We talk about stellar mass and supermassive black holes. What are the limits? How massive can these things get?

Without the light pressure from nuclear fusion to hold back the mass of the star, the outer layers compress inward in an instant. The star dies, exploding violently as a supernova.

All that’s left behind is a black hole. They start around three times the mass of the Sun, and go up from there. The more a black hole feeds, the bigger it gets.

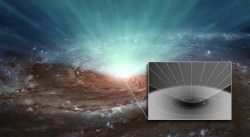

Terrifyingly, there’s no limit to much material a black hole can consume, if it’s given enough time. The most massive are ones found at the hearts of galaxies. These are the supermassive black holes, such as the 4.1 million mass nugget at the center of the Milky Way. Astronomers figured its mass by watching the movements of stars zipping around the center of the Milky Way, like comets going around the Sun.

There seems to be supermassive black holes at the heart of every galaxy we can find, and our Milky Way’s black hole is actually puny in comparison. Interstellar depicted a black hole with 100 million times the mass of the Sun. And we’re just getting started.

The giant elliptical galaxy M87 has a black hole with 6.2 billion times the mass of the Sun. How can astronomers possibly know that? They’ve spotted a jet of material 4,300 light-years long, blasting out of the center of M87 at relativistic speeds, and only black holes that massive generate jets like that.

Most recently, astronomers announced in the Journal Nature that they have found a black hole with about 12 billion times the mass of the Sun. The accretion disk here generates 429 trillion times more light than the Sun, and it shines clear across the Universe. We see the light from this region from when the Universe was only 6% into its current age.

Somehow this black hole went from zero to 12 billion times the mass of the Sun in about 875 million years. Which poses a tiny concern. Such as how in the dickens is it possible that a black hole could build up so much mass so quickly? Also, we’re seeing it 13 billion years ago. How big is it now? Currently, astronomers have no idea. I’m sure it’s fine. It’s fine right?

We’ve talked about how massive black holes can get, but what about the opposite question? How teeny tiny can a black hole be?

Astronomers figure there could be primordial black holes, black holes with the mass of a planet, or maybe an asteroid, or maybe a car… or maybe even less. There’s no method that could form them today, but it’s possible that uneven levels of density in the early Universe might have compressed matter into black holes.

Those black holes might still be out there, zipping around the Universe, occasionally running into stars, planets, and spacecraft and interstellar picnics. I’m sure it’s the stellar equivalent of smashing your shin on the edge of the coffee table.

Astronomers have never seen any evidence that they actually exist, so we’ll shrug this off and choose to pretend we shouldn’t be worrying too much. And so it turns out, black holes can get really, really, really massive. 12 billion times the mass of the Sun massive.

What part about black holes still make you confused? Suggest some topics for future episodes of the Guide to Space in the comments below.

And just as galaxies merge so do their black holes… for a while a galaxy can have two of the monsters…. http://articles.latimes.com/2002/nov/20/nation/na-blackhole20

Wouldn’t the smallest primordial black holes have evaporated by Hawking radiation by now?

We have all seen rogue stars hurtling through the galaxy with escape velocities. But is there any black holes hurtling through the galaxy with equally the same escape velocities?

BWS, if I’m sure about one thing than it’s this: the universe is stranger / has more than we can imagine.

For years the debate was “Are there planets out there?” – “Yes!” – “Ok… show me one!” And now we know the answer. For the planets. For the Black holes – well… has anyone seen ONE? No, we can’t but that doesn’t say there are none!!! But even if we know where to look… no chance 😉 So before one runs into a sun / planet / moon / spaceship….. and creates chaos, we can’t tell. 😉

“There’s no method that could form them [primordial black holes] today”

Quantum fluctuations can and do. But the vast majority are too tiny to notice and vanish instantly.

The odds of a black hole big enough to notice popping up are almost infinitesimally small. It has probably never happened in the visible universe since the big bang. But if you wait long enough it will.

Bob Berman, contributing editor with Astronomy magazine, contends that objects CAN escape from within the event horizon, and he does so with the backing of a Relativist with a Ph.D. no less.

Here’s a link laying out his conversation with myself and others; please get involved.

https://www.facebook.com/download/1684797785073267/Bob%20B%20Exiting%20from%20an%20event%20horizon.docx

Could supermassive black holes vacuum up all the barionic matter in the universe? Can their massive gravity overcome the expansion between

galaxies or galaxy groups?

Are supermassive black holes vacuuming up dark matter and dark energy as well as ordinary matter?

Can neutrinos zip through black holes the way they fly through the earth?

As photons, which are massless, can’t escape from within an event horizon, then neutrinos, which have (a tiny) mass, certainly (as I see it) couldn’t.

Thank you very much, Wayne. I didn’t know that neutrinos had any mass.

You’re welcome bonnieyes. Until relatively recently, they were thought to be massless.

With regard to your query as to whether black holes can overcome the universe’s expansion and consume all, the answer is no – the accelerating expansion seems to be pushing everything away from everything else, bar those bodies or groups of bodies sufficiently close enough together such that their mutual gravitational attraction does overcome the local expansion of spacetime.

As to whether they’re gobbling up dark matter and dark energy, we’ll need to find out just exactly what these mysterious phenomena are before we can address that question with confidence – as dark matter interacts with normal matter gravitationally, my guess is ‘yes’ for it; a less educated guess for dark energy would be ‘no’.

Does time stop inside a black hole? If so, where is the cutoff point? Does matter orbit the black hole essentially forever because time is so nearly

at a stop?

Those are good questions, bonnieyes. The short answer is that no one knows the answer to either question. The longer answer involves virtually all who knock their heads against this all the time. They involve the never never land between Einstein’s “classic” theory of relativity and quantum mechanics AND some future theory not yet even conceived.

If you delve deeply enough maybe YOU will be the one to reveal the answers to the rest of us.

Yes and no 🙂

As our friend Mr Einstein taught us, it’s all relative – what one person experiences can be seen differently by another.

If you were parked in a spaceship a safe distance from a black hole and watched another astronaut approach it, you’d see his movements begin to slow as he moved deeper into the gravitational field of the BH – from your perspective, his time is slowing, but to him, everything is humming along normally.

Just as he reached the event horizon, his time would appear to you to stop – you would forever see him sitting just on the verge of crossing the horizon.

He would, however, just sail freely across the horizon – with the nasty future and possible ‘spaghettification’ which that implies.

So while the phenomenon is real, it’s not inaccurate to say that it is in some ways just an illusion.

Oh, you explained this so well! Thanks!