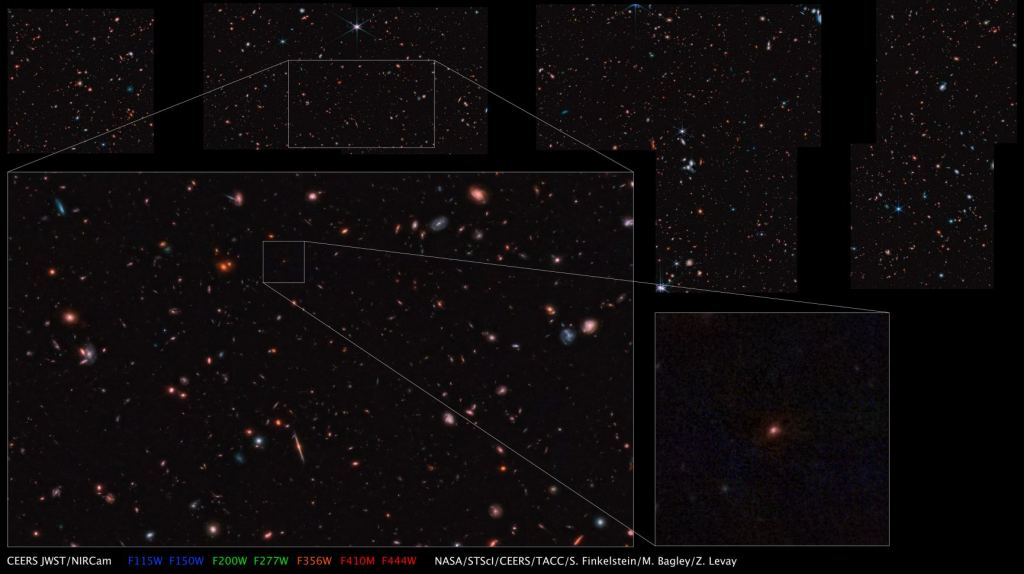

Scientists in the CEERS Collaboration have identified an object — dubbed Maisie’s galaxy in honor of project head Steven Finkelstein’s daughter — that may be one of the earliest galaxies ever observed. While the finding is awaiting confirmation, the team has put out a paper on it. A galaxy that that redshift has never been seen before, and would be even older than SMACS 0723, which JWST imaged earlier. Astronomers think JWST is seeing that galaxy at 300 million years after the Big Bang. However, if Maisie’s galaxy is confirmed, it could have formed within just 290 million years after the Big Bang. This was during a period called the Epoch of Reionization when the first stars turned on as hydrogen began to be ionized, allowing the first light to shine through the Universe.